Workers in revolt, unpaid wages, revolving-door management: inside five chaotic, difficult, tumultuous, teetering years at Now magazine

Beneath a small skylight, Jonathan Goldsbie is asleep on a couch. It is 4 a.m. in the height of Toronto’s Rob Ford era, and the Now magazine staff writer has passed out, as he often does, after writing through the night. The couch where he sleeps is uncomfortable, which is good: it will wake him in just a few hours, so he can do it all over again. His days are long, his beat is wild, and his job is hard. He wouldn’t trade it for the world.

Now was the ultimate guidebook to the city of Toronto. Founded in 1981 by Alice Klein and Michael Hollett (and a few others, according to Hollett), it was the key to everything going on that week. Editorially, it was a potent combo of cultural access and lefty political agitation. Brushing shoulders with rock stars, its writers cultivated a core audience of the coolest people and sold glimpses to everyone else. Yet by 2016, the golden days were ending. Backstage, tensions brewed.

Goldsbie recalls the members of Now’s staff union congregating in a church basement in July 2016. Their collective agreement was up for renewal, which in better times meant negotiations for pay increases. This time, the best their negotiators could ask for was a modest bump to wages and severance pay, at the cost of reduced benefits for certain staff.

By this point, Klein was now the sole editor, owner, and publisher of Now, with Hollett having left the picture earlier that year. Goldsbie, who was chair of the union’s bargaining unit, recalls that at times the paper felt like an extension of Klein.

She disputes this. “It wasn’t personal to me,” she says. “It was about the ability of Now magazine to continue to exist.” The paper had already been contracting for eight years and had ceased to be self-supporting. Klein began funding it herself. “We were very much in a live-or-die situation.”

With negotiations going nowhere and the company in dire straits, it appeared the July 21, 2016 issue could be its last. The union armed itself with the authority to strike. Goldsbie, fearing the worst, moved a dentist appointment to keep it covered by his benefits. Union leads handed out stickers and signs reading, “We Believe in NOW.” It never came to that: Klein and the union reached a deal, but only through intense negotiations.

At that point, Goldsbie referred to them as the worst experience of his adult life. He left Now three months after the move, burnt out and demoralized, jumping ship to a new alternative online publication, Canadaland. Its office had a 48-inch desk for him. Luxury.

Golden Years

Now was an alt-weekly: alternative to the mainstream dailies and publishing weekly. While one trailblazer, The Village Voice, began printing in the 1950s, the genre took off in the late seventies, when papers cropped up rapidly across cities in the U.S. and Canada. Their writers had the freedom to experiment and write subjectively.

In their heyday, they were also successful businesses. “I always define the alt-weekly as less of an editorial formula than an advertising formula,” says Jack Shafer, former editor of the weeklies Washington City Paper and SF Weekly.

Citywide, alt-weeklies were the cheapest of advertising buys. Omnipresent, often free, and carrying a reliable menu of weekend events, these were some of the reasons why Now and its ilk catered perfectly to the younger demographic that advertisers were desperate to reach—although they were popular with older readers, too. They also ran ads that you wouldn’t see in a daily: escort services, phone dating, and cheap classifieds filled the back pages.

For a while, the profit line went straight up. In his book Smoking Typewriters, historian John McMillian notes that by the late eighties, some alt-weeklies’ profits were in the hundreds of thousands. By the nineties, readership skyrocketed even as dailies’ readers plummeted. But all good things end. Craigslist came for the classifieds. Dating went online. Google wooed the advertisers. All alt-weeklies suffered, and many died. The few that survive, Shafer notes, are those that can run marijuana ads. Now had lasted a long time, but it was not immune.

Now was a potent combo of cultural access and lefty political agitation–the ultimate guidebook to the city

Over its 41 years in print, Now had carved out a valued niche in the Toronto arts and theatre scene. Its reporters knew their beats inside out and could deliver deep dives on obscure local artists, reviews of amateur theatre performances, and profiles of artists who weren’t famous yet, but would be. Kids coming in from the suburbs would take a copy home, a souvenir from the big city.

A paper like that attracts, and nurtures, a particular kind of writer. Norm Wilner is a jovial, well-spoken man with an easy smile. A devotee of physical media, he has a home studio whose walls are lined with bookcases. One holds a large chunk of the Criterion Collection, a series of classic and contemporary films on home video.

But as Wilner would hear from management, audience habits were changing. He says SEO optimization began to influence editorial decisions. Unless a story had the word Netflix in it, it wouldn’t perform well online. In the spring of 2016, Klein blasted Wilner in an editorial meeting. “Why am I reading this,” she said, gesturing at his story on Canadian filmmaker John-Marc Vallée. “Why do I care?”

“He’s one of Canada’s finest filmmakers,” Wilner protested. “He made a movie with movie stars in it. It’s opening, and we talked to him about it, because that’s the job. That’s what you hired me to do.”

“Change is often received with resistance and dissatisfaction by some,” she wrote in an email. “Now was no exception.” Finding that their trademark artist cover stories were “a bust” online, management pushed for cover stories with new angles, wider readership, and a shelf life of longer than a week. This meant taking the focus beyond arts to weekly features on the city’s best restaurants and little-known landmarks, even an issue devoted to body positivity.

Beyond the cover, it was a lot of Netflix. Wilner would watch about 20 hours’ worth of shows per week, then write, and with whatever energy he had left, review the new films opening in the city that week. His average day grew to 16 hours of work, watching shows and writing clickbait.

Out of Cash

Richard Trapunski was hopeful when he entered the boardroom in the winter of 2019. The collective agreement Goldsbie had negotiated was now up for renewal, and union representatives had called their members in to give an update. In the two years since Trapunski had joined Now, the veteran music writer had watched the team shrink and saw fewer people shouldering ever more work. The freelance budget was carefully rationed. Anecdotally, he heard everyone worked more than 40 hours per week. Perhaps this round of negotiations was a chance to improve things.

It was not. Dejected, union representatives explained that staff were being offered a temporary 15 percent cut in pay and hours. Otherwise, they might lose the whole show. With no other choice, the union voted to take the deal. In theory, everyone would now work a bit less, and earn a bit less. In practice, everyone worked the same, and just took the hit. Trapunski’s overtime turned into time owed to him, yet he couldn’t take it. Who else would write the music section?

And so, they worked. The union tracked down a government employment insurance program that would top up workers’ wages, but it counted freelance cash against the rebate. There was no way around it: most people were making less money.

The truth was, there wasn’t much cash to be had. Now had lost access to bank credit years ago, and Klein was reaching the end of her own resources. “I was a volunteer for the last few years,” she says. “I was in as far as I could go.” Now needed a saviour, and it got one. “As luck would have it, an enterprise with not enough knowledge of the media business to know what they didn’t know came forward,” said Klein. A new chapter was about to begin.

A Saviour?

Strangers crowded into the boardroom, talking with purpose. Klein and Hollett were among them, so it must have been important. The day was Thursday, November 28, 2019, and the editorial team—expecting to hold their weekly editorial meeting and entirely out of the loop—waited awkwardly as the clock struck 11:30 and the crowd failed to file out. Whatever it was, it beat making the paper.

The following Monday, another set of new faces arrived. In the back of the office there was a small, separate room for production staff, and that morning, the newcomers invited management and the higher-ranking editorial staff in, leaving the rest in suspense.

As they arrived, someone saw it on Twitter: Now had been sold to Media Central Corp. Then, an editorial letter from Klein herself appeared on the website. “It is the end of an era in the life of NOW Magazine and nowtoronto.com, and the beginning of a new stage in NOW’s evolution…” So, the staff thought, we’re owned by Media Central. Now what?

Media Central, formerly known as IntellaEquity, wanted to unite North America’s alt-weekly newspapers under one banner. For a cool $2 million, Now would be its first such acquisition. That past July it had amalgamated with Canncentral Inc., a cannabis-news outlet. In its press release, Media Central boasted of Now’s wide readership and cachet among “the creative class.” Through Now, it would reach the world. Shortly afterward, the doors of the production suite opened, and the staff were brought in to meet their new masters.

Chief among them was Brian Kalish, CEO of Media Central. One employee said that Kalish dressed more like a flashy marketing person than a media executive. His résumé boasted executive-level positions at the Toronto Argonauts and a water purification company. It did not indicate editorial experience. His company’s mission was empire. It already had Canncentral, a fledgling online magazine focusing on cannabis. Now, it would consolidate 100 “urban media publications” across North America, creating an “audience of influencers” that could be monetized with online advertising, and paired up with publications focusing on e-sports, sneaker culture, and cannabis. Vancouver’s Georgia Straight, purchased three months later, would be its second alt-weekly.

Addressing his staff, Kalish made his position clear: Media Central was a public company, which meant his responsibilities were toward his shareholders. After all, he didn’t own the company—they did. This was enough to cause a shiver among the staff. From the beginning, Now’s owners were known and present: Hollett, Klein, and a few others. Who were these private investors? Checking the listing for Media Central at the time, staff would have found its shares trading for a fraction of a penny on the Frankfurt Stock Exchange.

Their new owner’s strategy was not new. In the nineties, new chains like New Times Inc. began gobbling up alt-weeklies across the U.S. In 2006, New Times acquired New York alt-weekly The Village Voice, which had been losing millions to Craigslist and dating sites for years. Cost cuts followed: over the next two years, half the Voice staff took layoffs or resigned.

Wrapping up his speech, Kalish extended an invitation to staff to meet him individually in his office. It could have been a warm gesture, but one employee thought there could also have been a darker subtext: “Please, come by,” Kalish seemed to be saying, “and justify your job to me.”

Nevertheless, the sale gave the office hope. Perhaps a new owner and a cash infusion were what they needed. As for the perceived undertones in Kalish’s speech, well, the employees had a union. What could go wrong?

Meet the New Boss

Dan de Souza was sick and tired of brunch. Hired in January 2020 as Now’s art director, he had produced more than 40 different covers for the February 20, 2020, issue, all perfectly brunchy, and all failing to impress Kalish. Losing his composure in front of his colleagues in the newsroom, he pleaded with his new boss to just take one. Yet Kalish wouldn’t budge, threatening not to print the issue. De Souza says Kalish demanded, in a huff, “I just want it to be sunny! Just put a sun on the front! That would make it brunch.” Exasperated, de Souza found a nice yellow plate that looked like a sun, put “some stupid type” across the front, and called it brunch. Kalish conceded.

The argument left de Souza on edge. Paranoid about Kalish’s approval, he would obsess over covers, second-guessing himself. Before long, however, he and Kalish learned to work together—mostly because the pandemic meant they were all working remotely. Not everyone was so lucky. On the way back from the washroom in March of 2020, de Souza passed a young Canncentral employee who worked closely with Kalish and greeted him before sensing that something was wrong. Entering the newsroom, de Souza was met with a sea of shocked faces. Moments before, the young man had emerged from his office, and addressing the room, announced that Kalish had fired him, adding that it was nice working with them.

The firing offence was a message in the company’s Slack chat the day before. Sick and fearing COVID, the employee had advised his colleagues to watch their health if they had been in contact with him. Whether it was intended that way or not, de Souza said the message read as a joke. Some of his colleagues may have spoken well of him to Kalish, and later that day he was reinstated—only to be fired by Kalish a second time almost exactly a month later. (Kalish declined to be interviewed for this story and did not respond to a written list of questions.)

This was not the only cut. Despite promising her an “exciting new role as our Chief Editorial Strategist,” Klein says Kalish deemed her no longer of value to the company. By March, she had left the paper she had helped found, kept alive, and edited for over 40 years.

Risky Business and Playing Hardball

Joints on the deck, halter tops and shorts in summer: In the early days, Now’s office was not a buttoned-down place. Although employees were never told what they could or couldn’t wear, or whether they could smoke weed, it became more professional as the years went on, but the new owners turned the clock back a notch. De Souza saw some Media Central staff ripping drags on their vapes in the boardroom after hours, filling the room with clouds.

Behind the scenes, their company was running on borrowed time. In February 2020, it borrowed $1.1 million at a 10 percent interest rate from a collection of investors, which would be due in two years. The collateral? Now and the Straight.

Media Central was not the first to try this gambit. Creative Loafing, an Atlanta-based chain of alt-weeklies, went deeply in debt to purchase Washington City Paper and Chicago Reader in 2007, just in time for the 2008 financial crash. By September of that year, Creative Loafing was bankrupt, and its papers were sold off one by one.

In December 2021 pay cheques started to come late. At the end of March, the owner filed for bankruptcy

Media Central had two years to get its act together or suffer the same fate. There were costs to be cut. It had inherited the 15 percent reduction in pay and hours, and in March staff received a company-wide email returning their hours to 40 per week—and keeping the pay cut.

In a hallway, a handful of panicking staff held an emergency meeting, according to Trapunski. They knew union negotiations weren’t going well, but this was too much. They called a vote for the evening of March 5, 2020, to give their negotiators the power to call a strike if talks with management broke down. Held in the United Steelworkers hall in downtown Toronto, it passed with only two or three members in opposition. This time, the union was prepared to play hardball. Armed with its new powers, the union could call a strike, or management could lock them out. Members hammered out logistics, set aside cash, and drew up picketing schedules. They devised a plan for an online strike paper, complete with its own editorial team, and reserved a domain—nowmagazinenation.com.

It would be loud, public, and impossible to ignore: the staff of Toronto’s most iconic independent paper, picketing downtown, publishing an anti-magazine. Trapunski began jotting down potential story ideas for the strike paper and took his things home from the office. It seemed like a funny idea, staying home for a little while.

Only a global pandemic could get in the way of something like that. Which, of course, it did. Just before the union could pull the trigger, the city shut down. With the office in chaos, the streets empty, and the media entirely distracted, the strike plans went out the window. The opportunity would never come again.

Hard Cuts

Kalish’s voice emerged tinny from the speakers, phones, and ear pods of his astonished workers. He was on the defensive. Several days before, on June 9, 2020, he had released a letter to shareholders stating that, with the disruption of the pandemic, Now would be “eliminating a focus” on arts coverage. Writers worried about their beats. Editors worried they would have to start editing articles about things that didn’t interest them. Kalish seemed to view it as a terrible misunderstanding. According to one listener, he would say, defensively, “That’s not what I said!” Staff on the call would read his own words back to him and receive the same response.

Two days later, Kalish issued a public letter to Now’s readers, lamenting that “portions” of the memo had been “sadly taken out of context,” and assuring them that “arts and culture have been the cornerstone of NOW and the Straight from day one, and they will continue to remain important facets of our publications.”

This was true. Like other journalism outlets, Now adapted to COVID. With few concerts to cover, Trapunski switched to business reporting. Glenn Sumi, the theatre critic, started a series of pandemic walks. Despite their efforts, the damage to Now’s reputation was done. Observers shared the memo on social media, and a stubborn perception that it had, in fact, abandoned arts coverage set in among the public.

It didn’t help that it was getting harder to find the paper. The pandemic had tanked ad sales, with revenues down 80 percent and falling. In a desperate effort to cut costs, management laid off the circulation team, many of whom were musicians and artists who delivered the papers for extra cash. Circulation was reduced to just 10,000 copies per week, a far cry from its peak output of 60,000. Distribution was reduced to the TTC alone, leaving Now’s rusty green street boxes, a fixture of Toronto’s streetscape, hauntingly empty.

Every job cut meant another task for whomever remained. Cuts to marketing and sales meant the editorial team inherited those duties, which Media Central called a bold new “omnichannel approach to publishing.” Yet no one person on the editorial team was put in charge, says de Souza, and all were already overloaded with work.

New Directions

Michelle da Silva’s holographic body hovers above the paper, which lies face-up upon a hardwood floor. Only inches high, she’s rendered poorly through a smartphone screen, with her shoulder-length black hair flipping out as she turns her head. She’s talking. “Mansplaining leads our music section, as we cover Toronto writer Alison Lang,” says the projection. “She shares stories from her new zine, Music Men Ruined for Me. There’s a long-standing myth that parenthood and art are incompatible….” The hologram goes on, a poor imitation of augmented reality game Pokémon GO.

Now’s former digital editor exists in real life, too, and in human dimensions. Her alternate reality counterpart was one of its forays into newfangled tech gimmicks. Despite being an early adopter of the web, in Klein’s view, like other legacy publications, Now had struggled to keep pace. In uncertain times, this meant throwing things at the wall to see what would stick. The AR gimmick didn’t: attempted in 2017, it was live for only a short period.

Overseeing the implementation of many of these ventures was Kirk MacDonald. Hired by Klein as a consultant in 2017, he came with a packed résumé: CEO of The Denver Post and publisher of Rocky Mountain News, COO of alt-weekly chain Creative Loafing, and several executive-level sales positions. Despite decades of running a successful alt-weekly, Klein says she struggled to command respect in the business world. “I needed an alpha male to bring in opportunity to Now magazine,” she says, “so I hired Kirk.”

Not everyone was impressed. Meeting the team at an all-hands meeting, MacDonald took the opportunity to wax poetic about blockchain, which he promised would save the paper. Baffled, Wilner asked what exactly blockchain was. In response, MacDonald “just babbled,” says Wilner. “He’s got that great confidence of a man who has no idea what he’s saying, but he knows if he keeps talking, he’ll get there and bring people around.” In an email, MacDonald recalled talking about his excitement regarding blockchain and AI. “I had a desire to do everything I could to try to help Now be sustainable,” he says.

MacDonald had one early success: he was instrumental in selling Now to Media Central. Under Media Central, MacDonald became senior vice president of revenue and operations of the company, and led Now in new and, to some employees, strange directions. In the early days of the pandemic, he wrote the business plan for an online obituaries page, dubbed “Epitaphs.” Needing to populate it with something, Now took any obituaries it had on hand—all of which were of famous artists—and threw them up. When curious customers loaded the page, they were greeted with a selection of the famous dead—not exactly grandma’s peers. Now didn’t sell any obituaries; the Straight sold just one. “I thought it could become a new critically needed revenue stream,” wrote MacDonald. “I was wrong.”

Meanwhile, Media Central was also trying new things. In July 2020, the company launched an e-sports brand, ECentralSports.com, which never found an audience, then tried to acquire BudTree.com, a now-defunct online marketplace for cannabis products. In August, it was producing branded copy for an online wine merchant. September brought digital ads for an online sports betting company. In October, a waterproof footwear brand.

These initiatives required more time and energy from the already beleaguered Now staff. “‘We would have to hire people to have a skeleton crew,’ is what we would say toward the end,” says de Souza. “This is just bones, just literally a handful of bones left.”

November 2020 brought a development: Kalish and the other three board members left, and an interim CEO with a brand-new slate, took charge. The clock was ticking. With the company’s debt due in little more than a year and the pandemic still raging, there was little time to make things work.

Staffers, still under the pay cut, demanded to know when their salaries would return to normal. According to one employee, when pressed in a town hall meeting, the new management said wages would be restored after the company experienced two quarters of profitability, optimistically noting that their losses were improving. This was true: digital ad revenues were picking up, and Media Central’s operating losses had gone from $1.3 million in the third quarter of 2020 to just $375,000 over the same period in 2021. “That was the real major stroke,” says MacDonald. “A lot went into that.”

But the company was still in the red. In a grim twist, union rules prevented one new hire from earning more than existing staff in an equivalent role, spreading the pain. She was forced to take a four-day work week at $32,000 per year— just over the cost of renting a one-bedroom apartment in Toronto in 2023.

Founder Alice Klein kept Now on life support with her own cash: “We live for more than money”

Media Central had the costly task of running two papers and several other ventures, keeping up with interest repayments, at a time when MacDonald says the local economy remained stiff and capital was hard to come by. By the summer of 2021, money wasn’t getting out fast enough. De Souza received calls from equipment suppliers, asking him if he could do anything to expedite payment for lenses and backdrops rented for photo shoots. The printer asked for cash up front. De Souza says editors couldn’t get cheques to their freelance illustrators and writers, and he stopped commissioning illustrations.

And yet, the investments in new ideas continued. In June 2021, Media Central announced it was helping develop an online news aggregator, Creator News, and a Substack-like platform, Creator Stack. Each of these projects would be funded entirely by third parties, though Now was given a licensing agreement with Creator News to “allow use of its content.” That September, MacDonald spearheaded the release of four Now covers as NFTs. (“So I must know a little something about blockchain,” he says.) Their sales never took off.

A change in messaging was afoot. By August 2021, company reports jettisoned any mention of consolidating alt-weeklies. Media Central began describing itself as a “media and technology company” and declared Now and the Straight to be “storefronts” for their other media holdings. Now existed to make readers read something else.

Out of Time

In December 2021, pay cheques started coming late. In February, some pay cheques were missed entirely, according to de Souza. Media Central was out of money, and the loans were due. On March 9, it announced that it was in default and had started negotiating with its lenders. Now and the Straight now belonged to them. MacDonald, who had been made president by the new board back in late 2020, remained, though others jumped ship. People were barely getting paid. When payments did resume, staff asked if they could be paid in installments, which decreased in size over time. Back pay accrued.

On March 31, 2022, Media Central filed for bankruptcy. This should have been the end. Why work for a place that can’t pay you on time? A steady trickle of staff took voluntary layoffs to collect EI. Yet a core group stayed on, believing management when they said that if they kept the lights on, a new buyer would take interest.

Management suggested the paper was just one big issue away from profitability. Now’s annual summer guide was a huge, 54-page smorgasbord of advertising revenue. Yet a magazine of that size was barely in their grasp. “That was the Catch-22 of the end of Now,” said de Souza, who kept working. “By the time that issue went to publication, I’d been up for two days straight working on pages and formatting.” Remembering, he makes a noise somewhere between laughing and crying. “It was just a freaking nightmare.”

In July, when pay stopped coming altogether, de Souza’s patience ran out. He was planning a trip to Hamilton to visit his dad. Having given up his car—without being paid, he couldn’t afford repairs—he went to buy a train ticket, only to realize he couldn’t afford the $13.60 fare. Furious, he declared himself laid off.

With the masthead atrophying, fewer senior staff took the lead. Copy editor Katarina Ristic became an associate editor back in June. Theatre critic Glenn Sumi jumped to acting managing editor, and a graphic designer from the Straight filled de Souza’s place for the next issue. Radheyan Simonpillai, formerly the culture and social media editor, had become acting editor the previous December. Of Tamil descent, Simonpillai says the alt-weekly was open to BIPOC writers when mainstream media weren’t. “I have a very personal connection to Now,” he says. “It’s literally the first outlet that gave me a chance to be a paid writer.”

And besides, who would cover the arts? “We were taken advantage of…we were misled, we were manipulated. We all have reasons to be angry and fed up,” Simonpillai says. “But for the love of the arts, and for the love of the community, and for the love of our team, we held on as long as we could.”

Not everyone is so romantic. Wilner resigned early in 2022 to become a programmer at TIFF. “That’s how they get you to work for free,” he says. “That’s how they get you to work 60-, 70-, 80-hour weeks for less than you made when they hired you. You just keep getting punched. You just keep taking it because you believe in what you’re doing.”

And yet, it was that passion that allowed Now to survive as long as it did, according to Klein. Hollett is fond of saying that their mission was journalistic, not profit-driven: but the profits meant that they could afford good lawyers when they pissed off power. Klein kept it on life support with her own cash. “We live for more than money,” she says. “We live for a purpose.”

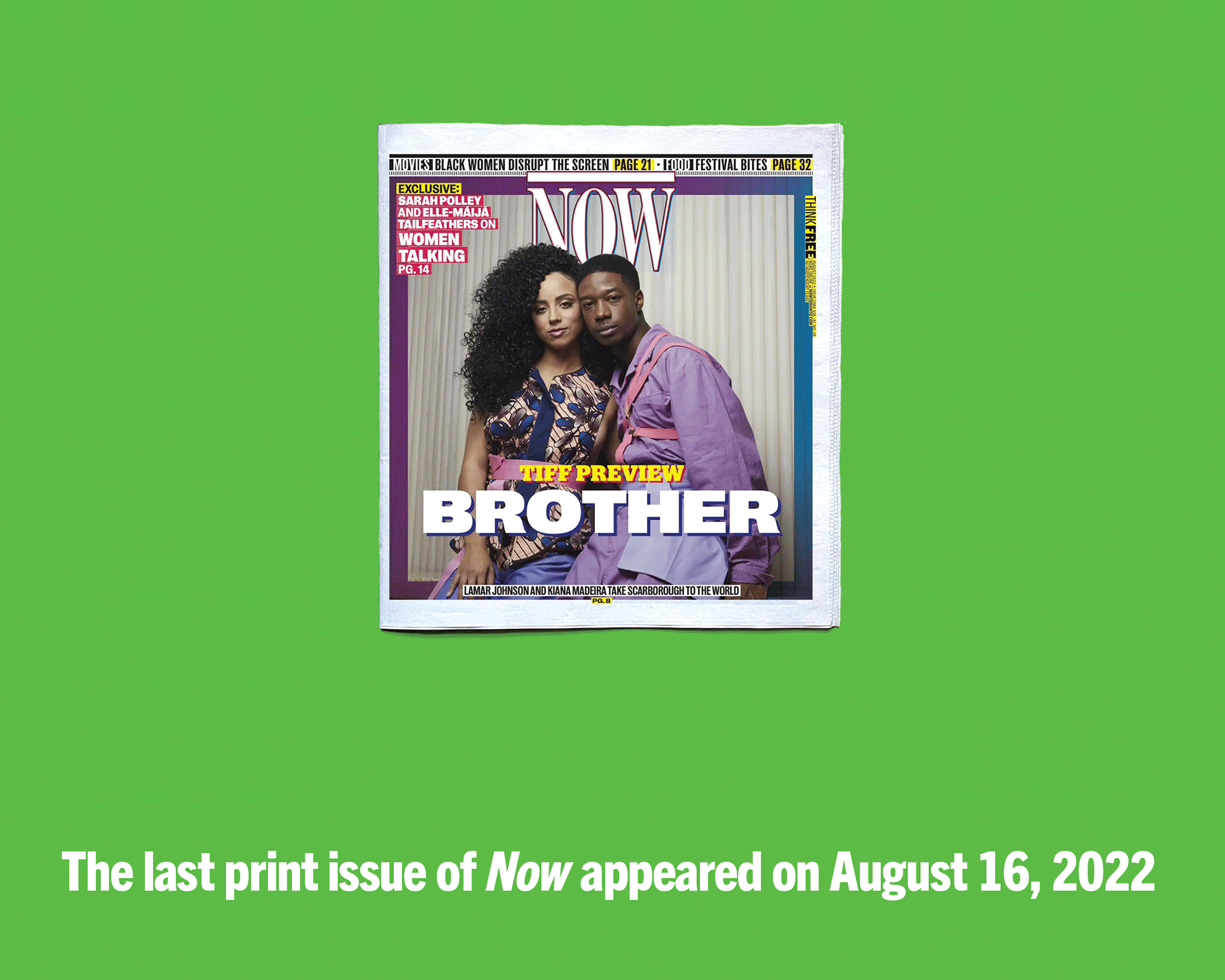

What was expected to be the last print issue came out in August 2022, the product of unpaid labour by Simonpillai and his team. If that was the end, Now died as it began: with a film festival issue, its cover celebrating Black filmmakers, on the beat until its last breath.

A New Hope

But it wasn’t the end. On December 22, 2022, Sumi announced on Twitter that he had finally lost access to his nowtoronto.com email account. Three weeks later, on January 9, 2023, a newswire release went out: Gonez Media, an online media company headed by reporter and YouTuber Brandon Gonez, had purchased Now’s digital assets. The website briefly went down, then reappeared, trading the iconic red-and-white colour scheme for a slick navy-blue palette.

As it turns out, MacDonald was still working. In an email, he says he remained on as “the last man standing” until December 2022, despite having not been paid since October 2021 and being “owed a significant amount of money.” In doing so, he says he “assisted the senior debt holder in selling Now to Gonez Media.”

In January, Gonez Media bought Now’s digital assets, but the former staffers wouldn’t get their back pay.

Reactions were mixed. On the one hand, the purchase placed a legacy Toronto publication under the direction of Gonez, a Black man, a welcome sight in the still overwhelmingly white world of Canadian media. His pick to lead the new editorial team, Kerrisa Wilson, would become the first Black woman to run a newsroom in Canada, according to the CBC. In a video posted to Instagram, several members of Gonez Media smiled and celebrated the launch of their new Now.

Yet not everyone was celebrating. In a quirk of corporate logic, Gonez Media managed to acquire Now’s digital assets without assuming its liabilities, meaning its debts to its employees remained with Media Central. Former staffers quickly took to social media to demand restitution, pointing out that stories they wrote without pay were still alive on the revamped Now website, and with ads on the margins—suggesting the new owners were profiting from their unpaid labour. Nor would they be hired back: in a statement published in the Globe, a representative confirmed Gonez Media would be “building a whole new editorial team from the ground up.”

And so, the story of Now, and the genre it represents, is still being written. As Toronto returns from its pandemic slumber, there remains no one destination to find all the week’s film screenings, amateur theatre performances, or weird shows by bands you’ve never heard of. Now’s absence left a hole, a question, an opportunity. The baton has been passed: once again, the future of Now remains to be seen.

About the author

Anthony Milton is a Master of Journalism student at Toronto Metropolitan University. Before entering journalism, he worked as a consultant in the electricity and climate space. He’s interested in longform writing and data journalism, about culture and politics. You can find his words in Toronto Life magazine, and his tweets at @C_AnthonyMilton.