In Inuit culture, Inuk children are often named after a respected community member or relative who has recently died so that their spirit may live on. Once an Inuit child has a name, they have a soul. Traditionally, Inuit families did not share a surname since families were not divided like they are in the South. As nomads in Canada’s North, migrating season to season alongside walrus and caribou, these families did not have a home address, either. The Inuit lifestyle predated the Confederation of Canada by hundreds of years, but Canada didn’t understand it.

In the early 1940s, the federal government began to issue disc numbers known as E-tags (E stood for Eskimo) to Inuit people. Each Inuk was to wear a six-digit number in the form of a tag, like a dog wears a collar, with the number identifying the area, district, community, and family of the individual. Officials had neglected to learn the spelling and pronunciation of each person’s name, complaining that different versions of the same name were too confusing. Tracking was complicated further by the lack of fixed addresses and surnames. In a culture where names held such deep significance, identities were thus reduced to a dehumanizing six digits. No other children in Canada had to respond to a number during roll call, according to journalist Valerie Alia in her 1998 book Names, Numbers, and Northern Policy: Inuit, Project Surname, and the Politics of Identity. It wasn’t until 1969 that the government proposed Project Surname, an effort to consult with the Inuit people to ascertain and standardize the spelling of their names.

If you didn’t know much (or any) of this information, it’s probably because it is not widely included in Canada’s historical narrative. The four regions of the North—Inuvialuit, Nunavik, Nunatsiavut, and Nunavut—make up 35 percent of Canada’s landmass and 50 percent of its shoreline, but they are the part of the country Canadians know least about, according to Falen Johnson. She is one of two hosts and creators of The Secret Life of Canada, a podcast detailing Canada’s under-told histories. Johnson, who is Mohawk and Tuscarora from Six Nations, and her co-host, Leah-Simone Bowen, a first-generation Canadian of Barbadian descent, address Canada’s often troubling, little known past in their makeshift recording studio made out of six blankets draped over two lamps and a divider screen. “You know more about Britney Spears and Justin Timberlake’s relationship than you do about Canada’s North,” Johnson teases Bowen on the podcast’s seventh episode, “The Secret Life of the North.” The same could likely be said of many other Canadians.

Johnson recalls feeling “kind of in pieces” on the day the seventh episode was recorded, just two days after the Tina Fontaine verdict on February 22, 2018. Fontaine was a 15-year-old girl from Sagkeeng First Nation in northern Winnipeg, who went missing in 2014. Her body was pulled from Winnipeg’s Red River wrapped in a duvet cover and weighted down with rocks. Hers was a prominent case in which the jury found the accused, Raymond Cormier, not guilty. Fontaine’s death sparked a number of rallies and vigils and provoked a national inquiry into the cases of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG) throughout the country. Johnson was a day late with the podcast script because she was attending one of these rallies. With both the Colten Boushie murder trial and the Fontaine verdict occurring just weeks apart, she felt conflicted writing about the history of the North—E-tags, dog slaughtering, forced relocation—when Indigenous people were continuing to be targeted. “It’s impossible to not draw the parallels between what’s happened in history and what’s happening now, and how things have changed but not really,” Johnson explains. “It’s the same body. It just has a different face.”

“It’s not a well-known piece of Canadian history, because what’s the better narrative: True North strong and free, or True North strong and slavery before we were free?”

While Canada often promotes itself as a multicultural mecca, communities like those of the Indigenous peoples have had few mainstream platforms to tell their stories. The federal government’s duty to consult Indigenous peoples does not apply to drafting laws, MPs high-five after voting against Indigenous rights, and many Indigenous communities still do not have safe drinking water. Non-white histories have not only been ignored, they have not properly been taught. Marginalized communities have had to work to heal from damaging, overlooked pasts left in the dark. “When we put any kind of racialized or minority group in a position of visibility in the media, that’s important,” says Katie Jensen, the producer of The Secret Life of Canada. “I think that if we’re going to complain about the media landscape in Canada not reflecting its constituents, [then] we have to put changes like this in place and take a chance on new voices.” Enter The Secret Life of Canada’s Bowen and Johnson, two performers and playwrights putting forgotten Canadian history centre stage.

The Secret Life of Canada was born the year of the country’s 150th anniversary. It came out of a pay-what-you-can podcasting workshop hosted by Jensen in 2017 amidst the government encouraging Canadians to celebrate Confederation across the country. Johnson recalls Canada 150 as an outdated montage of stereotypes including mountains, lakes, canoes, and an Indigenous man in full regalia holding an eagle. “But I also think that Canada 150 came with a curiosity,” she says. “There seemed to be people who were willing to accept that Canada wasn’t this picture-perfect place that had been presented to us.” For many, the anniversary was a reminder that the country was built on stolen land and fractured Indigenous nations. “When does a country become a country? When someone signs a paper, or when people are inhabiting that place?” Johnson asks, while Bowen adds, “Or do you want to argue [it was] when everybody got the vote? ’Cause that was in the 1960s.” Because of their background in playwriting, the hosts noticed it had a selective narrative when doing their extensive research on Canadian history. But history is not made up of isolated events. It is all connected. In order to celebrate the great parts of this country, Canada also has to recognize and reconcile the bad.

Jensen was drawn to their podcast idea because she shared the feeling that Canada 150 should have been more balanced. She was refreshed to see The Secret Life of Canada address the country’s history in a way that was not entirely celebratory but did not slander the country either. The trio were able to create the podcast under their “ramshackle blanket fort” in Bowen’s Toronto home with the support of Passport 2017, an app and website that highlighted all events relating to Canada 150. The first season premiered on August 31, 2017, and a year later, The Secret Life of Canada was acquired by CBC Podcasts, allowing Jensen, Bowen, and Johnson to knock down their fort and move into a professional production studio for its second season. The podcast helps push forward CBC’s mandate in that it is distinctly Canadian, and it contributes to “shared national consciousness and identity” and “the exchange of cultural expression.” Johnson and Bowen expected the production process to change significantly after joining CBC, but the corporation remained hands-off. Bowen thinks this is because CBC Radio’s podcast department understands the importance of authenticity of voice in connecting to audiences. When podcasts are too staged or over rehearsed, she says, there is a disconnect with the listeners. Jensen hopes that having a bigger platform will help the podcast reach more rural audiences whose stories aren’t always reflected in metropolitan-centred media.

Podcasts have steadily become more popular in Canada with more than 10 million people listening in 2018, according to the second ever Canadian podcast study, conducted by Ulster Media and Audience Insights Inc. The demographic is made up of mostly men between the ages of 18 and 35, with more listeners having a university degree and a higher income. Jeff Ulster, owner of Ulster Media, says there is an overlap between podcast listeners and early technology adopters, which tends to skew slightly younger and more educated. The hardest part of being a podcaster is developing an audience large enough to sustain your show. “There are lots of marginalized stories and lots of people who are maybe not as easily accessed through mainstream media,” Ulster explains. The challenge, he says, “is you have to go out and find them.” While there are over 550,000 shows on Apple Podcasts, marginalized voices might be harder to find if they are not among the top rated. Moreover, Ulster says that storytellers might not even be aware that their stories can be told through podcasting. That is where pay-what-you-can workshops like Jensen’s can help.

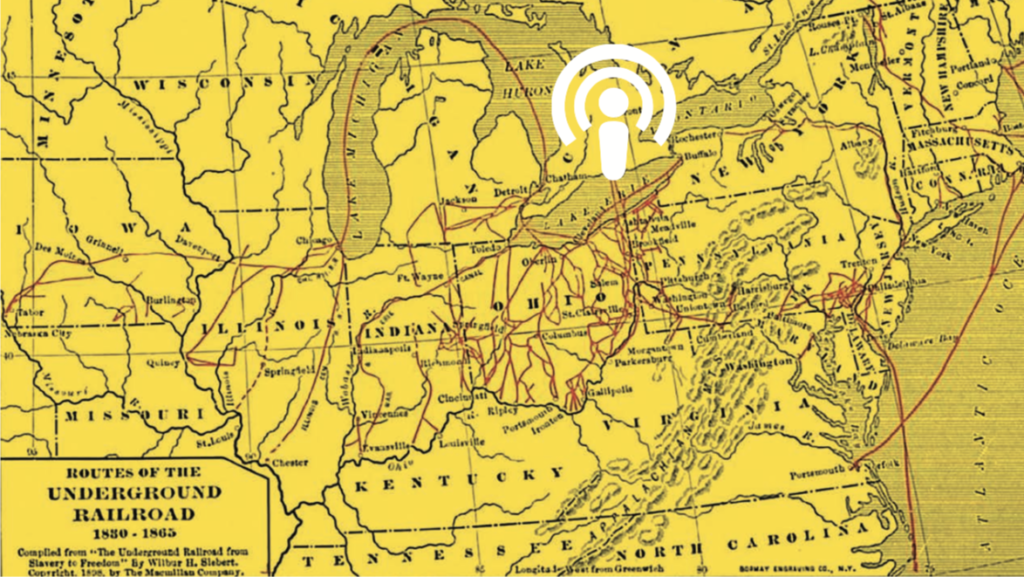

As of March 2019, The Secret Life of Canada has detailed 15 underreported stories and profiled over 17 notable Canadians, such as Fred Sasakamoose, the first Indigenous player in the NHL, and Eleanor Collins, who became the first Black host of a nationally broadcast TV show in North America in 1995. Their 30 to 50-minute episodes have covered everything from the fact that Banff was built by Eastern European prisoners of war to the fact that there were Black slaves on this land for approximately 200 years before the Underground Railroad was established. “It’s not a well-known piece of Canadian history because what’s the better narrative: True North strong and free, or True North strong and slavery before we were free?” Bowen says in the episode titled “The Secret Life of Birchtown.” Charmaine Nelson, an art history professor at McGill University, says in the episode, “The important thing to realize, too, about why we are taught the Underground Railroad is because it feeds directly into this notion that Canada is a nicer, gentler, racially tolerant, or racially blind society. And that’s our myth.” Nelson explains in the “Birchtown” episode that the collective acceptance of this myth did not occur by accident. It is perpetrated through the writing of selective histories and through choosing to exclude unfavourable histories from the public narrative.

“Before the white man came to Canada, Indians ran around without their clothes on,” Johnson’s fifth grade class was told by a substitute teacher on the first day of their “Native Studies” unit. Johnson attended school in Brantford, Ont., and was not the only Indigenous student in the classroom, but she remembers being the only one visibly surprised at the statement. The other students remained blank-faced and did not question the teacher. Johnson wondered if they all knew something she did not. Later that day, she sought an explanation from her dad. He assured her it wasn’t true. Though education has progressed since her elementary school days in the early ’90s, Johnson worries that experiences like hers continue to this day. Bowen also faced knowledge deficits in school when it came to studying non-white history. “Either you’re not learning anything about yourself or your community,” she says, “or you’re learning incorrect things that you know not to be true.” All of the information Johnson and her co-host have shared on The Secret Life of Canada came from research they conducted post-graduation. Bowen doesn’t regret doing the work, but she wishes students could learn in their history classes about more than just the Confederation, the War of 1812, and a few prime ministers. “If you don’t even see yourself visible in the country in the past, you can’t really envision what your future’s going to look like and it makes you feel really disconnected.”

Some efforts have been made to create a more enriched and mandatory Indigenous curriculum in response to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s (TRC) call to action. This includes the introduction of tools like the Indigenous Peoples Atlas of Canada in 2018, but Ontario’s elementary school curriculum still lacks the resources to properly teach Indigenous content in the updated curriculum. The Secret Life of Canada is being used by some teachers as a tool to help fill in the lacunae in outdated history textbooks. Cara McCrae, an elementary school teacher in London, Ont., played several episodes last year for her Grade 6 students, who live about an hour away from Ipperwash Beach. She played the “Secret Life of Ipperwash” episode, knowing it is a popular vacation spot among her students. The episode tells the story of how Indigenous people were forcefully relocated from the land in order to create cottage country, a national park and a military base. McCrae says her students are starting to look at things differently. Though the curriculum has been updated to include more Indigenous content, McCrae does not feel properly equipped to teach it, which is why she has turned to Bowen and Johnson. “I can say that these horrible things happened, but unless there’s something that backs me up, like a textbook or an article or a podcast, I don’t have a lot of credibility,” she says. “And I think that that other side of history has to be shown, because we have some really ugly things that happened in this country.”

Niigaan Sinclair, city columnist for the Winnipeg Free Press, remembers standing alongside his father, Chief Commissioner of the TRC, Justice Murray Sinclair, at a TRC event in Ottawa. As a family, they watched Prime Minister Justin Trudeau (then Liberal leader) participate in a smudging ceremony. He wondered if Trudeau really understood the meaning of smudging. “If you smudge, you would never commit to a pipeline, because what you’re saying is the Earth has value, has power, has strength, and the Earth is a part of me,” he says. “And I don’t know how you reconcile that with pipelines.” The same disconnect applies to Canada’s support of the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) while preserving the Indian Act. “It’s impossible to have those two things,” Sinclair says. “They are completely irreconcilable.”

Canadians do not fully understand the breadth of UNDRIP, according to Sinclair. The document was adopted into the United Nations in 2007, detailing the distinct rights of Indigenous peoples all over the world, including the right to not be forced into assimilation or removal from their land. It addresses Indigenous equality in everything from identity to health to education. The motion had 144 countries vote in favour of adoption while four countries voted against it. Canada was one of those four. It took nine years for Canada to become a supporter of UNDRIP in response to the TRC’s calls to action. Committing to improving Canada’s relationships with Indigenous people is one thing, but it is another thing to truly appreciate why it is necessary.

During Idle No More, a movement that started in 2012 to honour Indigenous sovereignty and protect the environment, Sinclair received phone call after phone call from journalists asking him to explain parts of Indigenous history to them, such as the Indian Act, legacies of residential schools, and Section 35 of the Constitution. “I was doing the work of journalists,” he says. “I can tell you my opinion on the current issue, but my job is not to educate you.” He feels that reporters are confident covering major national news, but there is a level of inadequacy when it comes to Indigenous issues. “Mandatory classes [are] what’s been mandated for teachers and for social workers and for nurses and for doctors,” he explains. “It seems to me there is a demand for competency among journalists.” While Sinclair is Anishinaabe himself and has taught Indigenous Studies at the University of Manitoba for years, he does not consider himself to be a spokesperson. There are hundreds of sovereign Indigenous nations in Canada, each with different cultures, languages, and traditions that differentiate them. These very different groups are often mixed up or lumped together, which is only exacerbated by relying on one Indigenous representative.

As a featured voice on national and international media such as the Guardian, the Winnipeg Free Press, and the Ottawa Citizen, Sinclair has noticed that when he’s invited to address Indigenous issues as a guest, media organizations will also often bring on someone with a racist counterargument. “What I argue, without fail, is that Indigenous peoples are human beings,” he says. “And that when they commit to a treaty or they commit to a relationship with bears or water or the sun, that relationship has value.” In Sinclair’s experience, the debate then diverts from the issue at hand to racism and he is left to defend Indigenous humanity. He adds that it is the responsibility of the media to tell a balanced story, which means deciding who has a platform to speak. Racism is not a valid argument.

“Ignorance is just not an excuse,” Sinclair says. He thinks of journalists as teachers, as their job is to facilitate conversation. “We can’t put everything on journalists, but we also can’t put everything on teachers,” he explains. “But I think expertise is needed at the very building blocks of journalism and education.” Journalism schools across Canada have been called on by the TRC to adopt mandatory Indigenous history classes in order to teach the legacy of residential schools, Indigenous law, UNDRIP, and beyond. The Indigenous Reporters Program created by Journalists for Human Rights (JHR) published a report in early 2019 detailing the accessibility and interest among young Indigenous students in pursuing a journalism career in Ontario. The report revealed that only 31.3 percent of the students surveyed had considered a career in journalism, partially because the field is not often presented as a viable career option, and also because they have few working Indigenous journalists as role models. All of this contributes to the cycle of lost stories and information gaps in the media, a situation The Secret Life of Canada strives to address.

“Once you know that you’ve had a past,” Bowen says, “you can see your future.” Journalism has not represented a wide variety of perspectives throughout history, especially those belonging to Indigenous peoples. Their stories are crucial to understanding Canada’s full history and should be recognized as such. But Johnson and Bowen do not identify with the title of “journalists” for the work they are doing on The Secret Life of Canada. In Johnson’s view, traditional journalists parachute into communities, take the stories they need, and never return. That isn’t what she wants to do. Her view is not unfounded, seeing as journalists have reported on marginalized communities, particularly in Indigenous communities, in this manner for decades. Only recently has it begun to change. Underrepresented voices are growing louder and traditional journalistic practices adapt according to the community being reported in. This is becoming clearer among journalists as guides like Reporting in Indigenous Communities by Ryerson University visiting journalist Duncan McCue begin to surface. Indigenous podcast creators like Canadaland’s Ryan McMahon and CBC’s Connie Walker tell stories of injustice and discrimination by first building foundations of trust in Indigenous communities. The Secret Life of Canada is a herald for this approach to storytelling as well. “We want to really have community members tell their historical stories, the stories of their ancestors, the stories of their parents and grandparents,” Johnson explains, “and to do that, I think you have to make a connection.” There are systematic reasons why certain people thrive while others struggle, and the media needs to account for the history connected to the oppression that continues today in order to strive for a more equal tomorrow.