Tourism is one of the largest contributors to greenhouse gas emissions. Here’s how travel-journalists are adapting to the continuing climate crisis.

In August 2021, Jami Savage was in one of the last cars driving along the Coquihalla Highway. She was making a three-hour drive from Vernon to her home in Hope, British Columbia. Thick, black smoke surrounded the area, making it nearly impossible to see 20 feet in front of her. Savage kept driving—her friend in the passenger seat beside her—even as wildfires raged around them. Savage continued through the smoke, later finding out the highway had been closed to travellers behind her.

Savage, a Langley, B.C.–based journalist, now has to consider the climate crisis when planning her travel stories. Wildfire is only one example of the natural disasters she has faced. Last September, she was on a working RV trip with her daughter on the East Coast. They flew out hours before Hurricane Fiona touched down. “I just feel like Mother Nature keeps hitting me with natural disasters to be, like, ‘You have a job, you have a voice, and you need to be part of the change,’” she says. Nine years ago, Savage created the website Adventure Awaits where she writes about sustainable tourism and outdoor adventures, to be part of that change.

Tourist Hotspots Catching Fire

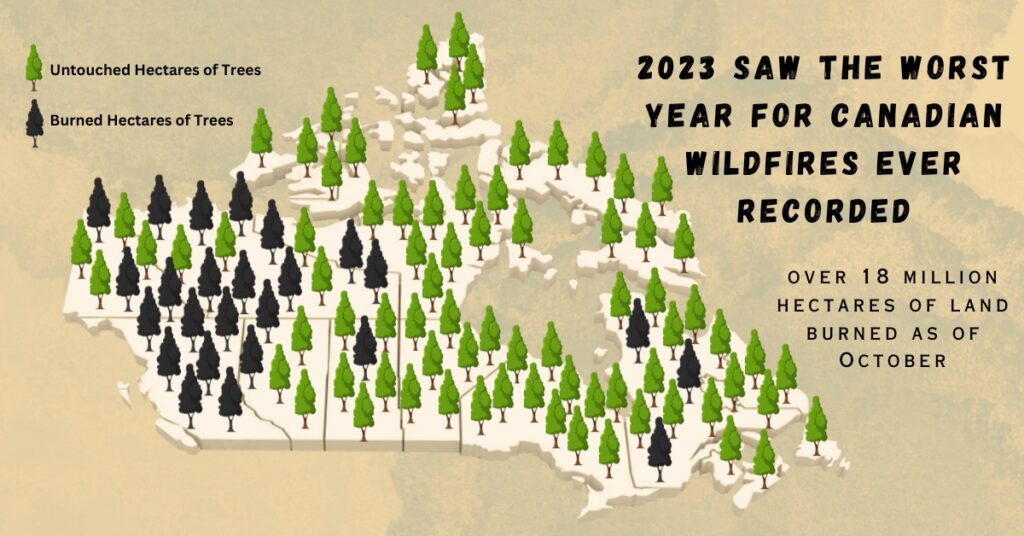

Already, 2023 is the worst year for land burned by wildfires in Canada, with over 18 million hectares of land burned as of October. This is over two and a half times the previous record, set in 1995. Research shows that climate change is linked to extreme weather conditions such as heat and drought, which can make wildfires more likely to occur. Tourist hotspots are also plagued with severe weather, with parts of Europe, North America, and Asia reaching record temperatures this summer. Maui, which Tripadvisor ranked as one of the most popular tourist destinations in the U.S. in 2022, faced a devastating wildfire in August that claimed the lives of at least 97 people.

Not only is tourism being affected by climate change, it is contributing to it. An estimated 8 to 11 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions come from tourism; a figure that scientists think could grow by 25 percent come 2030. Some of the biggest culprits are planes, cars, and other forms of transportation.

The changing sentiments around the travel writing genre are not new. In his 2019 book Horizon, the late travel writer and essayist, Barry Lopez, reflected on his over 50 years of travel by taking a new approach to the genre: urging travellers to recognize the environmental damage of the places they visit. In one instance, he describes standing on an ecotourism ship in the High Arctic in 2012 with two other travellers. “There was not a single floe in the waters ahead. Not a scrap of ice,” he wrote. Lopez and the others stood completely silent, struck speechless by the melted sea before them.

Like Lopez, some travel journalists are transitioning to writing about ecotourism, a form of tourism based on responsible travel to natural areas. According to David Fennell, a professor of geography and tourism studies at Brock University and editor-in-chief of the Journal of Ecotourism, this form of tourism has four components: it is nature-based, educational, sustainable for both the biodiversity and local communities, and ethical. When Fennell asks his students whether travelling to a national park automatically counts as ecotourism, he says most of them mistakenly say yes. “Ecotourism is an attitude and an ethic about how to approach the natural world,” says Fennell. “If you don’t have the attitude and ethic, you’re not an ecotourist.”

When she started her website, Savage always had sustainability and outdoor travel as a main focus. “The best way to explore a destination is on the ground, connecting with nature and culture and the people that live there,” she says. However, about a year ago, she transitioned to exclusively talking about ecotourism. “I want to protect the places that I love. How to do that is to become a more educated travel writer, tell better stories, help educate, and be a part of that change that I want to see in the world.”

Ethics of Travel Journalism

Josephine Matyas, another travel journalist based in Kingston, Ontario, is adapting how she writes. Matyas began writing full time 23 years ago, focusing on ecotourism and sustainability. When the pandemic began in 2020, Matyas shifted to writing primarily about RV travel, which she says uses fewer resources than air travel. In addition, she says she flies less frequently and spends an extended amount of time at a destination. To Matyas, it is important to focus on the climate change impact of how we choose to travel. “We’re seeing the impacts of climate change now, in heat waves and wildfires and the impacts of carbon. We need to treat destinations in a respectable way, to really represent what’s happening in places.”

Ecotourism also brings up important conversations surrounding the ethics of travel writing, including how tourists treat local people and areas. Travel narratives have existed for thousands of years, and critics often point out their exploitative and colonialist nature. The genre has historically set so-called civilized countries apart from non-Western tourist hotspots while appropriating land and resources.

The Antiguan-American writer Jamaica Kincaid echoes these sentiments in her 1988 work, A Small Place, where she writes that tourists who visit Antigua become a “piece of rubbish pausing here and there to gaze at this and taste that. It will never occur to them that the people who inhabit the place in which they have paused cannot stand them.”

This is especially critical when considering how Canadian travel journalists write about Indigenous communities. Diane Selkirk, a Vancouver-based travel journalist, advocates for sustainable and local travel, including Indigenous tourism. She recently wrote a feature for the BBC Travel website detailing how the National Museum of Scotland returned the Ni’isjoohl memorial pts’aan (pole) to the Nisga’a Nation in British Columbia after an extensive repatriation effort by members of the community. The pole was initially stolen by a Canadian anthropologist and presented to the National Museum of Scotland in 1929, with the community receiving no compensation. Selkirk says that when she writes about Indigenous communities, she asks the community for permission before writing the story and often allows sources to see their quotes in context and change them if needed. “I do a lot of research as well. I ask a lot of questions like, ‘How do you want a story told, what do you want people to take away from this destination? What do you want me to tell people about it? What is important to you?’ So I’m not using it. I’m amplifying their voices versus giving my opinions,” she says.

Changing Directions

Selkirk is also part of the board of directors of the Travel Media Association of Canada (TMAC), an organization of almost 400 accredited Canadian travel media professionals. According to Selkirk, TMAC provides travel media with a standard of professionalism and a code of ethics. Savage is a member of TMAC, as well as the Transformational Travel Council Herald Program, a network of travel media professionals who receive opportunities and meet together to encourage local travel journalism. The council also aims to promote reflection, understanding, and mindful action for travellers. “It’s a really powerful organization to be a part of in terms of actually talking about what the future of travel possibly looks like,” Savage says, “tackling some of the hard, hard questions.”

They also offer certifications that can help journalists gain a better understanding of whether businesses meet ethical standards. For instance, in 2020, Savage took an intensive course with the council to become a certified Transformational Travel Council Designer, which allows her to plan transformational trips, a type of travel rooted in becoming more conscious about travelling and its impacts through personal reflection, understanding, and mindful action. While she hopes to host trips in the future, she also says it helps her understand the principles behind ethical and responsible travel.

According to Savage, it’s up to journalists to act as one of the connections between travellers and businesses, helping to ensure the survival of humanity by telling stories focused on sustainability and ecotourism. “Our job, our opportunity, our responsibility, is to be telling those stories—to help educate travellers on how to be responsible travellers going forward. If we can shift that culture collectively, that will put the pressure on the big businesses to be the change that we want to see.”

About the author

Julia Tramontin is a fourth-year journalism undergraduate at Toronto Metropolitan University. She is passionate about women’s issues and mental health, firmly believing that storytelling can be transformative. Her writing has been featured in publications like Her Campus. When she’s not editing, she can be found reading or hanging out with her dogs.