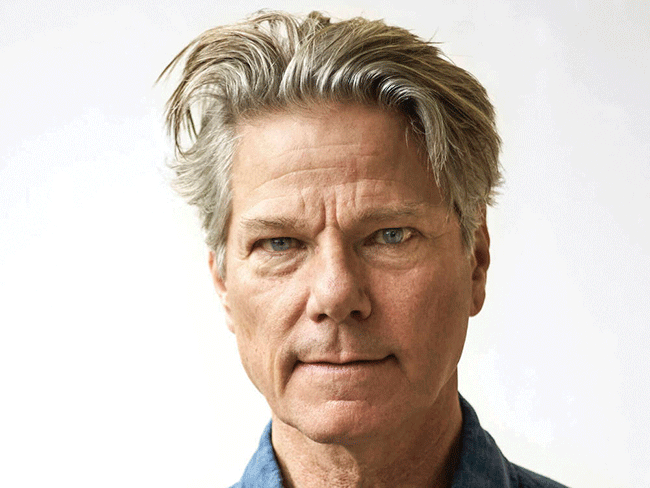

The Vancouver author of Fire Weather talks to the Review about Canada’s carbon awakening

In May 2016, the city of Fort McMurray in northern Alberta, population 80,000, went up in flames. It was Canada’s most devastating and expensive natural disaster to date. The wildfire swept through the community at a furious pace, forcing one of the largest evacuations in Canadian history. Journalist and author John Vaillant investigated the driving force behind the Fort Mac fire in his award-winning book, Fire Weather: The Making of the Beast, published in 2023. Vaillant’s investigation pieced together the petroleum industry’s large hand that looms over everyone’s daily lives—a hand that has been instrumental in making the world burn faster, hotter, and longer. Vaillant talks to the Review about his wake-up call to a world on fire, and how we need to prepare for what’s to come.

What was it about the Fort McMurray wildfire in Alberta that made you want to write a book about it?

Its size, ferocity, and durability. It burned in the city for days. It didn’t just blow through. A lot of big urban fires are over in a short period of time. This one stayed within the city limits for many days. Active firefighting was going on, in, and around Fort McMurray, for weeks afterward. The rain never came, the temperature never went down, things never dried out. Or rather, never cooled down or dampened. I saw this back in 2016, before a lot of the really bad fires we’re now familiar with. Australia burned in 2019–2020. Canada had its own “Black Summer” just last summer. The Pacific Northwest burned terribly. Fort Mac is before all that. Around 2016, Southern California burned, Australia burned, but not a lot of other places burned in ways that commanded headlines.

What I saw back in 2016 was that Fort McMurray is a very wealthy, well fortified city. It’s got a lot of people with technical skills. It’s got a lot of resources. It’s surrounded by two major rivers, pipeline corridors, transmission corridors, and actual fire breaks from previous fires. So if any city should have been able to hold off a big fire, it would have been Fort McMurray. It also has some of the best firefighting apparatus on the continent because of the petroleum industry. That’s a fire-prone environment in which you need highly skilled firefighters with state-of-the-art equipment way beyond what you would normally have in a municipal setting.

They had all of that and they couldn’t stop the fire. So I looked at the temperature—33 degrees Celsius. That’s normal for California; that isn’t normal for northern Alberta. I looked at the relative humidity, 11 or 12 percent. That is extreme for Canada, but normal for Death Valley. So now we’ve got conditions in the boreal forest that resemble desert conditions in Southern California. But with this huge fuel base in the form of the boreal forest, which is already fire-prone, and through the combination of low humidity and record temperatures, you’ve effectively sprayed gasoline all over it. That’s how it’s going to burn and that’s how it burned. It went off like a bomb.

Firefighters can’t fight that—they literally can’t fight it. So now we have this supercharged system. Fort McMurray became, besides the site of the largest, most rapid evacuation due to fire in modern times, a laboratory where we can study and learn about modern urban fire. That’s what I saw in 2016.

I certainly wasn’t the only person who saw that. Several other books were written much more quickly than mine. But I cast my net wider and went a little deeper into some areas and tried to create a synthesis that showed how the boreal and colonial appetites matched with the petroleum industry, changing climate and the culture of Western commercialism—and really, frankly, Judeo-Christian entitlement. The Bible gave us dominion over the earth and I know there are other religions and other faiths that have some similar overlaps, but in terms of the driving energy that moved across North America, that came out of the Bible out of Europe, out of capitalism and the colonial impulse. You really get to see all of that unfolding in Alberta, through the fur industry, through the patterns of settlement, through the displacement of Indigenous people, through the extraordinary exploitation of natural resources, and then the climatic blowback on that global exploitation of petroleum products. We’re in this moment now where we’ve completed the circle, and there’s nowhere left to go now. We actually have to back up. That is completely anathema to the capitalist impulse and to most of the leadership in Canada and the West today.

Your book is divided into three parts. What went into that decision when you were writing to synthesize and dedicate each part to a specific angle?

As a writer and a journalist you have a complex topic, and how do you organize it in a way that you can manage intellectually, logistically, narratively, and then work it into a form that a reader such as yourself can engage with in a way that’s not overwhelming, chaotic, diffuse? So, the three parts, I don’t know if it’s a cheat, but it is an effective way to grapple with cumbersome topics, and I recommend it. Also, I just think stories move in threes—there’s something about the number three in terms of sequences or sections that just work for human beings or for our consciousness.

There’s sort of a backstory of front-loading. I do that in The Tiger and also in The Golden Spruce [Vaillant’s second and first two books, respectively]. It takes time, and the fear is that it’s going to bleed off the reader’s energy. So you try to keep it [“Part One: Origin Stories”] quick and exciting because it is exciting, and that’s why I put it there. Then, you’re promising this meatier, more dynamic narrative, and that’s the heart of the book. That’s “Part Two: Fire Weather.” That’s the fire in Fort McMurray. But if it just ended with the fire, what have we learned? We’ve just been on a hair-raising adventure, but it’s too late for that. I’m not really interested in disaster stories—I’m interested in how disaster relates to our larger understanding of the world and a way to move forward in this more dangerous place that human beings have created. That’s what “Part Three: Reckoning” offers, a way of understanding and contextualizing. And, also, it’s just helpful, rather than to be in reaction to every catastrophe that’s happening. To understand there’s actually a framework that they occur within. And there are choices that we made, or that governments and industry made, with our help as consumers, to get us into this situation. But also, there’s not a pathway out, but a way to negotiate with and mitigate this reality that has been created. That’s where Reckoning leads into, and that story is not done.

“Fire is the only natural disaster that can be initiated by a gesture as casual as dropping a match.” — John Vaillant, Fire Weather: The Making of a Beast

Every book, eventually, you’ve got to pull the plug on it somewhere. And this story isn’t finished. The jury’s still out. A lot is going to happen. It’s already happening with insurance. Whole regions of the continent are now not being insured for fire. That was unthinkable 10 years ago. Things are really moving fast. Also, petroleum companies are getting sued all over the world in ways that they never imagined. When I was a kid, petroleum was a blue chip stock. It’s what made the world go round. You invested in it, you partook of it, you were grateful for it. Now we’re at this new stage where we still have to somehow recognize what petroleum has given us. How do you show your gratitude and, at the same time, say it’s now working against us? Anthropogenic CO2 and methane are already making parts of the planet unlivable. We have this colossal reckoning. Canada, next summer, is going to be a scary place.

This is a national problem. It’s a national security problem and national safety problem. It’s also a social justice problem. Look at who’s influenced the most, impacted the most, by intense heat, by fire evacuations. Those are often more vulnerable segments of the population. It’s a huge reckoning on a kind of national scale that touches every aspect of our lives. The upside of that is, it’s an invitation to renegotiate our relationship with nature, and with each other, in a much more wholesome, balanced, and sustainable way. Rather than: How can you buy the biggest truck you can afford? How can you buy the biggest house you could afford? How can you consume the most? We have been persuaded and hoodwinked into thinking that more consumption is a manifestation of personal freedom and, actually, it’s going to constrain us. A big house burns bigger. A big truck burns bigger, runs out of gas sooner. It’s the petroleum industry, the banking industry, and many governments, working at cross-purposes with what we as humans and citizens of the planet need most desperately right now.

In the book you write, “In the past 100 years, our planet has become a flickering universe of fires large and small. Imagine being able to see them all.” What do you see when you look at something as menial as a teapot, a car, or even a house? Do you see fire?

Now I really do; I didn’t used to. I was born in the ’60s. I’m a product of peak petroleum. And, in the ’60s, people believed “Better Living through Chemistry.” All kinds of medications and drugs were being invented. Everybody was getting cars. It was an incredibly prosperous, expensive time. Earth’s systems weren’t feeling the strain the way they are now. The population was a fraction of what it is now—under three billion when I was born. There were just not that many people around, relative to what and who we have today. So it was a very different time and we took it all for granted. You just assume that’s the way it is. Only by studying history, only by travelling, do you see that there are these other realities around the world and other times in history.

There’s a heat element to this. I have a gas furnace. When the thermostat hits a certain level, that thing is going to heat up and ignite gas and set off a fire in my basement. I’ve got a hot water heater, also powered by gas, right now. There’s a pilot light that is burning all the time while I sleep, while I’m awake, when I’m on vacation—it’s burning and there’s a fire in my house. I don’t feel endangered, but it’s interesting how comfortable we are with fire. Likewise, when you think of the gas tank in your car, where is it? Right behind your kid’s car seat. We have brilliant engineers working. We’ve made it relatively safe, but it’s still a weird idea. The other thing that we haven’t really got around is the incredible toxicity of gas at every single stage as soon as it’s released from the ground in its liquid form. It’s highly toxic in vapour form. It’s highly toxic and it remains toxic through every stage of its production and use until it goes including when it goes into the environment. It’s constantly toxic. We have an energy system and economic system that is dependent on poison. It’s in real time, contaminating our world, our life-support system, as we speak.

“Every single climate metric—ocean temperature, ice loss, air temperature—is redlining right now.”

You would never gas a person to death—that is a crime and an insane thing to do. Yet, that is what we’re doing to our atmosphere. For those of us who are engaged in the modern world and look forward to hopping on a jet to go see our families or driving the car to work, we’re participating in that and enabling it. Governments and large corporations would be happy if we never said a word about it. That is a terrifying thought, because they fully know what they’re doing. They fully understand the implications. That’s why the Zuckerbergs of the world are building $100-million bunkers to keep themselves safe. When you look at what the Zuckerbergs and the Musks and the Bezoses are doing, we are totally expendable to them. We make them rich, and they’re going to burn us. These people who shape our world are quite happy to take the money and run. That should enrage people. It’s extremely insulting.

What was your experience when you were there, speaking to people who have suffered? In the second chapter, there are riveting stories from families.

Incredible, heroic people who are not interested in connecting the dots around their industry or climate change—it was just a really bad fire that they had to get through. There is a famous saying by a famous American writer named Upton Sinclair from 100 years ago. It’s in a book that he wrote called I, Candidate for Governor. “It’s difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends on his not understanding.” That’s never truer than for people in the petroleum industry, whose fortunes are totally dependent on them keeping their heads down and doing their jobs. They’ve made sacrifices to move their way up. They’re far away from their extended family. Very cold, difficult environment, obviously a dangerous environment to make a living and create a life for their kids that they may be unable to elsewhere.

I didn’t push them on it—they’d been through enough already—but nobody brought it up. Nobody talked climate with me. And there’s abundant evidence. It’s all in the book—you can look at the Keeling Curve of CO2. You can look at the temperature increase. You can look at what an insane year 2023 was by every single climate metric—ocean temperature, ice loss, air temperature. Every single metric is redlining right now.

Were you aware of the synergy between greenhouse gas emissions and hydrocarbon extraction, or did this come up when you dove into the history of the industry?

The climate science around the intersect between CO2and rising temperatures and flammability has been in the news, in science, since the 1990s, certainly. I was an adult in the ’90s, but I was busy doing my own life, like most of us are, and wasn’t super-focused on climate. I did see the headlines talking about warming and I did have an awareness, as a young person, that things seemed to be colder in the old days. People talked about that in the 1960s and ’70s and didn’t connect it to petroleum. I certainly had an awareness of it going into this story. It just got a lot more granular.

The closest analogy, of course, is the tobacco industry. In the ’60s and ’70s, people really began to understand that the cigarette industry was covering up and obfuscating the clear science around the connection between cigarettes and pulmonary health, and they were able to because they were so powerful in such a huge part of the culture. Everybody smoked. When I was a kid, you could smoke in the waiting room in the hospital, you could smoke on the plane—things we can’t imagine now. It sounds crazy. You’re sitting there, waiting, the dad can’t be in the delivery room with his wife and the baby, but he’s sitting outside smoking away, breathing right into the baby’s face when it’s born. Just bizarre, but that’s how it was. That’s where we are now with gasoline and we’re really at that stage of your generation and your kids and my kids are going to look back and say, “What were you thinking?”

Reading this book, it was like, Oh, my god, it’s right in front of me. You know this stuff, but you don’t really think about it.

I’ve heard other adults say, “Oh well, the kids will figure it out.” I reject that. This is a real moral quandary for me because I’ve heard Baby Boomers say, “Oh well, I’m glad I’ll be dead because, you know, this is all going to hell and I’m glad I’m going to miss it.” Imagine how hurtful that is to say. I worry that’s a message young people like yourself are getting. I just want to say, as an adult—as a parent—it’s a shameful way to talk. We’re here with you. We have expertise and resources and our love for you young people.

“Every barrel is more poison, more pollution, compounding an already untenable amount of pollution.”

I’ve got two kids. I want them to enjoy themselves and learn how to be good human beings. Their job is not to solve the climate crisis. That’s our job. You’re going to have ideas about it and ways of understanding it that will be more evolved than ours—because I was raised by people from the 1930s, I’m a creature from another century. And I know that the 21st century people—two of them are my kids—see the world and experience the world very differently. They bring a level of inspiration and invention that I just don’t have because of where I’m from. So, you’re not alone. And I feel very committed to being part of keeping this world a safe and productive place so that you can enjoy it.

I appreciate that and your book does that exactly. You end on an optimistic note and you end on a specific word, viriditas. How do you believe people can move toward that green energy you talk about?

Viriditas. The greening energy. It’s beautiful, and we are products of the earth. Before we became burners, we were growers, we were nurturers, and we’ve always raised our children. We’ve always loved our children and that’s the most beautiful garden of all for a parent. We are gardeners and nurturers and caretakers, and this impulse to burn for money is perverse. It’s unsustainable. We just happen to be alive, you and me and a few billion other people, in this moment, when that impulse is peaking and grooving, how unsustainable it is. So we’re actually alive at this amazing period of awakening.

It’s not always fun to be woken up at six in the morning on a Saturday by someone doing construction next door. You feel angry at the person waking you up sometimes, but we are being awakened right now to the unsustainability of the current mode. The really positive thing is there are so many ways to be in this world. Many people are trying all kinds of different modes, many of which are more sustainable than the one that banks and petroleum companies would like us to follow. But it’s going to require some effort on the part of the individual to look for those alternatives, and to see how they might fit into it all. It’s just amazing what’s going on right now in terms of renewables.

“Revamping the global energy system is not going to happen in two years. It’s a generational project.”

Texas, run by really hardcore right-wing, anti-abortion, anti-climate science, anti-women, really fundamentalist, derives about three-quarters of its electricity from wind and solar. On the other hand, it’s like the oil capital of the United States. Some of the biggest gushers that were ever drilled were in Texas. It’s famous for oil money. George Bush came from an oil dynasty. His father came from an oil dynasty. A lot of what’s wrong and corrupt about the world also comes from the petroleum industry. It’s the families that run it. But, at the same time, Texans are smart, canny, hard-working people and they know a good deal when they see one. And renewable energy is a good deal.

North Dakota is another place. It’s a backwater, just south of Manitoba. Tiny population, windswept, very conservative politically, and they’re getting about 85 percent of their energy from wind and solar. So, it’s not a political thing. Look at what’s happening in China, and India is also making real progress. This is happening almost logarithmically right now. Revamping the global energy system is not going to happen in two years. It’s a generational project, but it’s happening extraordinarily quickly.

Right now, we have to honestly face the fact that there is also more petroleum being produced now than ever before. The Alberta tar sands broke the four-million-barrels-a-day mark, which they’ve been trying to do since Stephen Harper. That is a step backward. Nothing good is going to come of that. Every barrel is more poison—in liquid form, in residue form, and the energy that’s required to refine it—just more and more pollution, compounding an already untenable amount of pollution. That’s the world that we’ve always lived in, where there are these progressive, positive trends, and these really dangerous negative ones. There are some terrible wars going on right now, and there are governments doing things that were unimaginable when I was a kid. There are governments treating their citizens and their neighbours in ways that are totally shocking and I think—just the reality of existence—there are these beautiful sunny days when the bulbs come up, and there are these terrible storms and fires, and they always happen.

We’re just dealing with that, but for a young person, I would advise them to focus on the positive trends that give them energy and make them feel excited, and look like they’re part of the world that they want to live in, and go toward that energy.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

About the author

Prarthana is a second-year Master of Journalism student at TMU. She’s an assistant reporter at the Investigative Journalism Bureau and a producer for Beyond the U podcast series at Toronto Met Radio. She additionally has work published in Maclean’s, Broadview, and other publications. She is passionate about sharing socio-political stories about displaced and vulnerable communities on a global scale.