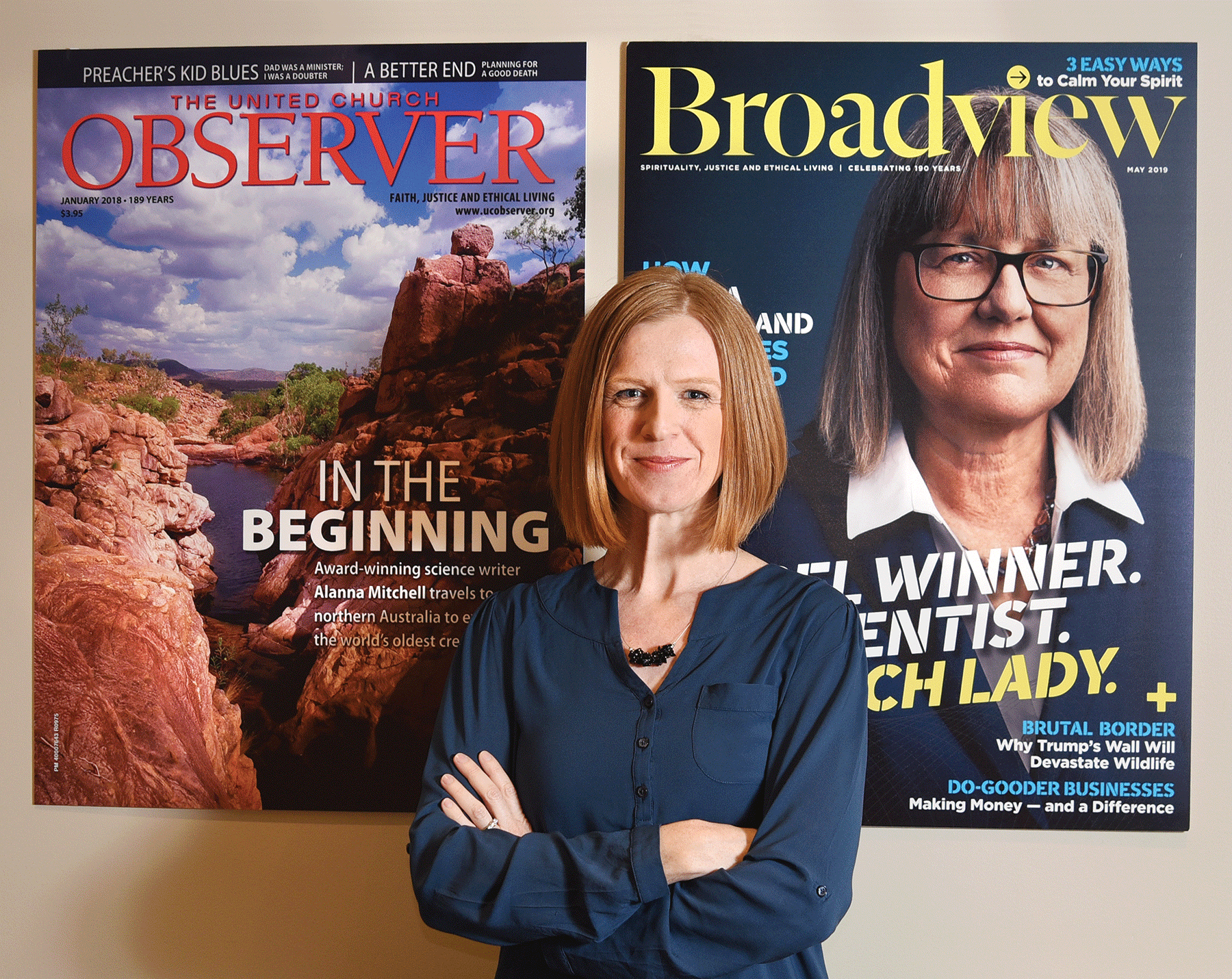

The inside story of how The United Church Observer turned itself into Broadview, a re-invention to expand the publication’s audience and mission

[su_dropcap style=”simple” size=”10″]A[/su_dropcap]t the Presse Internationale Magazine Super Store in Toronto’s eclectic Annex neighbourhood, a vast assortment of publications from around the world line the crowded shelves. The shop stocks countless Canadian and international titles. Vogue Arabia is displayed in the fashion section. France’s Le Monde diplomatique is stacked among an array of newspapers from various continents. Beside each other are the literary and politics sections, where celebrated Canadian publications—The Walrus, Maisonneuve, Alberta Views, Newfoundland and Labrador’s NQ magazine—are stocked beside The New York Review of Books and the U.K.’s The Spectator. The shop’s worldly assemblage of publications, each representing different identities, beliefs, and viewpoints, is comforting; inviting, even. Within the multitudes, there is a sense of inclusivity. A few titles down from The Walrus and right beside Maisonneuve, the shop owners have also stocked North America’s oldest continuously-published publication, a religious magazine, its origins rooted in serving the traditions of the United Church of Canada.

Just east of Presse Internationale are two United Churches. Three blocks away is Trinity-St. Paul’s United Church and Centre for Faith, Justice and the Arts, an amalgamation of what was previously two separate churches, combined due to the shrinking population of worshippers at both. Another six blocks east from Presse Internationale is the Bloor Street United Church, a norman-gothic building that sits at the corner of Huron and Bloor Streets. The 134-year-old building is weathered now. The old stone is dirty, and the roof has oxidized. Inside the hallowed hallways of the church, towards the building’s offices, layers of duck-egg blue paint are peeling.

The Bloor Street United Church is not only a place of worship for Christians. Jewish congregations also use the space for religious activity, on Saturdays. The decline of United Church members has led to the shuttering of thousands of United Churches across Canada at a rate of one per week. The Bloor Street United Church has adapted by offering its venues to serve other religions and denominations. Today, this particular space is shared with Toronto’s City Shul, a reform synagogue.

Back inside Presse Internationale, the magazine formerly known as The United Church Observer looks more like a modern general interest periodical with a healthy creative budget than a Christian publication, albeit a progressive one. Underneath the magazine’s title, in words an eighth of the size, is its tagline: “Spirituality, justice and ethical living.” A photograph of two teenage Maasai girls in Southern Kenya is on the front cover. The headline reads, “New Traditions: How Women and Girls Affected by Female Genital Mutilation Are Taking Charge of their Future.” Cover lines include “Boot Camp for Mystics: Training the Soul for Social Good,” and “The Demon Next Door: TV Comedies Reimagine Evil.”

This glossy publication has 191 years of history. But much like the United Church’s own tactics toward keeping its spirit alive and congregation engaged, the magazine, too, has undergone a rebrand. In April 2019, with a new vision to attract readers from beyond its 65–75-year-old religious demographic, the magazine was renamed Broadview.

[su_dropcap style=”simple” size=”10″]I[/su_dropcap]n 1986, the Observer, as the publication was formerly known, incorporated and became independent from the United Church. (The magazine receives only six percent of its total revenue from the church.) Its management established a board of directors that included a range of perspectives, and gave the United Church the ability to choose 30 percent of board members. Over the years, the magazine’s commitment to editorial independence has been exemplified by the stories run within its pages. A six-page feature on accepting gay and lesbian ministers into the United Church ministry, for example, ran in 1988. the Observer also covered stories about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in the 1970s, and animal testing practices in 1988. In 2013, the magazine published an article about the extinction of a small water bird in Argentina. That piece won a National Magazine Award. The publication has continued to examine difficult questions that surround church life, subjects sometimes addressed in United Church sermons—such as challenges of faith, and Christianity’s role in the colonization of Indigenous communities.

“We started covering residential schools long before residential schools were even a blip on the mainstream radar,” says David Wilson, who became editor of the Observer in 2006. In a 2004 feature, called “An Indigenous mother searches for answers on B.C.’s Highway of Tears,” he wrote about Ramona Wilson, a teen who went missing, and was found to have been murdered, in Northwestern British Columbia. In the run-up to the 1988 presidential election in the United States, he covered the rise of the Christian right in an article called “Piety and Politics, U.S.A.,” which was nominated for a National Magazine Award.

[su_dropcap style=”simple” size=”10″]I[/su_dropcap]n 2007, the Observer underwent a complete stylistic redesign, a transformation that notably swapped newsprint for glossy paper. Wilson wanted to make sure that this “church magazine seems more like, for lack of a better word, like a real magazine.”

Wilson’s goal was for the Observer to exceed the expectations of typical church magazines, which often skew toward promotion of religious institutions, from which they usually receive funding. “They tend to be preachy,” he says. “They don’t emphasize the fundamentals of magazine publishing—good layout, good images. And they don’t make an effort to speak beyond their own constituency.” Ultimately, Wilson wanted to appeal to an audience of potential churchgoers, but also to those who shared similar values without necessarily being religious.

By 2017, says Wilson, the board of directors were aware that “it was time to reinvent my invention,” as the magazine continued to lose readers. It had been a decade since Wilson’s rebrand. After 30 years at the magazine, Wilson knew he wasn’t the right person to take the title into the next phase of its history. He was ready to retire.

Before he left, Wilson hired magazine publishing consultant Sharon McAuley to assess the current health of the organization and forecast what may happen if they continued with the status quo, which involved looking at the publication’s financial statements and circulation numbers. McAuley was impressed that the board of directors were ahead of the curve and in a strong financial position. Still, they wanted to address the Observer’s attrition. “I think they were genuinely concerned because the Presbyterian Record had just closed down…and so they were thinking that it’s not the time to be sitting back and just letting things happen,” says McAuley.

McAuley examined the Observer’s content, and she was also impressed by its progressive social justice features. In 2017, a story called “A Tale of Two Cancers” chronicled the diagnosis of two sisters with breast cancer, one living in Toronto, the other near Los Angeles. Due to the inaccessibility of medical care in the United States, the sisters’ experiences were vastly different. (Senator Bernie Sanders used the research from the Observer’s story in a 2017 video about healthcare in America.) When the story went viral, McAuley could see that the magazine’s stories had the potential to engage an audience beyond the traditional church-affiliated reader.

[su_quote cite=”David Wilson, former editor The United Church Observer”]We started covering residential schools long before residential schools were even a blip on the mainstream radar [/su_quote]

In January 2017, McAuley presented her initial assessment to the board and suggested possible options to reach a broader audience including expanding to the United States and spending more money on marketing. “They were intrigued by this idea that there could be potential readership beyond the United Church pews of people who share the same values,” says McAuley.

[su_dropcap style=”simple” size=”10″]B[/su_dropcap]roadview’s former office was in an old Annex home owned by the Bloor Street United Church. As adjustments at the core of the magazine were beginning to take shape, the editors moved to a new space across town. The office relocation was intended as a gesture of journalistic independence—and came with central air conditioning. Today, the new Broadview office is stationed within a vibrant cluster of bars, bakeries, a music venue and local shops on the Danforth Avenue strip, a block away from Broadview Avenue. Jocelyn Bell was appointed editor and publisher in 2018. (Following a yearlong overhaul, the publication was renamed in April 2019.) It was as though she was destined for the job.

Bell is the daughter of two retired ministers, and was even a young contributor to the magazine. Donna Sinclair, a former writer for the Observer, found five-year-old Bell through Bell’s parents’ connections within the United Church. She asked her to read a children’s book called Pettranella, about a girl who immigrated to the United States from Eastern Europe. Bell’s quotes about the book appeared in the December 1981 issue.

After that early childhood cameo, Bell wouldn’t write for the Observer until she was an undergraduate at Queen’s University. Bell’s mother suggested she contact editor Muriel Duncan, as Bell was looking to explore the option as a career, in addition to writing for the Queen’s University newspaper. “They just felt like real journalism and not fluff pieces,” Bell says of the stories she wrote during university. After completing her Bachelor of Applied Arts at Ryerson University, Bell worked at The Hamilton Spectator and at World Vision’s Childview magazine. But the Observer found her again, in 2006. This time, Sinclair, her handling editor, told Bell that the magazine was hiring an associate editor. At first, Bell hesitated. “When your parents are ministers and you’re trying to define yourself… Did I really want to go work at the church magazine?” But Bell knew the publication was about more than just the church. And she had a desire to pursue social justice issues with journalism. In August 2008, she told Wilson she wanted more responsibility. A month later, she became managing editor.

Inside Bell’s office, a stack of Broadview issues sit on her desk alongside papers and stationery. A calendar is displayed on her computer and past and future mockup covers are tacked to the beige office walls. Bold yellows, bright reds, and large typefaces are on covers that feature climate activist Greta Thunberg, a tent under Aurora borealis for their “10 Spiritual Road Trips,” and an image of Nobel Prize winner, Donna Strickland.

“Circulation decline has been ongoing since the 1960s,” says Bell. “You can get tighter and leaner in lots of ways. But at what point is it going to be exponential?” D.B. Scott, a Broadview board member and the author of a blog called Canadian Magazines, says casting content to a new Observer audience was vital. “They had to stop the bleeding, essentially,” says Scott. “The decline of the Observer had to be stanched, it had to be stopped and then reversed.”

Bell says that Wilson’s leadership expanded the magazine’s editorial scope, distinguishing it from other religious publications. “Does every story have to be about the United Church of Canada? No, it has to be interesting to people in the United Church of Canada. So it can be about all kinds of different global issues and things that don’t necessarily relate to the church,” she says. She adds that Wilson’s vision “paved the way for where we are now.”

Scott says Broadview fills a void left by other religious publications. Magazines such as the Salvation Army’s Salvationist or the Anglican Journal continue to operate as “very much a house organ,” reporting on births, deaths, appointments, and news relating to the clergy and congregation. He says, “If you look at something like the Anglican Journal, well, it’s pretty plain vanilla compared to what Broadview is trying to do.”

Based on McAuley’s 2017 assessment, the board agreed that the Observer’s name might be limiting its audience. McAuley identified that the name was a “point of confusion,” because it suggested that the publication was an “organ of the church,” as Scott also noted. The board decided to investigate what their new market and potential new name could be. They wanted to test their hypothesis that the branding and packaging were “obstacles preventing people from looking at the publication and discovering all the great articles,” says McAuley.

Next, the board figured out the best way to proceed in completing the rebrand. Bell says they knew their prospective audience included people who read magazines and those who considered themselves spiritual in some “very vague, biggest picture way.” They knew their readers were likely to be liberal-leaning, on board with LGBTQ2+ and women’s rights, and supportive of Indigenous reconciliation. Those parameters established the format for a survey conducted by Strategic Content Labs, who tested the potential of a new audience.

The survey suggested that with a new name, the magazine’s target demographic could be much younger than its current audience of readers, aged 65-plus. The survey also confirmed that the magazine’s readers would be interested in a publication that had some focus on the United Church, but which was more focused on spirituality and social justice. Its new target demographic would be aged 50–64. Its second largest age target would be 18–34. There was room to capture more readers from urban communities and more readers who were men. (In recent years, the magazine’s subscribers were mostly women.)

Although the demographic groups differed, they had one thing in common: Shared values. This was a great relief for Bell. “It’s hard to make a magazine if you’re thinking, ‘let’s do something for the older women and something for young men in cities,’” she says. Bell imagined these groups as a Venn diagram. “Both scored really high for being lifelong learners, interested in equality across gender, race, and LGBTQ, giving to charity, caring about the environment, loving to learn from other cultures, learn new things, and being challenged,” she says.

Ultimately, their market research showed that rebranding the magazine with a new name, but running similar content, could diversify its audience. McAuley says that the ethical, social justice, and spirituality-focused articles “didn’t have to change, they just needed to be unlocked.”

[su_dropcap style=”simple” size=”10″]K[/su_dropcap]risty Woudstra, the features editor at Broadview, was working as a freelance journalist when she was approached by

Bell to help rebrand Broadview’s new website and magazine. Shortly prior, Woudstra had written a story for the Observer about sexual abuse within the Jehovah’s Witness religion. When she pitched the story, Woudstra wasn’t sure if the idea was suitable for a church-affiliated publication. But Bell was interested.

Woudstra was Bell’s former boss at Childview magazine, but left to become director of public relations at the World Wildlife Fund. Eventually, she realized she wanted to get back into journalism. With the decline of print publications prompting an industry-wide push to go digital, Woudstra joined Today’s Parent as their website editor and redesigned their website. She later joined HuffPost Canada as editor of the parents’ section.

“She presented me with this Venn diagram,” says Woudstra of Bell’s initial invitation. At the centre was the audience. “Very rarely have I seen that, where the readers come first.”

“We don’t want to be elitist. We don’t want to be lofty. We want to be approachable. We want to be diverse, and we want to be surprising, and engaging and compelling, but also have moments of laughter and fun,” says Woudstra.

[su_quote cite=”Zahra Khozema”]This was the first time I saw a faith-based magazine be so openminded to different topics, especially LGBTQ2+ issues, the environment, and even other religions [/su_quote]

The values that guide Broadview’s editorial mandate—covering ethical living, social justice, and spirituality, alongside United Church news, and a commitment to longform journalism “of the best calibre that we can muster,” says Bell—carried over from the Observer, and have attracted writers from various life backgrounds. Alanna Mitchell, an award-winning science journalist and the author of Sea Sick: The Global Ocean in Crisis, has written for the Observer for several years. Mitchell describes her experience with the magazine as “extremely inventive and very open.” She says she’s never viewed it as a religious publication, and that she’s always been free to report on what interests her.

Mitchell, whose piece about Nobel Prize-winning physicist Donna Strickland was Broadview’s first cover story, adds, “I’m fascinated with how the human mind processes science and faith…[the Observer] just felt like a place I could do that kind of writing, and that’s one of the things they felt they had a readership for.”

[su_dropcap style=”simple” size=”10″]Z[/su_dropcap]ahra Khozema was never a member of the United Church. She identifies as Dawoodi Bohra, a small sect within the branch of Shia Islam. When she walked into the first day of her internship at Broadview, she says she quickly felt comfortable. Khozema pursued the internship because she was interested in the ethical living and social justice features that the Observer had become known for.

A story by Khozema, called “I underwent FGM. It doesn’t define me,” about female genital mutilation, or khatna as it is called in Lisaan ud-Da’wat, ran on the March cover of Broadview. She says her editors were supportive when she pitched it. In the story, she writes:

I’ve tried to write this piece for years but trashed the document each time I started. I feared people viewing our sect in a negative light, and more so, being ousted from my community. But I’m doing this now because I don’t think khatna defines me or other Bohra women who’ve gone through the procedure.

Khozema says she felt a sense of safety writing the piece for Broadview because “it’s a smaller publication,” and describes the process as “therapeutic.” She says they give all of their stories a lot of care, but describes the editors as going “above and beyond” for her story. Before it was published online, Khozema recalls Bell checking in to make sure she was feeling sound ahead of its release.

Soon into her internship, Khozema realized that, unlike herself, the rest of the editorial team was familiar with the United Church. She says her colleagues were welcoming as she learned more about the church’s history and politics. “This was the first time I saw a faith-based magazine be so open-minded to different topics, especially LGBTQ2+ issues, the environment, and even other religions,” she says. Khozema also launched Broadview’s Instagram platform. “They’re trying to grow their audience,” she says.

[su_dropcap style=”simple” size=”10″]J[/su_dropcap]ohn Longhurst, a freelance religion columnist and reporter for the Winnipeg Free Press, says Broadview’s rebrand has “taken away the main barrier to someone who might not belong to the church.”

He points to the growing demographic of Canadians who do not identify with any religious groups—a group colloquially termed “nones,” meaning those who respond “none” when asked about their religious affiliation on the Canadian census. Longhurst says that despite a lack of denominational loyalty, many people still identify as spiritual, and would have an interest in a publication that targets subjects within Broadview’s pillars.

According to the spring 2018 Global Attitudes survey, conducted by the Pew Research Center, 55 percent of Canadians identify as Christians, but 30 percent of Canadians identify as unaffiliated. The survey also points to the growth of other religions in Canada, including Islam, Hinduism, Sikhism, Judaism, and Buddhism, which the survey attributes to immigration.

In 2017, the Angus Reid Institute, a not-for-profit foundation that conducts independent research, created a study known as a “spectrum of spirituality.” The study’s 2019 data shows that spiritually-committed individuals have been on the decline since 2017, dropping from 22 to 16 percent of survey participants. Those who identify as spiritually uncertain have increased from 30 to 41 percent in 2019.

“Broadview, knowing that lots of Canadians are spiritual although not religious, might well tap into a really good market for looking at these topics from that perspective,” says Longhurst. He notes that issues covered by Broadview—climate change, racism, and Indigeneity, for example—are also covered by the mainstream Canadian media. But these topics, he says, are explored by Broadview through “a slightly different perspective, which would incorporate spirituality more.”

Though religious affiliation is in decline, elsewhere in Canadian media, other religious outlets are keeping the faith, with Broadview as a guiding light.

[su_dropcap style=”simple” size=”10″]I[/su_dropcap]n December 2019, CBC Radio’s Tapestry, a 25-year-old weekly program that covers topics relating to religion, psychology, and spirituality, featured a segment with writer Anne Thériault. She had written for Broadview about unique mental health programs in Geel, Belgium. She mentions in the segment: “I was doing all my research, already starting to draft a piece. My editor emailed me and said, ‘Have you ever thought about actually going to Geel?’” Thériault—who had a horrible fear of flying—was terrified when Broadview offered to pay for the trip. Despite her fears, she made the flight, carrying the prayer card of St. Dymphna, the patron saint of mental illness. On the segment, Thériault shares her personal story—also penned in The Walrus—about how the prayer card helped alleviate her fear. Mary Hynes, host of Tapestry, says this segment revealed an affinity between Broadview and Tapestry. “Our scenes are so similar,” she says.

Hynes was also touched by another Broadview story, the December 2019 cover story, written by Pieta Woolley about her disenchantment toward Christmas. Hynes saved the piece, wanting to remember a passage that spoke to her:

I’m really good at feeling miserable and cynical. Joy often eludes me, especially at Christmas. Lamenting species loss, sneering at container shipping—this is my area of expertise. What I fail at is leaning into hope, wondering at hope, making way for hope.

“That one paragraph stopped me in my tracks,” says Hynes. “At Tapestry, this is what we call ‘my real person talking to your real person.’ It was just so disarming and so honest. You feel a kinship with the writer. It’s so clearly readable, but it’s not there for clickbait.”

Hynes says there is more of an appetite among Canadians to think and hear about psychology, philosophy, sociology, and spirituality. “It just gives you a much richer palette,” she says. Hynes recalls meeting with Bell just before the Observer rebrand. She says it was clear that Bell had lots of ideas for how to honour the magazine’s history while “broadening the magazine’s outlook to bring in things that would not have fit into a more conventionally capital-R religion magazine.”

Since Hynes became the host of Tapestry in 2003, the show has similarly gone through changes to examine spirituality that does not necessarily take place in the church. “The eternal questions never go away,” she says.

Still, there are some skeptics. In April 2018, Douglas Todd, a migration, diversity, and spirituality writer at the Vancouver Sun, wrote that the United Church is a denomination that “increasingly lacks an identity.” In an article about Reverend Gretta Vosper, Todd criticized the United Church’s decision to allow the self-identifying atheist to lead a Toronto congregation. He called this a “sign of an institution without a definition, which lacks confidence.” He also detailed his disapproval of the Observer’s introspective history. Todd wrote:

The cover story of the November issue of the Observer maintains anti-[B]lack racism is pervasive in the church. June’s #MeToo cover gave prominence to nine cases of alleged sexual harassment within the church. The May cover story chastised United Church members for supposedly marginalizing pregnant clergy. The magazine has prominently featured a disabled clergyman claiming members treat him as invisible. And the Observer’s readers are frequently taken to task for failing to properly reconcile with Indigenous people. The scolding goes on. In regards to spiritual topics, readers of the magazine, which is devoted to ‘faith, justice and ethical living,’ usually have to go to the back pages to find more than fleeting references to Jesus or Christian theology.

[su_dropcap style=”simple” size=”10″]I[/su_dropcap]n 2016, the Observer partnered with The Walrus Foundation for a Toronto speaking event called “The Walrus Talks Spirituality.” Bell says that over 500 people attended, and that nearly 1,000 others, many of whom had gathered at United Churches around the country, watched online. Since the rebrand, United Church members remain the core of the magazine’s subscribers, at 90 percent. Subscriptions make up about 36 percent of the magazine’s total revenue. The magazine also continues to fundraise as a registered charity, through its Friends of Broadview campaign, which asks people who visit its website to “help us share stories of spirituality, justice and ethical living from a progressive Christian lens.”

[su_quote cite=”Reverend Martha ter Kuile”]One of the issues is whether that link in people’s minds can ever actually be broken…whether its core audience will ever think of it as anything other than the one place where you can find out about the church [/su_quote]

Pam Harrison, who sits on the Broadview board of directors, says she feels she is “the voice and the eyes and the ears in Atlantic Canada.” She voluntarily shows the magazine to churchgoers as part of Broadview’s subscriber-maintenance efforts. While she is preaching, quite literally, to the converted, she tries to get people excited about the magazine. Harrison stands at the front of the congregation, holding up the magazine and telling those present about its newly strengthened spine. She then passes the magazine out to the congregation so they can all touch it together. She asks the congregation if the font size is easy for them to read. In an attempt to expand its readership, Broadview has also started to exchange in-magazine subscription postcards with The Walrus, Maclean’s, Zoomer, Maisonneuve, Herizons and Reader’s Digest, along with other Christian publications such as an evangelical Christian publication, Faith Today and the United Church head office publications, Mandate and Gathering.

[su_dropcap style=”simple” size=”10″]W[/su_dropcap]alking toward Reverend Martha ter Kuile’s spacious office in the Bloor Street United Church, black and white photographs of previous ministers line the stairwells. The wooden bannisters creak and echo with tradition and history. Inside, the sun blazes through multicoloured window inserts while ter Kuile sits on a blue-green couch. The weather is warm, but she puts on a sweater—the stone walls keep the church cool.

“I’ve always thought of it as a church magazine,” says ter Kuile of Broadview. She says the magazine still maintains a religious identity, but is concerned about the publication’s intention to evolve its audience. “One of the issues is whether that link in people’s minds can ever actually be broken…whether its core audience will ever think of it as anything other than the one place where you can find out about the church.”

Ter Kuile says it’s too early to predict how the rebranded Broadview will fit within the mission to preserve the longevity of the United Church. She cautions that “it will soon leave a gap in the United Church that really can’t be filled.”

“It was absolutely needed,” she continues, referring to the Observer. “…It defined the flavour of the United Church in a way that official meetings of the Presbytery and policies from the national office could never do.”

Despite ter Kuile’s concerns about the rebrand, she understands Broadview’s need to reach additional audiences. “I don’t think anybody was against the notion that they should try to be relevant,” she says. “I mean, that’s part of the whole church…We carry this heavy burden all the time—how are we going to be relevant?”

For the Bloor Street United Church, staying relevant means renovation and redevelopment. Much like Broadview’s rebrand, ter Kuile says the Bloor Street United Church, too, will undergo a process of modernization. The building will still operate as a church, but a highrise is set to be constructed behind it. Current renderings appear to maintain some of the exterior walls while the interior and adjoining highrise symbolize bold expressions of change. The space will continue to be shared with the City Shul for its Saturday prayers, and ter Kuile says it will be “refurbished in such a way that everything is accessible.” Two floors of the incoming condominium will belong to the United Church of Canada, which is currently located in Etobicoke, west of Toronto. The interior walls will come down, and a glass atrium will be installed to connect the United Church of Canada to the United Church congregation. She says this design shows that, “this is a historic institution that still has something to do, something to say and still has a calling in the world.”

[su_dropcap style=”simple” size=”10″]O[/su_dropcap]n a Wednesday morning in November 2019, Broadview’s editorial team is crowded in the boardroom. Large prints of old Observer covers hang on the wall as the team goes through their March issue lineup. They discuss an important section in the back of the magazine, which they have deliberately kept intact. Called The United Church in Focus, the section is devoted to “News About Canada’s Largest Protestant Denomination.” In this issue, the section will include a story about a Toronto church giving back to its community through youth programming, alongside news of a minister’s retirement and a story about a shared United-Anglican ministry. The team then switches focus to another section, known as Question Box, a space for ministers to pose questions. The March issue’s question reads, “Our church is starting to talk about how we can offer more content online and through social media. How can we get started? Is there anyone who can help us?” Christopher White, a United Church minister based in Toronto, offers suggestions and describes online engagement as a matter “of increasing importance to every community of faith.” Most of the magazine’s stories are punctuated with a small “B” endmark. But this section, which caters to United Church readers still ends with “UC,” a gesture to the loyal audience who’ve been with the magazine all along.

In 2017 and 2018, the magazine experienced an eight percent loss in subscribers. But since the April 2019 rebrand, the amount of subscribers lost has gradually lessened, to under two percent. Despite some expected attrition, the margins of subscriber-loss are shrinking. Bell attributes this to marketing and circulation efforts to keep their current subscribers while appealing to new readers and communicating their rebrand to stakeholders and United Church members.

In the March issue, Bell’s editor’s note refers to two features tackling female genital mutilation or cutting, one by Khozema, and the other by Roberta Staley. “Both stories are not easy reads,” writes Bell. “But I hope you won’t shrug, sigh, get angry, or turn away. They took so much courage to write, and they offer so much hope for the future.” Her words mirror the fortitude of Broadview itself.

As the magazine’s quest toward evolution continues, Bell’s faith remains unshaken. Broadview’s first Post-Launch Reader Study showed that 85 percent of respondents were satisfied with the magazine. “We are getting closer to becoming sustainable,” she says in an email. “There’s still so much work to be done. But it’s headed in the right direction.”

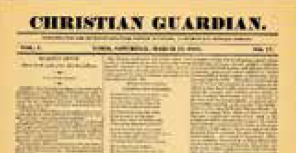

The Genesis

1829

1829

First Published

Original Name: The Christian Guardian

Original Format: a weekly newspaper documenting church life, politics, and education

Original Audience: Methodist Episcopal Church membership

Founder: Egerton Ryerson

1925

1925

First Rebrand: The New Outlook, following the formation of the United Church.

1939

1939

Second Rebrand: The United Church Observer, which amalgamated The New Outlook, The United Church Record and The Missionary Review of the World, and The Christian Advance. The United Church Observer was “the official organ of The United Church of Canada,” according to its first issue (March 1, 1939).

To be Noted: Despite being this organ, the first issue outlined that its editor remained free to discuss all topics within the church. The magazine was not to speak for the church, rather “as the occasion demands, to deal from the Christian point of view with issues of national and international concern, and with any interest affecting the well-being of human personality.”

1986

Independently Incorporated: This editorial independence has remained throughout its years of publication, even before it was officially incorporated as an independent entity in 1986.

2019

Third Rebrand: Broadview

Inspiration: The publication borrows the name from its nearby subway station, but the team chose the name as the word also represents “expansiveness” and “open mindedness” Bell says in an email.

—Ashley Fraser