Canadian gaming journalism remains sparse despite the best efforts of key players in newsrooms

It’s December 7, 2023. The 10th Game Awards show to be hosted by Geoff Keighley is held at its usual venue: the Peacock Theatre in Los Angeles, California—happening live in LA, and live streamed on YouTube and Twitch, among other platforms, reaching a peak viewership of over 118 million global livestreams.

Winners of awards such as best narrative and the coveted Game of the Year receive an opulent statue: metallic grey, it depicts an angel spreading its wings outward. Its cubic and blocky texture resembles pixels, and the angel’s form is reminiscent of wire-frame models used in game design. It is deceptively light, with many award winners first attempting to carry it with one hand before immediately needing the other.

The annual awards show is a celebration of gaming’s accomplishments and a salute to excellence in the global video game industry. Lining the seats are influential figures from the industry, from popular content creators and the nominated developers to executives from multibillion-dollar companies such as Nintendo. All are united, however, with shared blank expressions and polite laughter as they watch Keighley awkwardly make gaming jokes and jarring segues into game trailers, sponsors, and awards for the rest of the main show’s three-hour run time.

Despite the show’s overstuffed lineup, my friends and I love watching it because there really isn’t anything like it. The awkward atmosphere is endearing. But something feels off this year.

Award winners barely have time to finish their speeches. “Please wrap it up,” a teleprompter tells them when they go over 30 seconds. Keighley seems to rush through the accolades; at one point, he reveals the winners of four prestigious awards in a span of a minute and 20 seconds. Meanwhile, most of the run time is dedicated to advertisements: Hideo Kojima of Metal Gear Solid is given eight minutes to promote his collaboration with Jordan Peele for his new game, OD—without a single frame of gameplay footage.

The uneven focus on advertising future games over celebrating achievements is obvious enough. But perhaps the most egregious omission of this year’s Game Awards show is that it didn’t address one simple fact: 2023 was a great year for games, but one of the worst for the industry.

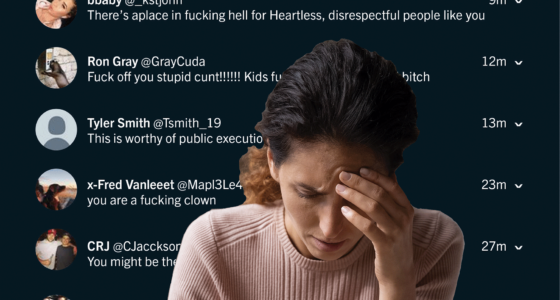

Companies like Bungie, Electronic Arts, and Epic Games laid off thousands of employees collectively last year. A week before the show, a group of more than 70 recipients had pushed for a statement to be read at the awards denouncing the ongoing genocide in Gaza, and criticizing the industry for “systematically produc[ing] works that dehumanize and vilify Muslims, Arabs, and the many brown and black people.”

As for its jury, the Game Awards roster is composed of over “100 leading media and influencer outlets across the globe.” For the U.S. it has a staggering 25 media representatives. Canada has only four: CBC, CGMagazine, Le Journal de Montréal, and Screen Rant—a movie and news website that, although now based in Montreal, was founded by an American in 2003.

Bradly Shankar, a Canadian journalist with MobileSyrup, who was present at the show, criticized the Game Awards’ “paltry representation” of Canada’s industry. “Why aren’t we representing ourselves on the global stage?” he wrote in an article for MobileSyrup, clarifying that while he likes these sites, the Canadian representation is still far too sparse. Patrick O’Rourke, MobileSyrup’s editor-in-chief, expressed a similar concern: given the impact games developed in Canada have on the global industry, why not have actual Canadians on the jury?

Indeed, it seems the last time Canada’s gaming coverage kept up with its industry was in 1995, when Electric Playground (now EP Daily) launched. The field was ever-growing, and the show was a glimpse into its intense, fast-paced world.

At an event featured in season six of Electric Playground, guests on the show were shouting over the game showcases and the bustle of the attendees. The show’s intros resembled what was happening in gaming at the time, with clips of games new and old gliding across the screen. EP Daily could very well function as a time capsule of the early 2000s gaming culture.

Still, gaming has steadily grown since then. According to a 2021 report from the Entertainment Software Association of Canada, the video game industry contributes $5.5 billion to Canada’s GDP. ESAC reports that as of 2021 a total of 937 video game studios operated in Canada, with the equivalent of 32,300 full-time employees. On the consumer side, 23 million Canadians are considered gamers—whether they play Elden Ring on a heavy-duty gaming PC or swipe through the occasional game of Candy Crush Saga on their phones.

When I compare old episodes of EP Daily with last year’s Game Awards show, it’s clear to me that the excitement about the gaming industry itself has waned further in favour of product placement. When EP Daily went on hiatus in 2015, it felt as though no show could ever replace it. CGMagazine formed in 2010, but it wasn’t Canadian-centred. Without another show like EP Daily, which was marketed directly to those interested in gaming and tech, and given that the U.S. has a stronger foundation for gaming coverage, it isn’t surprising that people would turn to for gaming news.

As active gaming coverage in Canada continues to plateau, the challenge today is figuring out how to boot it up again. But that doesn’t mean players haven’t tried picking up the controller.

The Canadian grind

Canada’s contributions to the gaming industry have placed us near the top of the global leaderboards: In 2012, Canada rose to become the world’s third-largest producer of games, according to ESAC. We are responsible for some of the most popular franchises in the industry, including triple-A (gaming lingo for high-budget, high-profile games) titles Mass Effect and Assassin’s Creed. Canadian indie games titles landed in the mainstream with the notoriously difficult Darkest Dungeon and Cuphead, a run-and-gun game animated in a style reminiscent of early Walt Disney animations.

But covering Canada’s extensive gaming development history and present remains a challenge. Many of the biggest publications for all things gaming—IGN, Kotaku, and Gamespot—are based outside of Canada. An effective publication would have to be able to compete with these giants and also celebrate the Canadians who work in it.

“You can be the afterthought if you’re labelled as a Canadian piece of content, especially when you’re compared with the U.S. websites”

Enter MobileSyrup, created 17 years ago. “[The website] was very focused on telecom, carriers and smartphones,” says O’Rourke. “Since then, we expanded to cover everything in the tech space, with a Canadian angle.” Through SyrupArcade, its dedicated gaming section, he says MobileSyrup and its writers have freedom to publish whatever they want. “We’re also a blog at the same time. So if you’re writing a news story and want to add a dash of opinion to it or just write a straight-up editorial…that’s okay.”

But O’Rourke says its identity as a Canadian news site creates unique challenges. “Sometimes, you end up being the afterthought when you get labelled as a Canadian piece of content, especially when you’re in some ways competing with U.S. websites.” He says while many companies provide excellent access, some seemed not to care about Canada.

MobileSyrup struggled to get review codes or press releases from certain publishers. O’Rourke mentions it is likely that some of these publishers simply didn’t have a dedicated Canadian PR wing. But for the times when publishers do reach out, MobileSyrup ensures they cover the story with a Canadian perspective.

Behind the cutscenes

It’s late 2023. Shankar, gaming editor at MobileSyrup, prepares to interview Thierry Boulanger, the president and creative director of Sabotage Studio, an indie-game studio in Quebec City known for creating the action role-playing game Sea of Stars. It’s the culmination of the relationship he’s developed with Tinsley PR, an American video game and tech entertainment consulting company, which has been his way in for the video game publishers it represents, like Deep Silver and Quebec City-based studios like Chainsawesome Games. Not long before, the PR group had set up an interview with Awaceb, the developers of Tchia, a game nominated at the Game Awards “for a thought-provoking game with a pro-social meaning or message.”

Still, even as Tinsley connects him with another Canadian developer, Shankar is surprised at its consideration: it was rare in this space for Canada to be given specific notice in this way. Even outside of gaming-specific events, he’s been lumped with Latin America. “I was at the Meta Connect event, and I was the only Canadian there,” he says, recalling sharing his section with six media representatives from Mexico, Brazil, and Argentina.

As Shankar and Boulanger begin their Zoom call, Boulanger acts as he normally does with gaming journalists: polite, friendly, giving well-thought-out answers he’s provided before. The game’s clear inspiration from the 1995 role-playing game Chrono Trigger and the fact the game’s music was created by the same composer for Chrono Trigger are just the biggest elephants in the room. “Everyone’s gonna ask him about that,” Shankar tells me.

It isn’t until Shankar points out the little nuances a Canadian would appreciate in Sea of Stars that Boulanger “would light up even more and get excited,” leading to a tangent from Boulanger about all the other details he hopes Canadians can appreciate in Sabotage Studio’s game. “To have a wider variety of people speaking to developers, you’re gonna ask different questions, get different answers. It’s better for everyone when you have a greater diversity of people in gaming coverage.”

It’s a game made by Canadians developers; why wouldn’t you have Canadians interview them? The answer is a more fundamental question: Who, exactly, is even interested in hearing the Canadian perspective?

Critical complaints

This question plays out in how gaming stories are discussed and assigned in newsrooms across the country.

Jonathan Ore, a writer and editor for the CBC Radio digital team in Toronto, semi-regularly reports on the video game industry. He describes a challenge he encountered when he covered video games with the CBC News entertainment unit, whose writers typically follow films and television. “The people who were working there were more used to the rhythm of covering TV and movies in that industry,” explains Ore, who has been at CBC for over 10 years. Initially, he says, “they kinda thought the gaming industry was very similar.”

But it wasn’t. For instance, it is very challenging to book certain people to interview. It isn’t clear who the face of a game is, unlike a movie’s director or lead actors. While you might recognize Cameron Monaghan—or as my family calls him, the guy who played Joker in the Gotham TV series—as the voice of Cal Kestis in Star Wars Jedi: Survivor, you typically won’t see the game’s creative director plastered on billboards and commercials. (His name is Stig Asmussen, by the way.) And even if you do find that creative director, what they’ll tell you may not be exactly what you want to hear. These interviews are often more akin to press releases from tech companies. Ore says the answers tend to be predictable, and very surface level. But, in his opinion, “It’s not going to be a candid, ‘late-night-show’ couch conversation as you would for TV.”

The idea that video games are nothing more than just another way to pass the time also bleeds into assumptions of the time required to produce thorough coverage of them. One journalist I spoke to shared how an editor reached out to him to play and review Cyberpunk 2077—a title with over 100 hours of gameplay—two days ahead of its release.

Another issue at the time, Ore says, is the assumption that game developers would even want to talk to CBC or any news publications. “In the years since magazines declined in importance, game companies realized they could just make their own trailers and promote themselves on social media,” he says, adding that this coincided with the rise of YouTube as a reliable way to garner attention. If anything, it is up to the journalists to understand how the industry works if they wanted to effectively cover it.

Ore shared how Ubisoft once invited him to a “secret game reveal” in 2017, seeking him out as a Canadian journalist who covers the game industries as a beat. His coworker, who had been in the news department longer than Ore, asked, “Do we know if there’s going to be, like, a Johnny Depp-level star who is gonna be there?” Ore’s editors echoed the same concern, and Ore had to explain he had received no details pertaining to the presentation—nothing about who would appear in the show or even about what kind of game would be revealed.

Ore didn’t always have a clear grasp of his editors’ reactions at the time, but the lack of information frequently exasperated them. With a film premiere, Ore says, “You’d probably get some idea of what the hell you’re even seeing and who’s even going to be there.” Ultimately, the additional travel and accommodation costs to send Ore to Montreal were not approved. So he suggested a CBC Montreal reporter cover it instead.

Ubisoft rejected CBC’s proposals, says Ore, who recalls the company mentioning that the invitation was not able to be transferred. But Ore still wishes he had gone—the “secret game reveal” turned out to be for Ubisoft’s Far Cry 5, the 2018 instalment of the series of story-driven first-person shooter games. It became the franchise’s fastest-selling game, with launch sales exceeding $310 million (U.S.).

“It was a bit of a culture change,” he says, referring to the difference between coverage of video games and other forms of entertainment. “You don’t really get to request who you want to talk to in the gaming industry. Like, I would love to talk to the specific person who wrote my favourite part in a game, only to be provided with the quest designer or narrative director, or some nebulous producer-level job.”

It’s much harder to find specific people to interview in games rather than in television. As Ore mentioned before, there isn’t a big pool of big name “celebrities” in the industry, as opposed to in film. But now, even if you do find one, are they fascinating for people who don’t necessarily play video games, let alone recognizable by those who do?

Certain issues persist, Ore says, with some people still believing video games are just simple distractions made, sold, and advertised as toys. He recalls a time when he felt like editors and senior producers would check out upon hearing the words “video games.” It would be better for other sections on CBC, they’d tell him. It can be hard at times, since many big games are made outside of Canada, which makes it more difficult for there to be a Canadian angle.

He uses Taylor Swift as an example. She’s not Canadian, and while some of her followers are children, fans of all ages listen to her music. A Taylor Swift story could be approached in myriad ways—as music industry news, celebrity news, a cultural phenomenon, or business news.

“When you’re 25, you might think, ‘Oh, this is cool.’ When you’re 35 you’ll realize there’s no version of this where I can just do this and get paid for it”

“But if you just saw that as a kids story,” Ore explains, “that feels like you’re really limiting one’s perspective as to the reach and significance of what that means. Can people spend the time to recognize that [gaming] is a part of our culture and our world, having connections and implications that we might not have thought about?”

Experienced points

Launched in 2012, the Post Arcade is one example of how a dedicated gaming section existed within a larger publication. It began as a passion project led by Matt Hartley, former editor of the Financial Post’s Tech Desk, when he noticed a potential crossover between gamers and readers of the Tech Desk.

Daniel Kaszor, who started at the National Post as a copy editor in 2008, began to contribute a weekly column to the section on top of his regular duties in 2011 . Post Arcade “becomes your evening job you’re doing for free,” Kaszor remembers. On his experience at Post Media, he says, “When you’re 25, you might think when you’re writing for free, “‘Oh, this is cool.’” But, he continues, “When you’re 35 you’ll realize there’s no version of this where I can just do this and get paid for it.’”

Hartley was the closest to realizing that “version,” Kaszor explains. Hartley wanted to attract advertisers to grow Post Arcade. He, Kaszor, and several other journalists at the Post would transfer their attention to Post Arcade. It “would be Canadian Gizmodo. It will be Eurogamer, but Canada.”

This argument was bolstered by some key successes. One of Post Arcade’s biggest stories was Future Shop’s 2013 promotion fiasco. The electronics chain allowed customers to trade any used Xbox 360, PlayStation 3, or Wii U game for a copy of the newly released Call of Duty: Ghosts, Battlefield 4, or Assassin’s Creed IV, free of charge. It doesn’t take much to understand why it was a losing proposition.

Chad Sapieha, now one of the last remaining writers for Post Arcade, remembers the traction of that Future Shop story. “It became one of the biggest stories in the entire newspaper for that month. And if you get enough of those, I think you’ll start to make an argument for the number of hits you can generate just from a purely game-focused story.” But Sapieha says the issue is that you can’t guarantee a “purely Canadian” story that “hits all the boxes for an editor” every month.

It was for these reasons that Sapieha wrote many stories focused on Ubisoft Toronto for 10 years. Why wouldn’t he? The obvious Canadian angle allowed him to report on everything from government injections and tax breaks to its impact on the game development industry in Ontario. It was a gold mine in terms of being relevant to both gamers and the business world.

Sapieha felt that engagement from the audience was far from consistent. Years prior, he blogged as the “Controller Freak” for The Globe and Mail’s gaming column. “Some got almost no hits at all,” he remembers. People don’t necessarily go to a national newspaper for video game coverage. Six or seven years after Post Arcade launched, Sapieha says the Post gradually cut back on its gaming coverage as overall resources dwindled. “It’s still going. I’m still passionate about it. But it’s not quite as big as it once was.”

By 2014, Sapieha and Kaszor were among a handful of people who remained at Post Arcade. “We still get to, y’know, cover the big games and do interviews and stuff like that, which makes me happy,” says Sapieha. Hartley left after two and half years, with plans for a career change. Although there were talks of expanding Post Arcade, “It just got delayed and delayed and delayed,” says Kaszor.

Kaszor then took on Hartley’s role as the editor. As the media landscape shifted, the section became composed mainly of work by Kaszor and a gaggle of freelance writers, some of whom were very new to journalism. Rather than filling seats with younger, more diverse voices with a fresh perspective on Canada’s gaming industry, the number of jobs shrank. The reason was simple: there were no resources.

So Kaszor would devote his free time to Post Arcade, and accept work of people who were willing to write reviews even if he couldn’t pay them. He stresses that if he could go back in time, he would not accept these journalists’ work for free. But as he received their offers to complete work in exchange for exposure, he remembers thinking at the time: “That’s kinda bullshit but, y’know, I’m an idiot who just started working here. Deal!”

Kaszor hoped that when the site gained traction he would be able to pay the freelancers, and the free reviews would help get them there. Meanwhile, the people pitching him would gain exposure by simply writing about a hobby they loved. “He might be describing me,” Ore says. He knew Kaszor as a fellow student a year ahead of him at Toronto Metropolitan University, and did in fact approach him after graduation to write reviews for him.

But by the third or fourth time, Kaszor says, some writers found that the value was fully diminished. Besides exposure, he says, “You’re not giving them a reason to keep writing.” He couldn’t keep asking freelancers to write for him only to reveal there were no spots for them on Post Arcade. Not because he would reject them—but because writers weren’t hired exclusively for Post Arcade to begin with.

Game over. Play again?

Two thousand and twenty-three was a tough year for both the video game industry and Canadian journalism. Both experienced massive cuts, amounting to thousands of people laid off. As jobs in Canadian media continue to shrink, the future of gaming journalism in Canada can appear especially grim. Only a few days into 2024, more than 2,300 people had been laid off in the gaming industry as a whole, following a trend of the hundreds of layoffs last year in the Canadian video game world. Coverage of the industry, as with any other, is essential. But questions remain as to whether gamers would bother to read Canadian coverage on video games, and if traditional journalism is even the best way to do so.

Even as I wrote this feature—speaking with gaming journalists and realizing how difficult it is to come up with gaming puns—there was always this persistent feeling that no one would actually care. I doubted if this piece about video games even belonged in this magazine. Would journalists even care to read about it? Would gamers care about behind-the-scenes stories when they barely watch anything besides walkthroughs and guides?

“The older I get, the more removed I become from the community of game journalists,” says Sapieha, who has been writing for more than 25 years. He recalls when O’Rourke called himself, with his tongue planted firmly in his cheek, one of the oldest game and tech journalists in Canada. “Even though he’s only in his early 30s, he’s not wrong. Because most people who do this gig realize there’s almost no money for it in Canada.” Many end up in public relations or working within the gaming industry itself. “All these different people who’ve taken these different routes to stay within games or within technology,” says Sapieha, “they’ve just given up on the journalism side of things.”

But despite the bleak reality of the industry, there are moments that remind him that his work with Post Arcade has an impact. He describes a chance encounter with a fan at a Toronto mall. “Somebody just recognized me and said, ‘Hey, you’re the Post Arcade guy. I love your stuff, man.’”

A meeting at a mall isn’t a sign that Canadian gaming journalism is saved. Still, it does leave some hope that there are people out there who are willing to listen. You just have to know what they want.

While that’s obviously easier said than done, every game’s success is always based on the number of people who still play it. And there are definitely enough players willing to try something new.