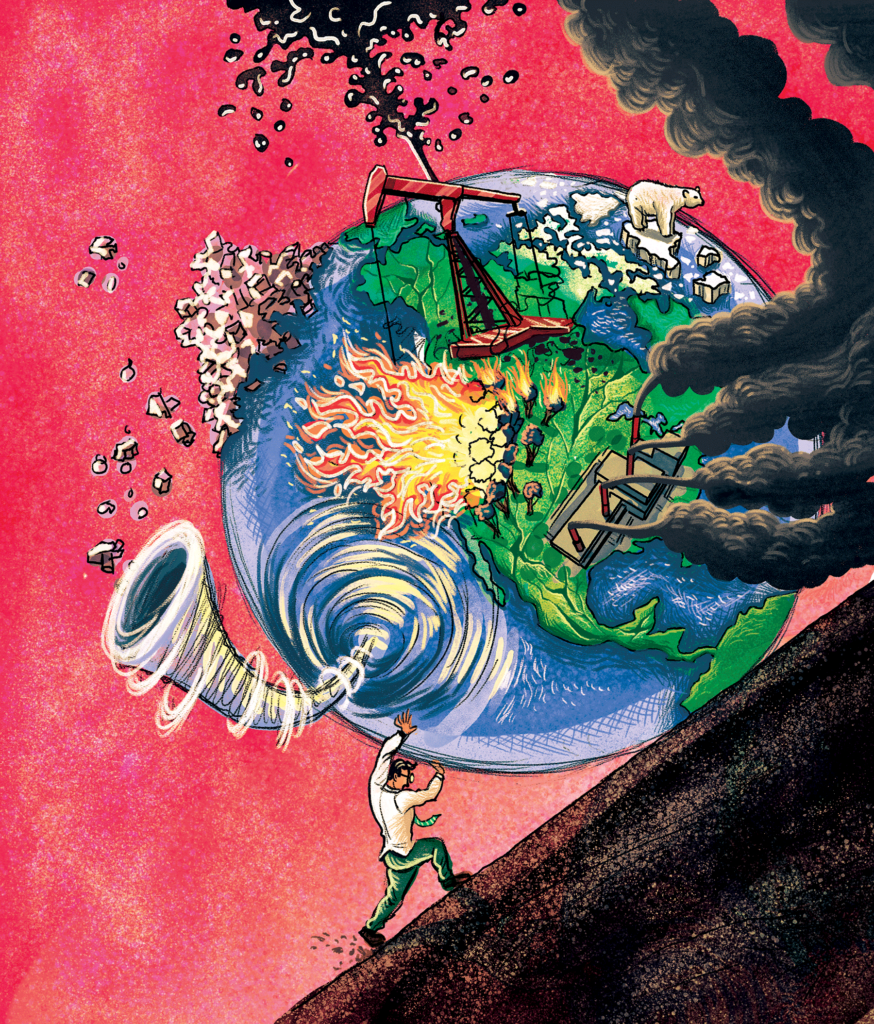

Fully informing people about the increasing dangers to a planet in peril is proving to be a Sisyphean task. How Journalists can rise to the challenge

In September 2019, climate change activism was trendy. Social media was full of signs with catchy slogans, such as: “I want a hot boyfriend, not a hot planet,” or “End Mother Nature’s hot girl summer.” In Toronto, more than 15,000 protestors took to Queen’s Park to march for change and action. It would have been impossible to silence citizens then, but since the pandemic, this empowering moment feels like a distant memory. “Climate change is not…a matter of the future—it’s a matter for now,” said Rahma Diaa, a freelance journalist based in Egypt, during an interview for the podcast Climate Tracker Weekly. According to the World Meteorological Organization, 2015 to 2020 have been among our warmest years in history—and global leaders are still not shaping up to meet the Paris Agreement standards of limiting global warming to 1.5ºC. “We are [at] an emergency point,” said Johan Rockström, director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research in Germany, at the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference in Glasgow. “We have reached the final decisive decade of our opportunity to land safely at 1.5 [ºC], and 1.5 is a real planetary boundary.”

One step forward and two steps back is how Climate Action Tracker describes Canada’s work toward implementing effective climate-action policies. For instance, according to CAT, while Canada may be working on its commitment to plant two billion trees in the next 10 years, “it continues to expand pipeline capacities for fossil fuels.” Even if the goals for Canada’s policies are fully implemented, it is not enough to reach 1.5ºC, and is more consistent with an astonishing 4ºC warming. As climate devastation looms, how can journalists better convey its magnitude? Some of the top climate journalists from around the world have offered their advice on how best to approach stories, reach citizens, and prompt action. Here’s what they had to say.

A Tsunami in the Sky: Search for a Creative Approach

“The best stories tend to come when you think creatively about why they’re important and how telling them in a certain way could make them more approachable for a wider audience,” writes Jack Board, climate change correspondent for CNA based in Bangkok, Thailand. Board was a finalist in the Columbia Journalism Review’s 2021 Covering Climate Now Journalism Awards, nominated for his multimedia piece “A Tsunami in the Sky: Climate Change Is Melting Bhutan’s Glaciers and the Danger Is Real.” Originality was a big part of what the judging panel looked for when reviewing the pieces. In his feature, Board explores how the glaciers in Bhutan’s northern mountains, surrounded largely by untouched land, could be permanently lost in glacial floods due to climate change, risking nearby communities, livelihood, and even the Punakha Dzong fortress, the second oldest and second largest fortress in Bhutan. Among wide shots of snow-capped mountains, people strolling along ancient bridges, and footage of Bhutanese festivals, readers are shown, through photo and video, exactly what will be lost in a nation at extreme risk.

When it comes to longer features, “You have to know how to tell a good story,” says Leonie Joubert, a science writer from South Africa. For some, this skill is inherent, and for others it takes practice. “I feel after 20 years of doing this…I’m now finally…getting to figure out how to do good storytelling,” she says. Joubert is an award-winning writer who has twice received an honorary mention in the Sunday Times Alan Paton Nonfiction Awards, in 2007 and 2010, and was named the 2009 SAB Environmental Journalist of the Year in the print/internet category. In “Rising Heat Puts the Kalahari’s Ecosystem on the Edge of Survival,” a recent feature for National Geographic, Joubert gives an in-depth look at how the complex ecosystem in the Kalahari Desert in southern Africa is threatened by rising temperatures and irregular weather patterns. “It has the skin of a balding man and whiskers like the eyelashes of a drag artist,” writes Joubert to describe the aardvark, one of many inhabitants of the desert. This use of creative language can captivate readers and make the ecosystem of the Kalahari seem understandable.

Climate Change or Climate Emergency? Why It’s Time to Be Aggressive

“I think reporters have a responsibility to tell the whole story,” says Kyle Pope, editor and publisher of the Columbia Journalism Review. “Sometimes that means being aggressive….Those are stories, and they can be read as political, but to me, it’s just great journalism.” Pope says “climate emergency” is one of the preferred terms at CJR, which, he adds, some find to be too focused on activism. “It just seems accurate to us,” he says. “It does seem like an emergency—and why not call it that?” Pope says it’s not journalists’ job to sugarcoat, but it is their responsibility to tell the truth the best that they can. For an issue as desperate as climate change, it is not the time to be particularly gentle with our writing.

Joubert is not one to shy away from activism when it comes to reporting on climate change either. She calls herself a science writer rather than a journalist because of the activist slant of her work—one that can sometimes break the strict rules of objectivity often found in journalism. Emily Atkin, climate reporter and founder of the climate-related newsletter, Heated, feels similarly. “Our allegiance as reporters is to the facts, and to the facts only,” she tells Brent Bambury on CBC’s Day 6 radio show. “I think we’ve become overly obsessed with making sure that our audience doesn’t feel offended if we report something that conflicts with their beliefs. We can’t let our readers’ perceptions of the facts make us shy away from telling them,” says Atkin.

Africa’s Damaged Ecosystems: Solutions Matter

“The most effective way to get people to respond to a crisis like this is to give them the hard facts about how bad it is, but then to tell them what the solutions are,” says Joubert. She clarifies, however, that it’s not possible to follow this approach with every story. In a piece Joubert wrote for The Energy Transition Blog in 2020 titled “Restoring Africa’s Damaged Ecosystems Is Central to a Just Transition,” she discusses how a Green New Deal-style approach to Africa’s ecosystems could mitigate the effects of runaway carbon pollution, but only with “political will, the necessary funding, and the right institutional arrangements.” According to Joubert, it’s more important to spur an audience into demanding political change than promoting individual acts. “I do think that the message here [in South Africa]—and you probably find it in your part of the world, as well—it’s still too much focused on individual behaviour change to mop up the mess.…[We] need to be driving the message that the big polluters need to be required to change,” she says. “That’s where our activism needs to be: not asking you and me to start recycling, but to demand that governments put regulations in place that throttles back on pollution…and that these large corporations be required to respond.”

Journalists are the ones educating people on these issues, so why leave the solutions up to the readers? As soon as people are given guidance in how to respond, Joubert says, they’re more likely to engage rather than bury their heads in the sand. Pope says climate change stories help to mobilize the public into action, and that people are more inclined to donate and support newsrooms after reading them. But, like Joubert, he thinks the “how screwed are we” genre is only half of the work. “I think those are important stories that people need to read, but I also think we need to offer—sort of along the lines of, ‘Okay, so now what do we do?’” he says.

Egypt and Polar Bears: Try to Be Relatable

It can be difficult for readers to care about news that doesn’t directly affect them; for journalists, making them care is part of the job. Climate change will continue to affect everyone on the planet, but telling the story in a more relatable way takes the message from “that sucks” to “that sucks for me, and what can I do about it?” For Rahma Diaa, finding that relatability is what she does. She was honoured as the top emerging journalist at the 2021 Covering Climate Now Journalism Awards for her intersectional stories that show how climate change is directly impacting her community. The Egyptian audience is not interested in reading climate change stories, she says, so newsrooms aren’t keen on publishing them. For Diaa, she gets readers to care about her stories by relating them to her audience’s lives directly. For example, her stories may focus on the health of those living near big polluters, how crops are being affected, or the lack of drinkable water. “I choose an angle like this to tell the people they suffer from this problem because of climate change….I tried to do this to make them feel the real dangers and the real effects,” she says.

“It’s actually well past time that we stopped thinking about it in a way that centres on polar bears and started thinking about it in a way that centres on humans”

Diaa understands these personal effects well. Her four-year-old daughter has had frequent allergy attacks from her continuous inhalation of dust caused by air pollution in Giza, affecting their lives in the Pyramids Gardens region. Her daughter now takes medicine every day to reduce these attacks. “Climate change can be a complex topic that viewers or readers quickly switch off from because they think they’ve heard it before,” says Board. “Harnessing dynamic human stories can help bridge the gap to understanding climate issues.” Atkin notes that the daily impact of climate change on our lives will only become clearer as the devastation gets worse. “It’s actually well past time that we stopped thinking about it in a way that centres on polar bears and started thinking about it in a way that centres on humans,” she says.

Lessons from COVID: Why All Journalists Should Be Climate Reporters

It’s easy to classify climate change as its own beat, but this crisis is an intricate web that touches on most aspects of our life and, as such, the news. With COVID-19, newsrooms learned quickly how the pandemic intersects with many important facets of our lives: economy, politics, and racial injustice are just a few. Climate change is similar, and just as all journalists have become pandemic reporters, all journalists should become climate reporters as well. “The COVID story has hit on the same themes as what we’re going to be seeing with the climate emergency,” said Pope during the Covering Climate Now Journalism Awards. “I think COVID has been very helpful in helping people frame how to think about the climate story.” Joubert mentions “the precious sports beat” and how even when climate change has been impacting the news around it, it still doesn’t get recognition for what it is. Take the annual Cape Town Cycle Tour, she explains, which sees about 35,000 cyclists per year. According to Joubert, this event has been cancelled or stopped halfway through several times in the last couple of decades due to extreme weather events, but the news has failed to report it for what it actually is: a repercussion of climate change.

Sandra Cuffe, a freelance journalist based in Guatemala who reports on human rights issues, says many of her stories end up relating to climate change, whether she’s writing about repression against communities, conflicts with mining companies, or activists’ struggle for land rights. According to Pope, this is what every journalist needs to learn how to do. One of the goals of Covering Climate Now has been to turn everyone into a climate reporter—though not necessarily full time. “We don’t want [newsrooms] to have a specialized climate reporter—in fact, I’m not even convinced that having a specialized climate reporter is that good of an idea. Why not just make everybody a climate reporter?” asks Pope. “Don’t think of this climate beat as some kind of weird, esoteric, standalone thing,” he says. “It’s something that’s affecting all of our lives, it’s affecting us right now. And if you’re going to be in the business of journalism, you gotta cover [it].”