From communicating complexity, to the risk of scaring audiences away, environmental journalists face no shortage of challenges

The modern journalist is much more than a writer and researcher. They must understand how to use social media to their advantage, be nimble with SEO, and compete with a never-ending stream of content, to name a few key competencies. Environmental reporters face these challenges and more as they report on one of today’s most pressing global issues—the ever-evolving climate crisis.

While the discussion of climate change in Canada is certainly not new (Environment and Climate Change Canada was created 50 years ago in 1971), climate anxiety seems to be steadily increasing. According to a 2022 article from The Journal of Climate Change and Health, about 78 percent of the young Canadians surveyed reported that climate change negatively affects their overall mental health. Additionally, approximately 56 percent of respondents said environmental concerns have left them feeling afraid, sad, anxious, and powerless.

These statistics are alarming and overwhelming, which is why journalists on today’s environmental beat have such a complex job.

Lack of Access to Information

As a climate and finance reporter for the National Observer, John Woodside understands the importance of providing the public with accurate and relevant environmental facts. Yet, one of the biggest barriers is a lack of easily accessible information.

To combat this, Woodside and his colleagues spend a significant amount of time filing access-to-information requests. While this process can be grueling, he says it’s essential to provide the public with knowledge they wouldn’t otherwise have access to.

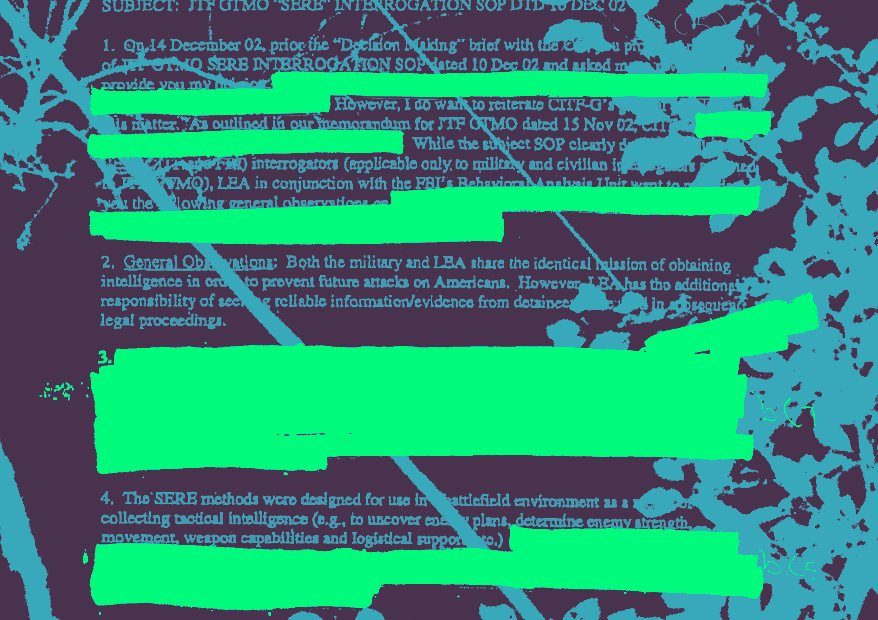

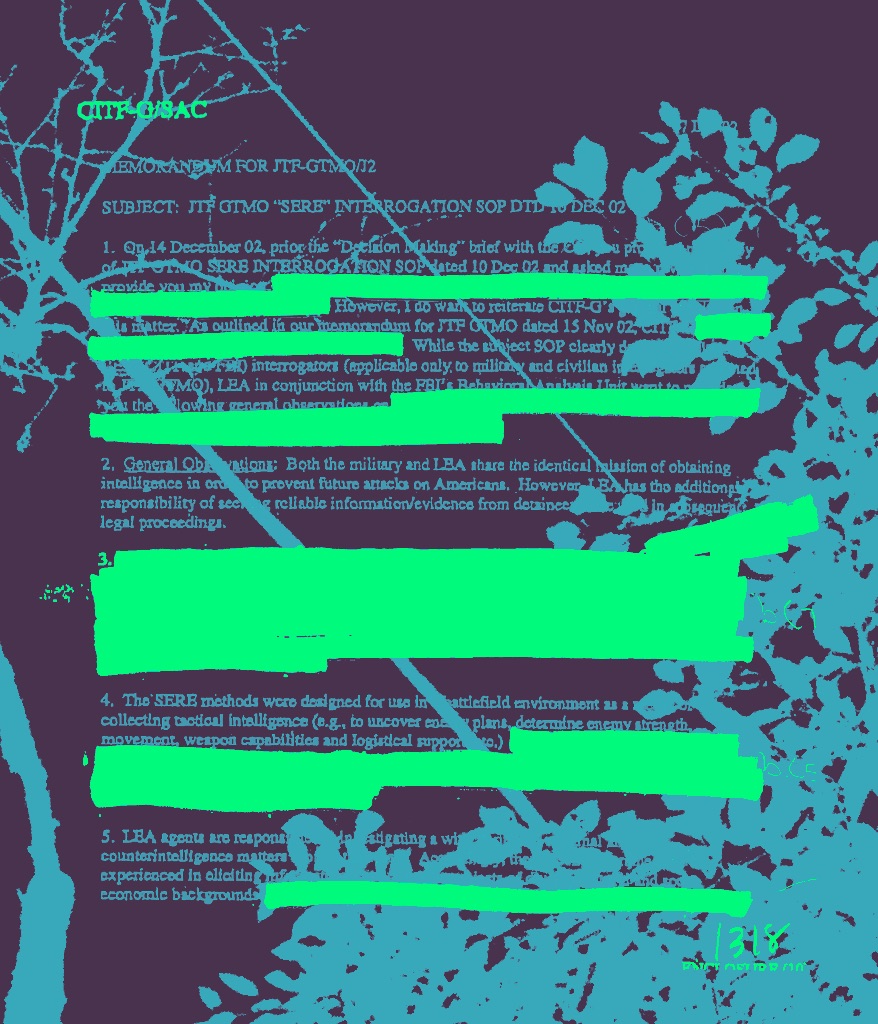

“A lot of the time these documents will be redacted,” says Woodside. “But there is usually a nugget of information that’s really useful that points to something.”

In June 2021, Woodside published an article about Big Oil’s future in hydrogen fuel which was the result of an access-to-information request. While researching the story, he discovered one line in a mostly redacted briefing note in which government officials wondered how to persuade financial institutions to invest in blue hydrogen, rather than green. According to Woodside, “green” hydrogen is made from renewables, which is largely emission-free, and “blue” hydrogen is made from fossil fuels, which is less climate-friendly.

“That gives us clues about what the federal government is doing here,” he says. “This isn’t something [the government] would ever admit if you just ask them directly. But when you see it in government documents, through access to information, you can start to piece together what’s actually going on.”

Clear Communication

Carl Meyer, the climate investigations reporter at The Narwhal, says that sorting through complex scientific data can be overwhelming, especially when he has to repackage and communicate the latest environmental news to the public. He also admits that although he’s covered climate-related stories for several years, he still doesn’t see himself as an expert on the topic and is constantly looking for new ways to strengthen his reporting.

“You can very easily and quickly get lost in this huge, broad, abstract concept of climate change and get very in the clouds about it and away from the real issues that are happening to people,” says Meyer.

While it can be tough to communicate these subjects on a level the public will understand, Meyer adds that people are often interested in environmental news because they see how climate-related events affect their daily lives. But overwhelming audiences with too much intense material can also have a negative result.

“You have to include hope, because we’re hit over the head with this idea that the planet is dying…and that doomerism leads to paralysis,” he says.

“Flight or Fight Syndrome”

Meyer is talking about “climate fatigue”—an apathetic reaction to constantly hearing about all the upsetting realities of climate news. This is a serious problem for climate reporters.

Ian Hanington, senior writer and editor at the David Suzuki Foundation, has encountered this problem countless times since he started reporting on the environment in 1989. “To convey those issues in a short, succinct way that makes sense, but still engages people, and still encourages them to get involved in some way, has always been a challenge,” he says.

“The main challenge is finding that balance between not wanting to scare people so that they run and hide. [It’s] the whole flight or fight syndrome.”

Intense content and resulting climate fatigue, can cause climate reporters to struggle with audience retention, notes Sierra Bien, a content editor at The Globe and Mail and author of its weekly climate newsletter, Globe Climate.

Every week, Bien highlights a collection of recently published environmental stories for the newsletter. While several factors determine which stories she chooses, keeping the audience’s perspective in mind is a priority for her.

“I definitely think that having the [right] mix of stories is so important because you don’t want to just always be dumping horrible news on your readers,” she says. “I think people are craving connection to the world around them and the environment and the planet. And I think that we can achieve that.”

Although Bien says she recognizes the merits of positive environmental journalism and tries to highlight uplifting stories wherever possible, she also explains that it’s imperative to be completely truthful with readers, even when the realities of the news aren’t so cheery.

“There’s no silver bullet,” says Bien. “I think, more than anything, it’s just so important for people to inform themselves as much as they can.”

Though climate reporters face unique obstacles, John Woodside says the job is rewarding nonetheless. He’s especially grateful to see both mainstream and independent media outlets supporting environmental journalism.

“I think climate reporting is one of the most important things happening in journalism right now,” says Woodside. “It’s not just the climate-focused publications that are doing it anymore – really everyone is taking a climate lens to various degrees.”

About the author

Stephanie is in her fourth-year of TMU’s undergraduate journalism program and has an immense love for long-form magazine stories! She’s also the features editor for TMU’s independent student newspaper, The Eyeopener, and the co-editor-in-chief of New Wave Magazine. She’s immensely grateful for the opportunity to be part of the Review’s 2022-23 masthead and is excited to continue working in the journalism and magazine industry after she graduates!