Courtroom illustrators like Bill Robles have long been one of the only glimpses into courtroom proceedings, documenting what journalists can’t

Writers and visual artists share a common fear of the blank page but as someone who dabbles in both mediums, there’s nothing more hair-raising than laying down a line in permanent ink. But that’s exactly what iconic courtroom illustrator, Bill Robles, asked me to do when I sat down with his course, “Intro to Portrait Sketching: Draw in Real-Time” on Domestika, an online learning platform for creatives. In the courtroom, there’s no time to dither with a pencil sketch. Your art must be bold and brave.

A principle of common law, arising from the 1924 English legal precedent R v Sussex Justices, ex parte McCarthy states that “justice should not only be done, but should manifestly and undoubtedly be seen to be done.” Yet, while courts pivoted to allow Zoom cameras during COVID-19, cameras in Canadian courtrooms remain limited. And so, while the notion of the courtroom illustrator seems absurdly antiquated in an era where journalism moves so fast, their sketches are often the only eye the public has into legal proceedings. In short, courtroom sketching is journalism, not just art.

Robles’s course consists of 14 short video-based lessons designed to teach budding courtroom illustrators how to draw on-the-spot sketches of subjects in their environment. Sprinkled throughout are hands-on exercises that encourage students to practice what they’ve learned. Robles made the leap to courtroom sketching from his already-successful illustration career when the Charles Manson murders occurred in 1969. With 50 years of high-profile court drawing under his belt, this was the man I wanted to learn the discipline from.

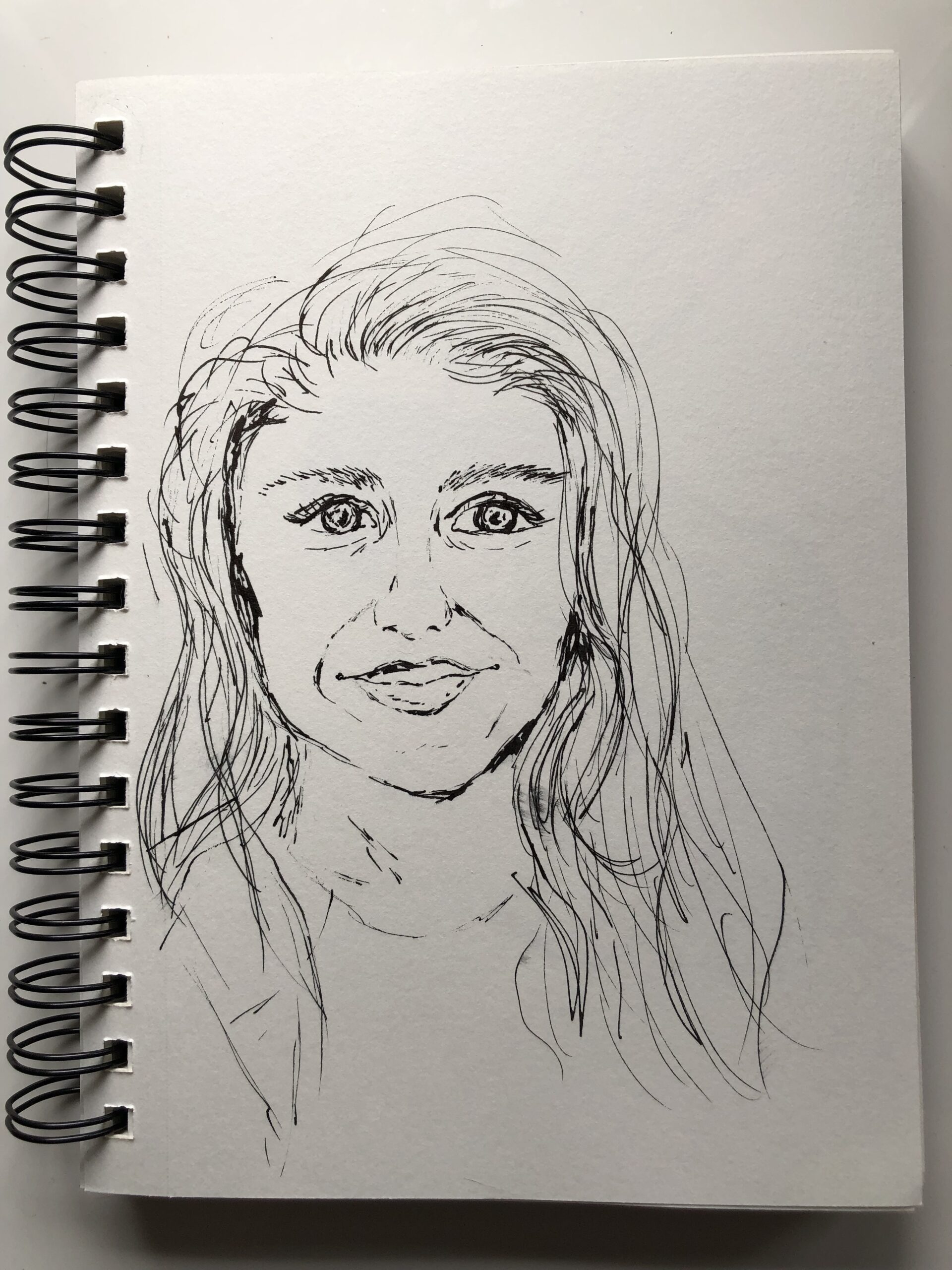

“It’s up to you to create your own technique and have fun with it,” Robles assured me as I embarked on the first set of lessons about drawing the human head. Now, I wouldn’t call drawing the noggin a beginner project—and not just because preparing minimal base sketches to guide my painting is the extent of my drawing expertise. Indeed, Robles validated my anxieties when he explained, “the hardest part in drawing the human head are the proportions”—in other words, exactly what you need to create a realistic sketch. And he wanted me to tackle this in pen?

Dressed in a collared shirt and jacket, Robles reminded me of an experienced journalist turned j-school professor that I’d interviewed in the fall: stern and authoritative, with a hint of warmth borne from dealing with newbies, a combination that instantly instills confidence. Robles demonstrated his approach to the head by sketching Mark Twain. Starting with Twain’s eyes and distinctive brows, Robles showed me how to use a light touch with the pen so that what seems permanent can be corrected. In the worst-case scenario, Robles has a backspace key: a razor blade which he uses to scrape ink from the page. But the trick to establishing proportions, according to Robles, is to look at the shapes of the face “almost as a jigsaw puzzle” with the goal of duplicating them, rather than drawing in every detail.

To my surprise, this worked. My first-ever drawing of a human head looked like a real human woman. Caveat: It did not look like the reference photo.

“Those court drawings never look like the people anyway,” my father observed later while I drew him for the course’s final project. He’s not wrong. Though there are no official rules governing Canadian court artists, some general advice can be gleaned from Canadian Press guidance on pictures.

“Good photos have similarities to good stories,” it counsels. They show something new or unusual, portray in-the-moment action, and either summarize a story “or provide an overall view of it.” Great images are “marked by attention to quality, content, composition, lighting and timing.” Of course, they appeal to our emotions. Importantly, digital enhancements must be minimal.

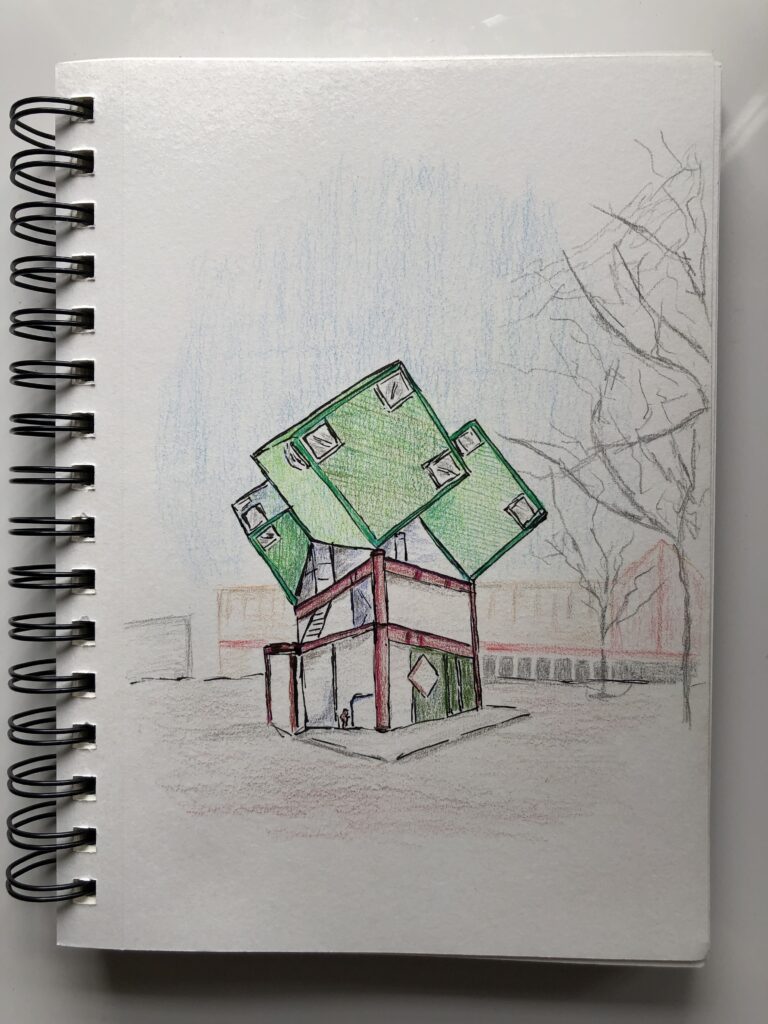

Buoyed by my success with the head sketch, I dove into the next section—drawing a full figure—in which Robles demonstrated his unique style achieved by smearing xylene-based Chartpak AD markers on vellum paper. I’d wanted to go full Gonzo for this project and use the same materials as Robles. Unfortunately, one whiff of an AD marker at the art supply store convinced me that I’d be using what I already had on hand: non-toxic watercolours, pencil crayons, and pens. A tragedy for my Gonzo-journalism practice, but a victory for working towards my own artistic style.

I had the idea to learn watercolours after meeting up with my friend Joolie in Detroit last May. She was on an exuberant multi-state road trip visiting friends to celebrate the easing of COVID-19 travel restrictions and documenting each day’s highlights in drawings that she shared on Instagram. I brought along my acrylic paints so we could hang out and make art together. It was a great bonding experience, but the acrylic tubes were a pain to travel with. Watercolours, on the other hand, are ideal for travel, especially when hardened in pans. I resolved to learn how to use them before my next trip.

I soon leaned into the medium during my 6-week mandatory journalism internship later in the summer. I was averaging 12-hour days between my unpaid internship and the night job I worked to stay afloat. My downtime was almost exclusively spent in bed, but no matter how much I slept, I never felt any less exhausted.

“Sleep and rest are not the same thing, although many of us incorrectly confuse the two,” writes Dr. Saundra Dalton-Smith in an article for TED, one of many I consulted when I began to concede that I was suffering from acute burnout after a grueling first year in my master of journalism program. According to Dalton-Smith, who authored the book Sacred Rest, there are seven types of rest—physical, mental, sensory, creative, emotional, social, and spiritual—and we need all of them “to restore us to the point we feel rested.” Because my watercolour practice was fulfilling multiple rest categories, I kept it up as much as possible during the second year of the program, eventually leading me to Robles’s course.

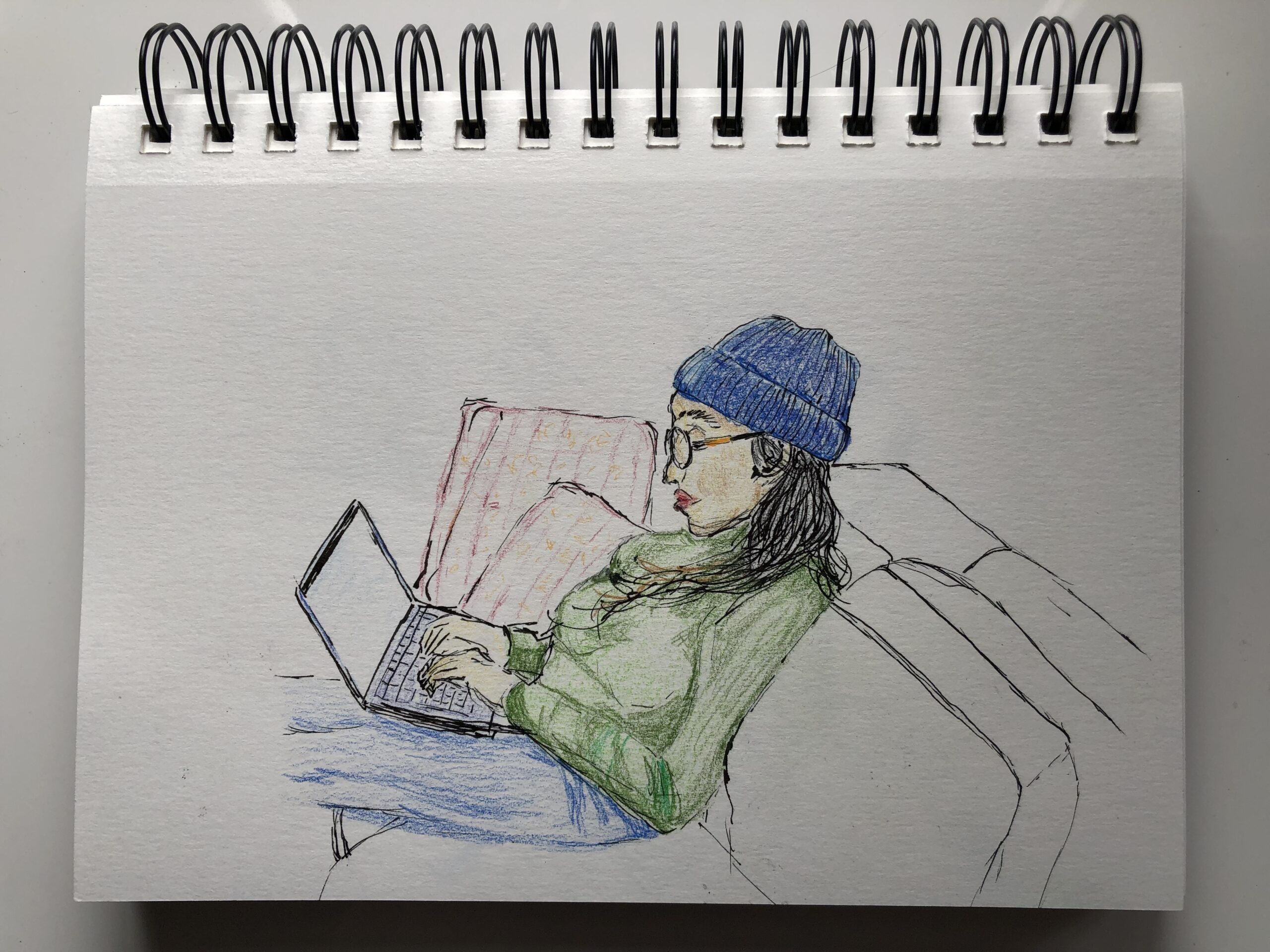

As adults, there’s few experiences as humbling as trying something new. While I’d only felt mildly uncomfortable in the previous units drawing a head, a full-figure, and a building directly in pen, I was not prepared for how mortifying taking on a portrait with a live model would feel. Sitting in an empty Tim Hortons with my parents, I laboured in my sketchbook, trying to quickly capture the essence of my father. I’d asked him to pose thinking it would be less pressure than drawing a friend or classmate; it was not.

“It’s not bad for ten minutes,” Dad said, kindly implying my drawing could have resembled him if only I’d spent five more minutes on it.

“At least you got his earring, so we know it’s him,” Mom added.

I won’t be applying for the role of courtroom illustrator anytime soon. But drawing, like journalism, is a trainable skill. While Robles wasn’t available for an interview to answer my questions—How do you freeze images in your mind so that you can draw them? Why did you create this course? Do you consider yourself a journalist?—I learned that the more you try, the more courageous you become and the more you find your own way. The same lesson that I’m taking away from j-school.

About the author

Leslie Sinclair is a Toronto-based journalist whose primary beats are subculture, the public realm and religion. Passionate about solutions journalism and restorative narrative, Leslie likes to explore themes of identity, social and political action, and everyday life. Her work has appeared in outlets such as Broadview, West End Phoenix, Philanthropist Journal, Spacing and the Globe & Mail. Outside of journalism, you can find her writing memoir or pursuing arts and crafts.