The Review of Journalism strives to create a workplace and publication that reflects the diversity of both our readers and the stories we tell. As a new measure in 2022, we have chosen to publish an anonymous breakdown of the race, gender, sexuality, and disability representation of our staff.

The Review staff consists of a mix of undergraduate and graduate students at X University, who fill a variety of editorial roles. It also includes our instructors, teaching assistant, and handling editors, plus a number of additional masthead roles such as copy editing consultants and art directors. All told, a total of 44 individuals were surveyed. Findings from the survey are presented below, alongside statistics from two major media organizations and X University itself. These external data points are included to illustrate how the Review’s data differs from that of other industry organizations.

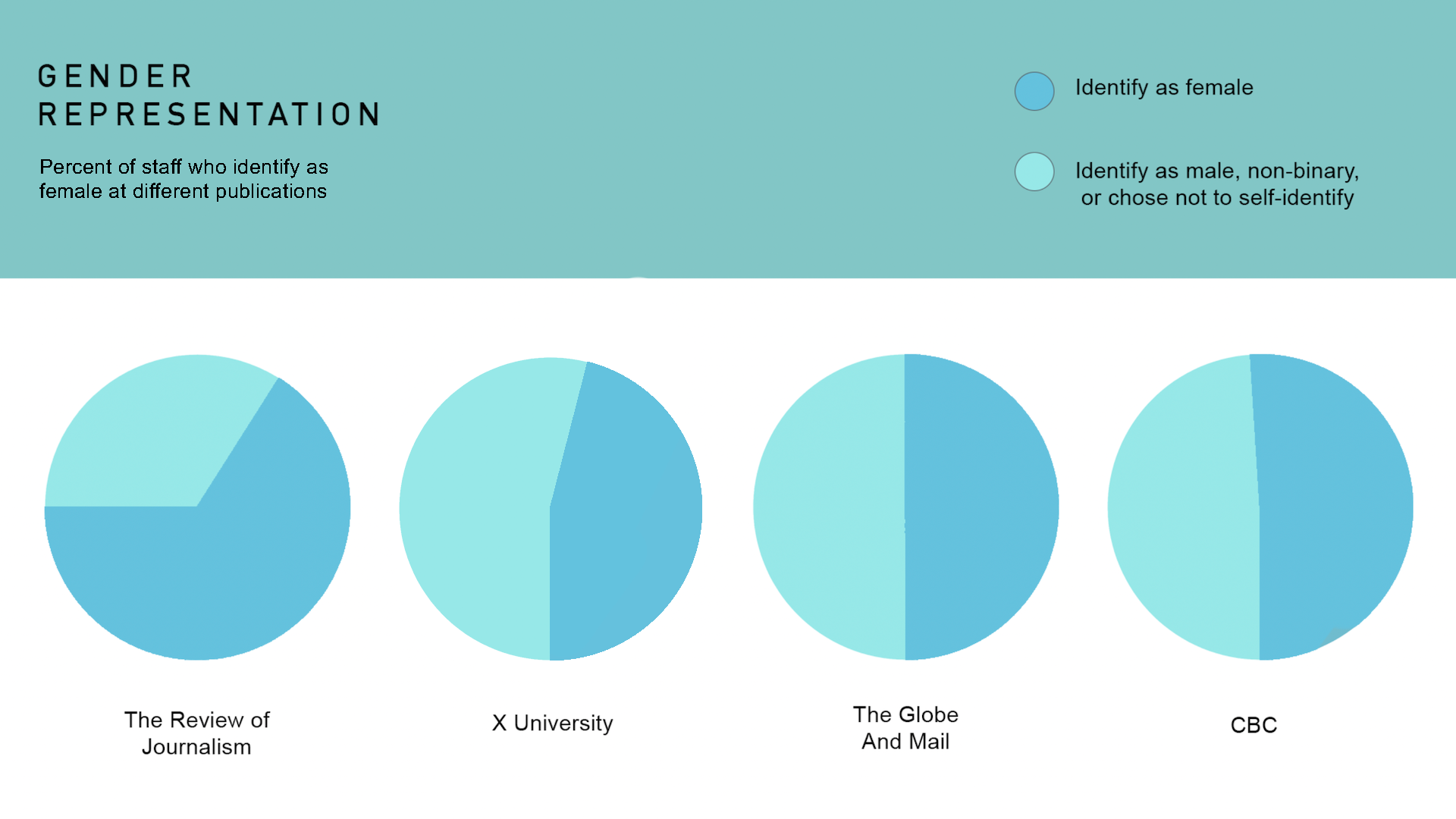

Sixty-six percent of the Review’s staff identify as female, while 29 percent identify as male, and five percent identify as non-binary. This rate of representation is significantly higher than the proportion that women represent at the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, The Globe and Mail or X University itself (49 percent, 50 percent, and 54 percent, respectively).

It is also worth noting that these organizations are structured differently and collect data with different practices from the Review’s. We include them here because we feel they are the closest possible metric by which readers can understand the state of diversity representation in Canadian newsrooms, as well as our own university.

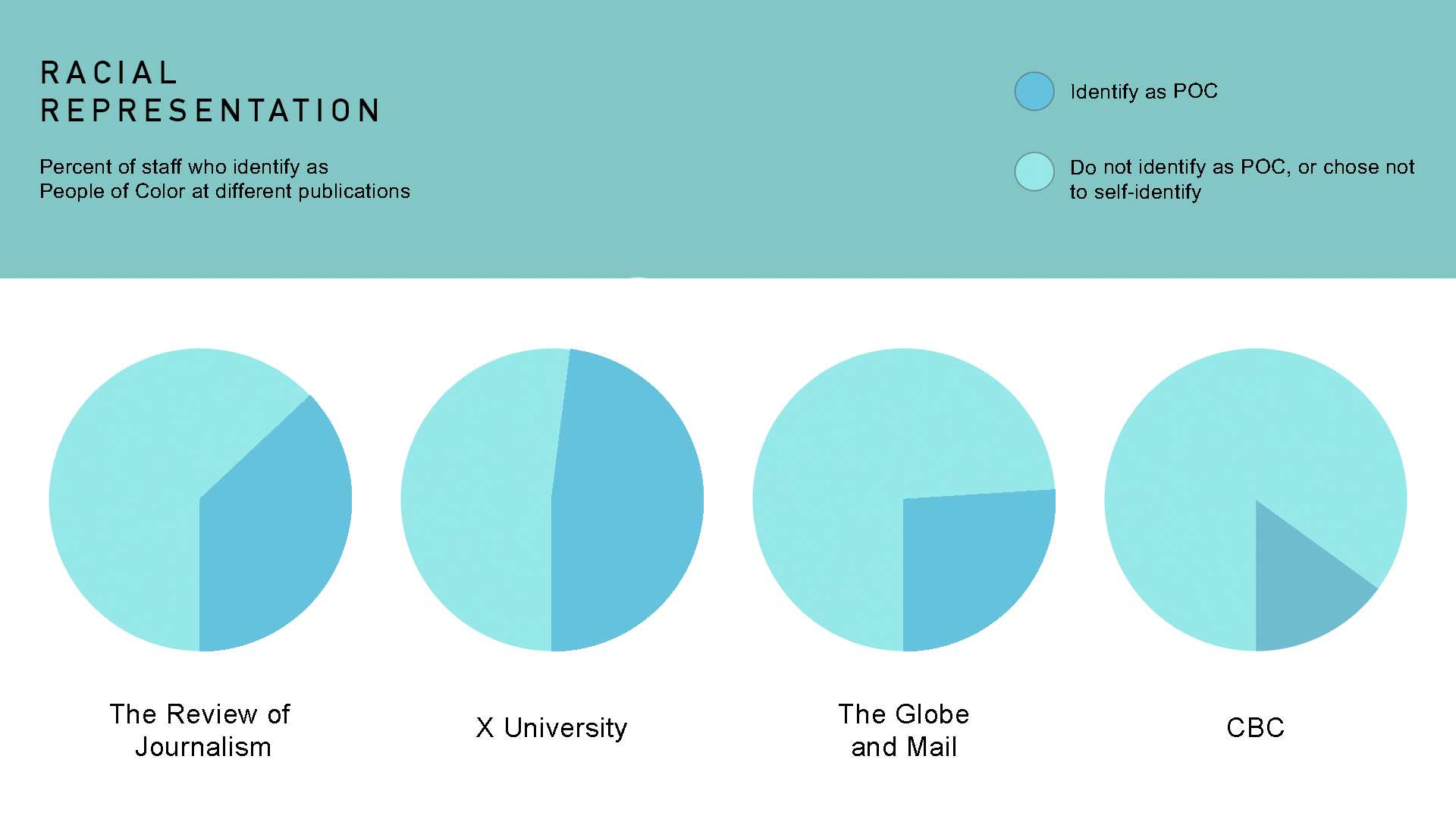

Thirty-seven percent of the Review’s staff self-identify as people of colour. This is significantly different from statistics at X University, 48 percent, and The Globe and Mail, 26 percent. It is worth noting that the Review’s masthead is a fairly small sample size, especially compared to X University with a population of over 40,000. Additionally, the percentage of Review staff who self-identify as people of colour is significantly higher than the 15 percent of CBC employees classified as “visible minorities,” a term defined by Canada’s Employment Equity Act as “persons, other than Aboriginal peoples, who are non-Caucasian in race or non-white in colour”. Despite this high proportion, a further breakdown of the minorities represented reveals some glaring disparities.

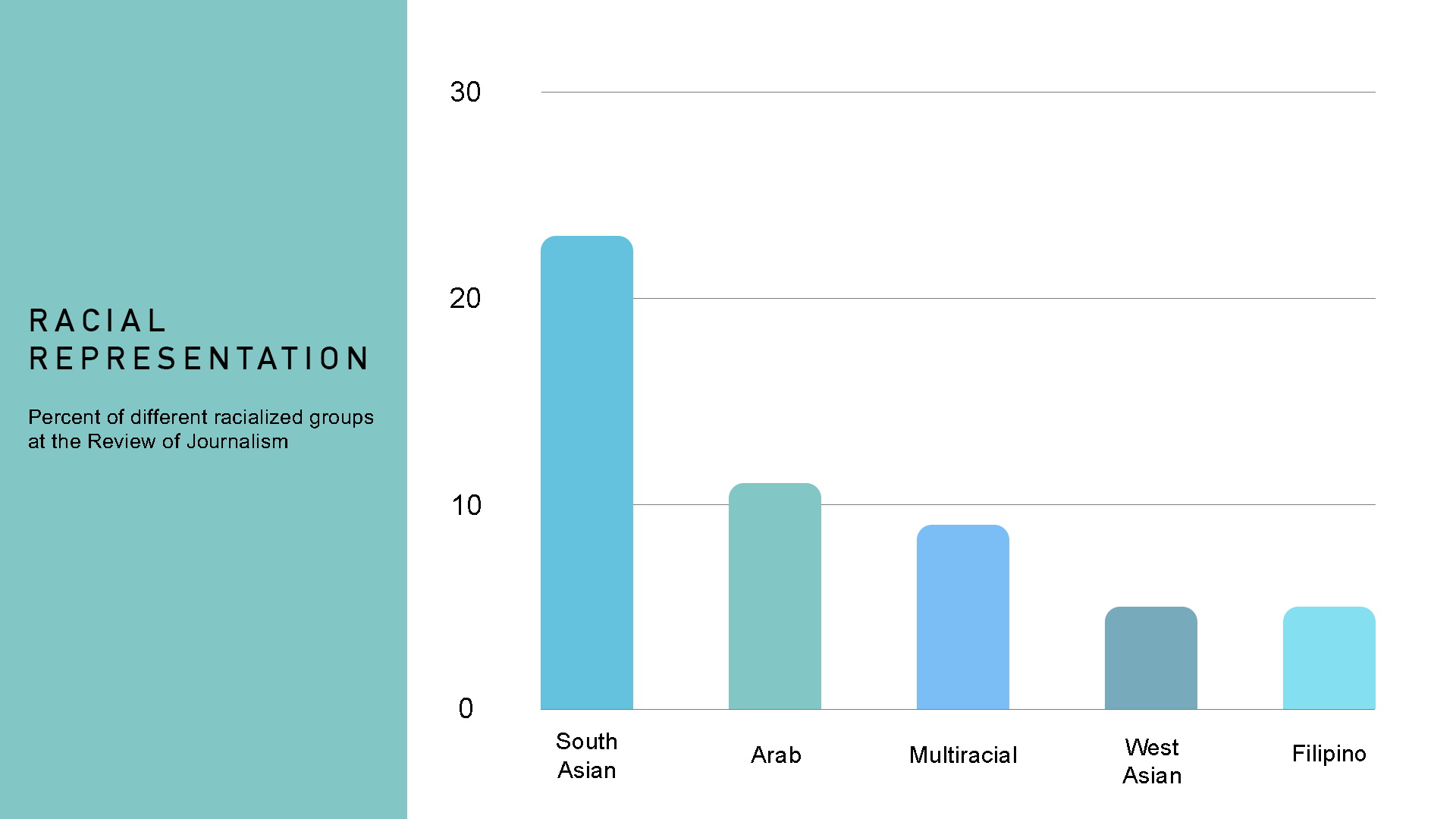

Twenty-three percent of the Review’s staff self-identify as South Asian, 11 percent as Arab, nine percent as multiracial, five percent as West Asian, and another five percent as Filipino. This variation represents a diverse range of peoples but leaves the Review at a unique disadvantage when reporting on issues important to Black, Indigenous, or East Asian communities.

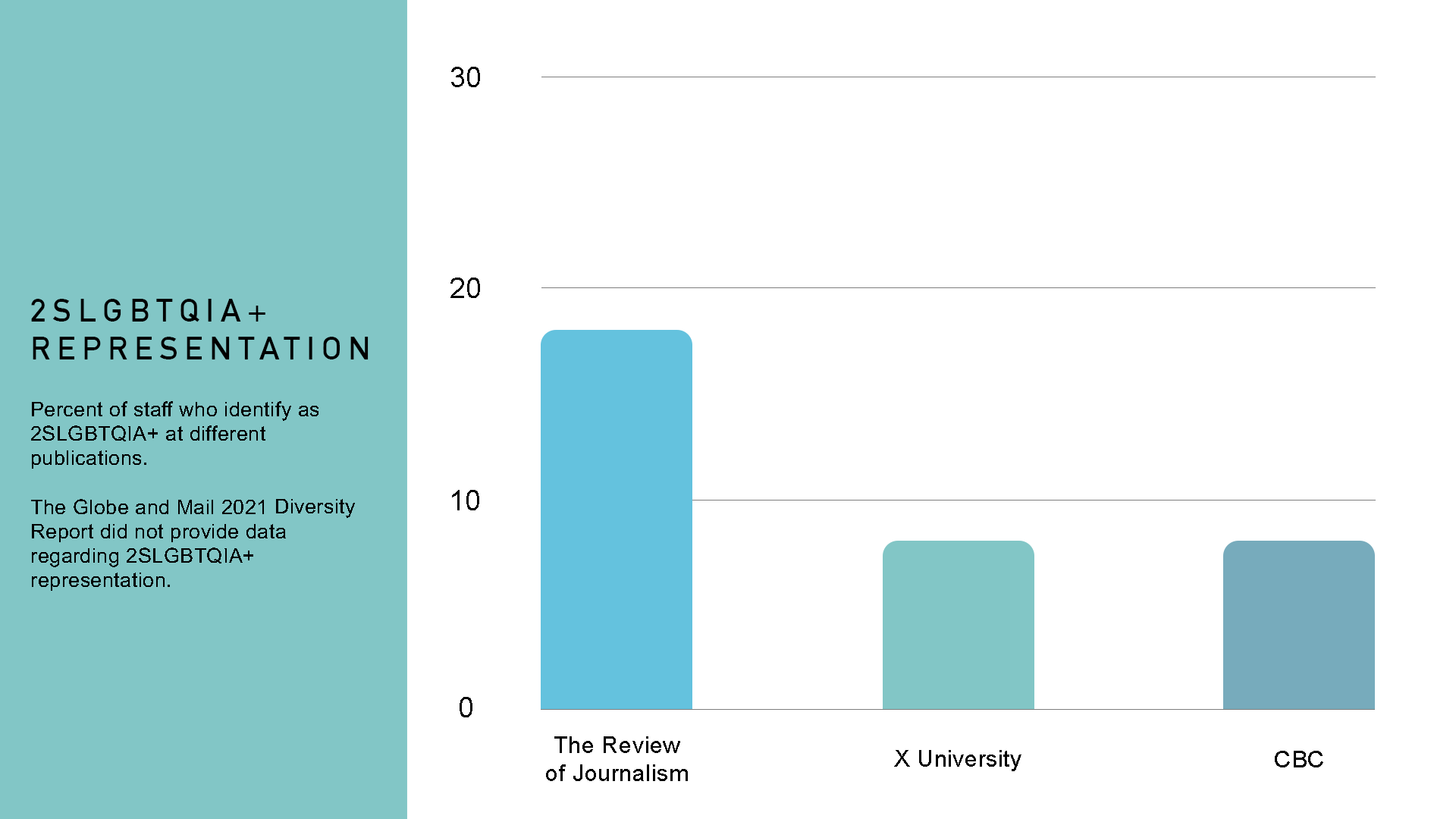

Eighteen percent of the Review’s staff self-identify as 2SLGBTQIA+, an increase over the eight percent present at both X University and CBC, and certainly higher than the four percent rate of Canada’s general population aged 15 and older. A further breakdown of which different members of the queer community compose the Review’s masthead (seven percent bisexual, seven percent lesbian, five percent non-binary, five percent queer, five percent trans, and two percent gay) yields no further insights beyond assurance that a wide range of the community is represented.

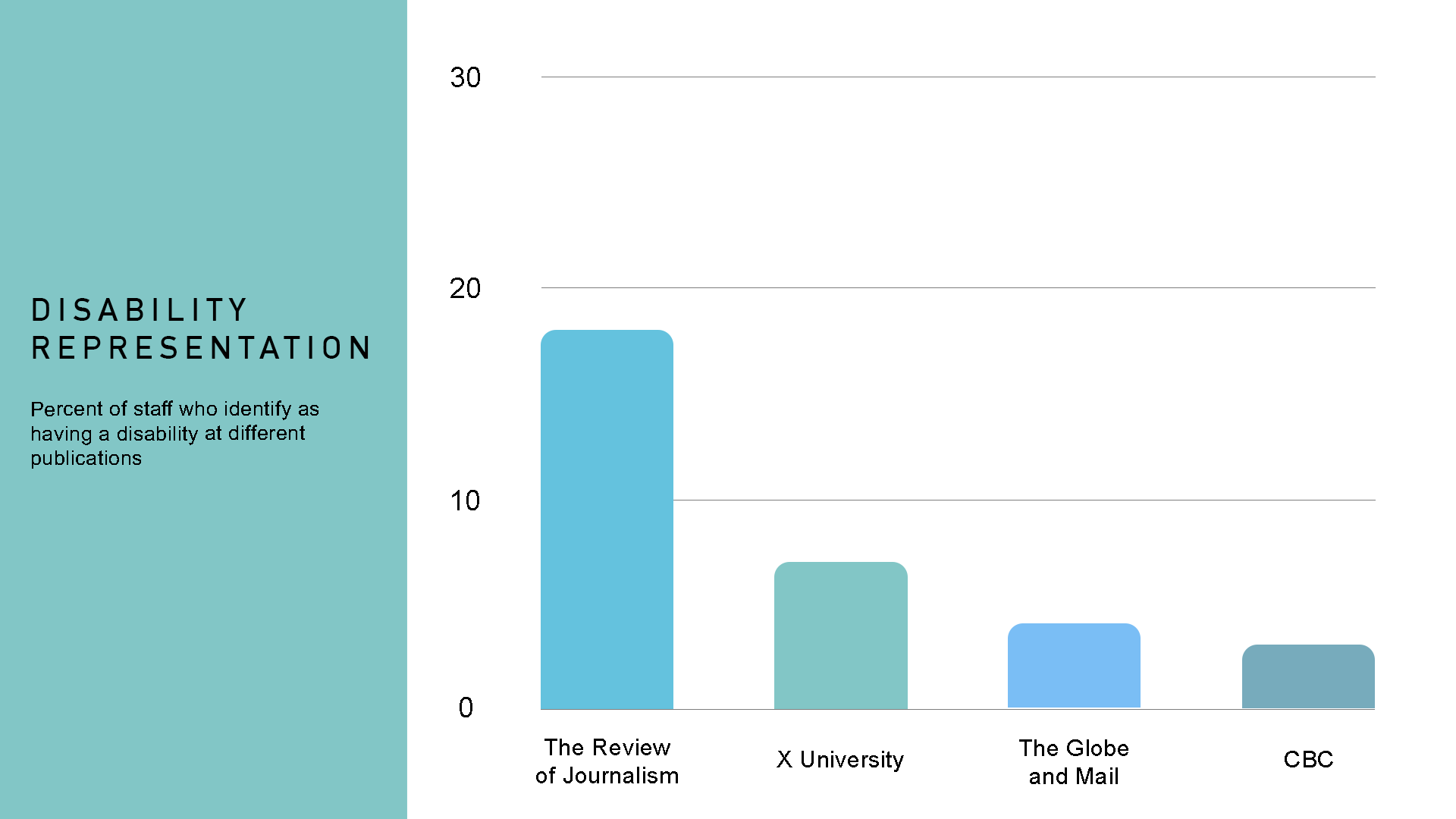

Eighteen percent of the Review’s staff self-identify as having a disability, with 16 percent naming a mental health-related disability. This is roughly in line with the 22 percent of Canada’s population that identify as having disabilities, but it leaves the editorial team with a limited perspective on physical disabilities.

While the data as outlined above clearly shows where the Review is lacking in specific voices and viewpoints, it does not mean that we will avoid covering stories that are outside of our wheelhouse. The masthead at the Review of Journalism is lacking Black and Indigenous representation, as well as persons with physical disabilities. In acknowledging these gaps, we make a commitment to actively combat the historical narratives that have misrepresented communities in the past and present.

The rest of our stories online and in print will be deeply personal, as any good writing is, but the numbers shared above are intentionally impersonal. They don’t define who any of us are—but now that we’ve shared them, we can get to the stories, facts, and ideals that do.