Wildfires, standoffs, and arrests: Inside the terrifying, underpaid lives of Canadian photojournalists

Photojournalist Jen Osborne got out of the car, head to toe in personal protective equipment. She had researched what she needed to wear to shoot a megafire in Australia and bought cheap versions of the required safety equipment. It was her first time covering a wildfire, January 2020. Everything around her looked red and hazy. The fire was jumping from tree to tree. Flames shimmered across the horizon, flickering in the smoky red sky. This looks like hell, she thought. And yet, she was mesmerized. “The weird thing about fire,” she said from Australia while covering the wildfire season there this past November, “it’s terrifying but stunningly beautiful.” That was when she fell in love with wildfire photojournalism. She decided to dedicate her personal practice to this specialty.

Osborne studied fire behaviour and enrolled in safety training to learn how to navigate a fire zone. At one time, many photojournalists like Osborne were employed by newsrooms, earning salaries and benefits, and getting support from their bureaus. But around 15 years ago, amid budget crunches during the Great Recession, 2007–09, Canadian newsrooms began to shed staff photojournalists to the point where, today, most working photojournalists are freelancers, underpaid and undersupported. They go to great lengths to do their work, but their dedication comes at a huge cost.

Being a freelance wildfire photojournalist involves long hours, incurring travel, board, and food costs along the way. “I’m going to keep doing this for as long as I can afford to do it and not go completely bankrupt,” says Osborne. Half the time, she is working on spec, meaning newsrooms rarely send her out on assignment. She shoots with no guarantee that clients will buy her photos. To do what she loves, Osborne has adjusted her lifestyle. She doesn’t own a house or condo, doesn’t have extended medical insurance or a pension plan. To date, her highest annual income has been $50,000 after tax, and there have been years when she made $12,000. “I’ve usually just had cheap rent those years, like $500 a month,” says Osborne. “You just have to rough it.”

In 2020, the United Photojournalists of Canada (UPOC) conducted an anonymous survey of professionals in the field. Of the 80 respondents, 79 percent said existing rates in photojournalism were unsustainable; 69 percent reported making under $50,000 per year; just over half reported making under $40,000 per year; and about a quarter reported making under $30,000 per year. The totals include income from photojournalism and other sources, as most freelancers need other jobs to support themselves.

To Osborne, the highest price she pays as a photojournalist is psychological. She’s not alone: according to UPOC’s survey, 72 percent of respondents said working as a freelancer had negatively affected their mental health. Like other frontline workers, including police, firefighters, and paramedics, photojournalists often experience various traumas on the job. And because they spend so much time on the road, especially those who work on international stories, they often can’t draw on support systems. Most newsrooms and publications do not provide any mental health or trauma-informed support for freelance photojournalists. And given their low incomes, most photojournalists can’t afford mental health services. Osborne says she’s seen people turn to substance abuse because of their feelings of isolation, but it depends on the amount of support. “A stable household, with a good marriage, good family, good family dynamics, good friendships, consistency,” says Osborne, “those help prevent people from falling off the deep end.”

Poor mental health can negatively affect anyone, but there can be unique struggles for women. In 2022, Osborne worked with Coulson Aviation, a private aerial firefighting company based out of British Columbia. She says a lot of the male helicopter pilots she worked with would be away from home for half the year, yet many had partners who were willing to wait for them. In Osborne’s personal experience, women on the road may struggle to find understanding partners. While covering wildfires in Australia, she observed that men have an easier time getting into fire zones because they can create a natural rapport with predominantly male firefighters.

But getting into spaces that few others see is what keeps Osborne going. In 2021, she covered the Fairy Creek blockade on Vancouver Island, the largest act of civil disobedience in British Columbia’s history. Land defenders—activists working to protect ecosystems—had been protesting the logging of old-growth trees in Fairy Creek, near Port Renfrew. There was a heavy police presence. An injunction sought by Teal-Cedar led to protestors being arrested.

During the three months Osborne covered the blockade, she rented a room nearby, and also spent many nights sleeping in her car or on an emergency blanket on the gravel. She tried to maintain a low profile and remain neutral, fearing she would attract loggers who might damage her vehicle. The land defenders themselves were wary because they didn’t trust the media. “It was hard to report on that without stepping on the toes of the land defenders,” says Osborne. “You need to keep access with the protestors because they let you into their blockades.” The police created exclusion zones to prevent protesters or reporters from going into the area being logged. Though Osborne had been friendly enough with the police for months, they refused to allow her through. After having a verbal standoff with police officers about getting into the exclusion zone, someone from the crowd defended her right to report, and the police finally let her through. They wouldn’t let Osborne bring her vehicle, so she had to run a few kilometres up to the base camp, only to miss the enforcement at the top of the hill.

During one of her final reporting days, when she was shooting at the main highway on Fairy Creek, the RCMP pepper-sprayed the land defenders. “I was the only professional photojournalist there that day,” says Osborne. “I was raising attention for the hardship the protesters were experiencing on the day when the pepper spray happened.” A few protestors who saw the images were upset with her for taking photographs without their consent, she recalls. The photograph that was published was a group shot of the protestors and land defenders, and given the perceived newsworthiness of what had occurred, Osborne did not ask for permission. She says that photojournalists fend for themselves—with or without newsroom backing—when their work is heavily scrutinized by the public (despite their work being for the public).

Osborne has been working in the journalism business for 23 years, yet only recently began to learn how to ensure her own needs are met—how to debrief after an assignment, for instance, and take care of her mental health. She doesn’t see the industry providing mental health coverage to freelancers anytime soon, so, instead, she has applied for various grants. She recently received one for 14 psychotherapy sessions from the Rory Peck Trust, which provides financial aid to freelance journalists worldwide. The best way forward in her field, she believes, is for freelance photojournalists to support one another. “I see a lot of competitive bullshit happening between photographers,” she says. “They’re all fighting for scraps, right? They’re all fighting for these small jobs. We’re all living in poverty. It’s deeply competitive. But I think people need to work together to be supportive because we’re the only ones who can really understand what each other goes through.”

It had been a day or two since a wildfire almost burned down a fishing lodge south of Vanderhoof, B.C. Fire crews had gone to the scene with structure-protection equipment and saved the lodge from intense wildfire. In mid-July 2023, Jesse Winter, along with one videographer, had driven down to capture the aftermath. On a long, narrow road through a burn area—still smouldering from the fire—the videographer appeared to be on edge.

What is the risk? What am I missing? Winter thought to himself. The risk, the videographer said, was that they didn’t have a chainsaw. The trees that had been burned could easily fall over and hit them or block the road. They drove toward the fishing lodge and, as agreed, were in and out in 35 minutes.

Last summer, when the wildfires began in B.C., Winter requested to cover them on assignment for publications with which he’d previously worked. He had completed safety training and bought PPE such as fire-resistant clothing. He had an agreement with the B.C. Wildfire Service granting access to the fire zones and crew, yet the publications declined to assign him stories because, generally, it’s difficult to get into fire zones.

Winter says a lot of stories are going uncovered or underreported because photojournalists and other reporters aren’t guaranteed access. “If we can build better, more clear and straightforward access for journalists into the spaces where it becomes clear that we are first responders,” says Winter, “we could go into these places, figure out what’s happening, verify it and report it back to the public.” Modern wildfires are, in part, the consequence of climate change, yet many Canadians do not necessarily understand that because there’s so little access to cover wildfires. In the past, there have been fires in B.C. that impacted the community, which were followed by allegations that they were not natural fires, but planned ignitions gone wrong. Winter experienced this in 2021 during the White Rock Lake wildfire, which destroyed 83,000 hectares and damaged over 100 homes in communities from Monte Lake to Killiney Beach. Largely due to the difficulty in getting press access, says Winter, there was very little independent verification of what wildfire services and emergency responders did to address that fire. The emergency responders and wildfire services were on site and actively working, but a narrative formed that the firefighters weren’t doing anything to help the community. Amid these accusations, there was an investigation into the B.C. Wildfire Service. Freedom of Information requests were made to uncover the documentation of how it addressed the wildfires. Many of these allegations could be cleared up if transparent access to fire services existed so that the public knew what had actually happened, says Winter. “Maybe there are planned ignitions done wrong, maybe not,” he says. “If it is true, we need to be able to see it, talk about it, and publicly explain why.”

Winter decided to cover the wildfires without an official assignment. “I went on my own with a plan to go out with the fire crews, get some pictures, provided that I had access,” he says, “and then start pitching again.” He spent a week and a half on the road, putting himself financially at risk, in part by turning down other, unrelated assignments.

But even when publications eventually bought his photos, Winter says, they were hesitant to cover expenses. “They were happy to put me on an assignment for a day or two, but reluctant to pay the mileage costs,” he says. He ended up splitting the costs among all his clients. There was a lot of appetite from publications to buy his material, so he made enough money for the shoot to have been worth the risk, but it “speaks to the frustration I often experience with the amount of support for photojournalism in Canada.”

Gaining access to wildfires and entering fire zones is tricky because photojournalists must request access from wildfire services. According to the B.C. Wildfire Service, while photojournalists are not required to complete safety training, PPE may be required for access to some areas to ensure the safety of all personnel on-site. In order to gain access to the wildfires, photojournalists such as Winter complete fire safety training and prove they have equipment such as fire-resistant clothing—without newsroom backing. “We’re expected to get the access—the fight lands on our shoulders,” says Winter. “It’s so easy for publications to offload responsibility for all of that onto us.” Beyond expenses for individual shoots, photojournalists buy and maintain all their camera equipment, which amounts to thousands of dollars a year. If the equipment is damaged while on assignment, or malfunctions, the client is not obligated to cover costs. Winter says this wouldn’t be as much of an imposition if photojournalists were compensated fairly for their work and time.

When newsrooms laid off most photojournalists—except for those on salary with “reporter” in their title—they did it to save money, says Winter. He says photojournalists are one of the most expensive staff to employ. According to UPOC’s survey of photojournalists in the field, most freelancers are paid significantly less than a livable income. “As though this isn’t a negotiation,” says Winter, “as though newsrooms have the exclusive right to set their rates and we just have to accept whatever rate that they want.”

One editor listened. Matt Frehner, head of visual journalism at The Globe and Mail, advocated revising the company’s contracts for photojournalists and, in 2020, a collection of Canadian photojournalists (who later banded together as UPOC) and the Globe had a discussion. The photojournalists raised concerns over contract language, copyright, distribution terms, and rates—which hadn’t been substantially increased in years. “We were able to work with the company and get approval from the company to increase the rates,” says Frehner. The Globe not only increased payments, it also increased the freelance photojournalist budget as part of this discussion, he says.

“That’s the scary thing about being independent.

You hope that outlet would support you, but have

no guarantee” — AMBER BRACKEN

Ultimately, the Globe raised its rates by about 20 percent, which Frehner said accounted for 20 years of inflation. “We’re very thankful for it, and it set a high bar,” Winter says. “Other publications followed suit.” According to Winter, “The Narwhal and Canada’s National Observer both agreed to up their rates to match the Globe’s.

The extra money is nice, but travel is too expensive to have photojournalists based in Toronto, says Frehner. It made sense for the Globe to develop a freelance network, because the geographical advantage provides diversified coverage. “If we want to cover something in the North, there’s Pat Kane,” says Frehner. “If we want to cover something in Edmonton, there’s Amber Bracken. If we want to cover something on the East Coast, there’s Darren Calabrese.” This flexibility is crucial in an era of shrinking newsrooms and budgets. “Would I love to hire 10 staff photographers? Yeah, I would,” says Frehner. “But you have to justify the expense.”

When Toronto-based photojournalist Cole Burston went to Shuswap Lake region last August, what started as a shoot quickly turned into an on-the-ground mission to help put out fires. On his first day, a local told him to hop on his boat and sail down the lake to help take an evacuated community back home. “I said it would be great to show people what’s actually happening because we [photojournalists] usually aren’t really allowed in,” he says. He took photographs as the boat motored through the thick orange glow. It was often hard to see around him. The boat made it through and dropped off evacuees at various locations. After a long day, they approached one of the final drop-off spots, one where Burston had also planned to get off. On the shore, he turned to the person on the boat and asked to stay the rest of the day and join them. “This was such a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.”

They dropped him at a location near a small fire. He had done basic theoretical training for wildfires, but had no experience with firefighting. He heard someone yell that since he was staying, he might as well work the water pump. Burston helped unroll the hose. He looked up and saw flames coming up out of the trees, the sky radiating smoky orange. He was surrounded by burned houses, many still smouldering. “At that point, I put my camera down,” he says, “and helped this guy.” Burston went with the fire crew to help put out small fires the rest of the day.

The next day, he went back to take more photographs. A police officer picked him up. He was dropped off outside the evacuation zone, which he had to walk through. He could barely see 50 metres in front of him. “I have never seen smoke this thick,” he says. “My eyes were burning, and I was having trouble breathing.” He pulled an extra T-shirt from his bag to create a scarf for his face.

Burston had not bought any PPE for the trip. Due to the pressure from clients, he had reduced his expenses. “We’re told to make the editor’s job easy, and that’s how you’ll get work,” he says. Past clients have even asked him to rent a cheaper car. He didn’t want to risk being turned down for this assignment, which had already been a quick decision, so PPE expenses weren’t on his radar. Although newsrooms typically cover expenses, many photojournalists might not get these assignments due to PPE costs and other charges.

The boat, owned and operated by an area resident, sailed north from Sorrento boat launch to Scotch Creek, on the north shore of Shuswap Lake. Ben Nelms took photographs of evacuees they were picking up from the small community, located just west of Shuswap Provincial Park. They then headed to Celista, B.C., to pick up one family. Nelms continued taking photographs. After dropping off the family, the man who owned the boat wanted to check on his place in Scotch Creek, so they docked the boat and walked into the community while surrounded by smoke. “It was the middle of the day, but it looked like dusk because the smoke was so heavy,” says Nelms. As he walked, he noticed power lines on the ground and burning houses. He was with people who had lost everything. Some walked with a single bag over their shoulders. It was all they could take with them, so it was all they had left. “It’s such a traumatic experience for them,” says Nelms. “They forget you’re there.”

Nelms didn’t want to make his presence felt, or else, he thought, the police would have had him removed. He also didn’t want to disturb people who were mourning their losses. He quietly captured photos of the harsh reality before heading back to the boat. By 3 p.m., on what would normally be a bright, sunny August afternoon, it was dark. They began the sail back to the marina but could not see in front of them and had to circle back to Scotch Creek. That was when they realized they had no GPS and no idea where they were. They were very concerned. “Luckily,” says Nelms, “I had one bar on Google Maps.” After 45 minutes, they hit land and returned to the Sorrento boat launch. Nelms walked toward the parking lot, found his car, filed his story from there, and drove back home.

After 10 years of freelancing, Nelms joined CBC in Vancouver in 2019 as part of a six-month pilot program to hire full-time photojournalists for online news. After the program ended, he stayed on as staff. No more selling images to a newsroom or rate negotiations. He uses CBC equipment now. When it stinks of smoke after he photographs wildfires or sustains any other damage, the company covers the repairs.

The biggest difference between freelancers and staffers is the job security. “Freelancing is stressful,” says Nelms. “You’re either working every day and turning down jobs, or there could be weeks at a time when the phone doesn’t ring.” As a staff photographer, he has more job security, a steady paycheck, access to programs such as hostile environment training courses—and less anxiety.

Nelms doesn’t see the industry hiring more photojournalists anytime soon. They’re often underappreciated because of a lack of awareness of how difficult and nuanced their jobs really are. “When I was covering the wildfires, 95 percent of the week was driving, trying to find access, viewpoints, talking to people, and doing all that,” he says. “Only five percent is actually shooting.”

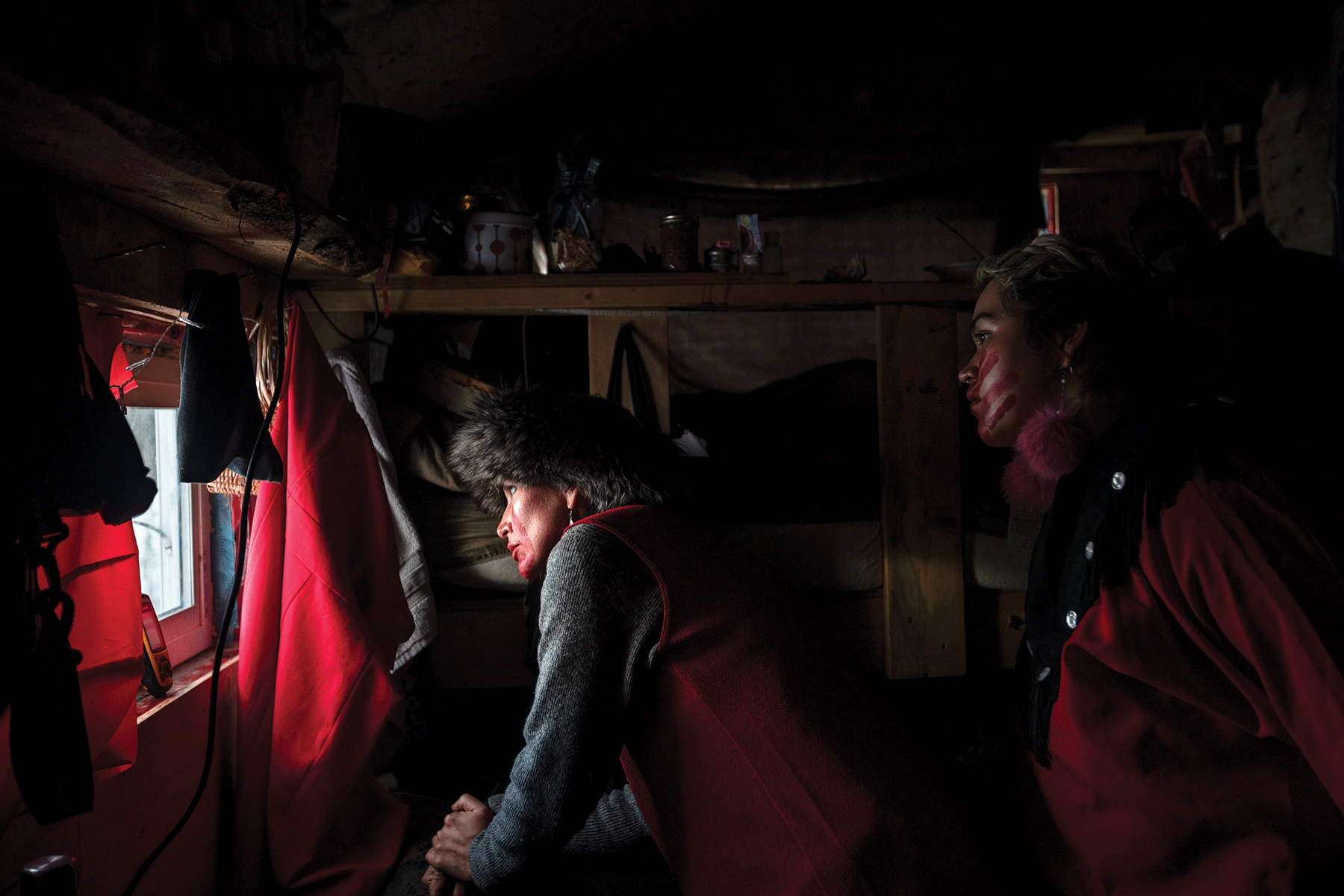

In November 2021, freelance photojournalist Amber Bracken went to Coyote Camp, or the occupation camp, to document the opposition to the pipeline construction and the latest round of conflict between the Wet’suwet’en people and the builders of TC Energy’s Coastal GasLink. In 2019, when she first reported on the opposition, the RCMP’s methods were less overt compared to their current approach. The natural gas pipeline, originating in Dawson Creek and spanning 670 kilometres, is intended to run through Wet’suwet’en land on its way to LNG Canada’s Kitimat facility for processing and export. Protesters had gathered to intervene and stop the construction. Bracken was on assignment for The Narwhal, a non-profit, environment-focused online magazine.

Carol Linnitt, The Narwhal’s executive editor and cofounder, wrote in an email that the parameters of Bracken’s reporting were discussed in advance. She was provided with a press pass and, in case the RCMP approached her, a letter of assignment to carry with her while reporting. The Narwhal also contacted the RCMP directly to inform them that Bracken would be reporting on the ground. Linnitt had contacted the RCMP once before, in 2020, when Bracken was reporting on a similar situation. “We asked that the RCMP please do everything they could to ensure that all of the units there are aware there is an accredited journalist on location,” wrote Linnitt. According to her, the RCMP senior media relations officer confirmed receipt of the email, stating that as long as Bracken identified that she was media with the officers, there shouldn’t be any issues.

Bracken had covered the opposition for three rounds of enforcement and was prepared each time, but in 2021, she was caught off guard and required to react to an escalating situation. Given the remoteness of Coyote Camp, Bracken felt it was important to document the varying accounts from both police and protestors. Bracken says police tactics had changed since the last two times she was there. In 2019, she says the police would approach from the road. In the next round, there were more camps. “It was an evolving series of enforcement,” she says. “There was kettling tactics, so they would come from the road and they would also airlift people from behind.” By the next year, Bracken says the police were not letting people in at all during enforcement.

Exclusion zones were between 20 to 60 kilometres by 2021, have made covering the opposition unrewarding and difficult. “Even a kilometre is too far,” says Bracken. “You can’t see anything.” She believes this was a huge factor that explains why established media are unwilling to cover the opposition. In her first year, various legacy media and large newspapers were there. By 2021, though, aside from APTN, it was down to smaller news media and local reporters. “Media stops covering because they can’t get access through the police lines,” she says. “And the police get normalized to the idea that media shouldn’t be there.”

Additionally, being a stranger with a camera in a conflict zone creates, almost by definition, one level of discomfort. But being a female with a camera in a conflict zone means dealing with intense, uncomfortable interactions with men, and men become part of the risk assessment. “One of the hardest things about being a woman and working in the field is navigating mostly men’s ideas of who you are and what you want from them,” she says. “Always having to have that safety alarm in the back of your mind.”

On November 19, 2021, the day of the enforcement, Bracken, documenting protesters who had locked themselves inside a tiny house, found herself staring at a giant weapon pointing directly at the little structure she was cramped inside. She didn’t know if it was a grenade launcher, tear-gas canister, or actual gun. “It was incredibly tense and very scary,” she says. She continued photographing the unfolding scene, but her body was reacting. “All of my joints were vibrating. Honestly, my whole body was quaking, and it didn’t stop until later.” When the RCMP surrounded the cabin and pointed weapons, everyone put their hands up, except for Bracken and another person who was filming. “Here I am with my camera in my hand,” she says, “and I was afraid to even switch cameras.” In her mind, she was scrambling and thinking about the exposure and getting the job done right while her body was trembling, communicating danger.

Bracken was arrested, along with protestors, as the RCMP arrived to enforce a court-ordered injunction to allow pipeline construction to continue without threat to the project. After Bracken’s arrest, Linnitt says, “The Narwhal made several requests to the RCMP that she be released from detention immediately.” They made efforts to locate her equipment, which was only returned upon her release. The Narwhal also provided Bracken with legal representation. The Narwhal, along with many other media outlets, such as The Breach and Canadaland, signed onto an open letter from the Canadian Association of Journalists to Canada’s public safety minister, calling on him to “immediately release journalists Amber Bracken and Michael Toledano, and to bring about a swift resolution respecting journalists’ fundamental rights.” The Narwhal also connected with other publications, organizations, photojournalists, and editors to lend support for her release. Bracken was released on bail a few days later.

Bracken says The Narwhal did everything it could in an inherently disempowering situation. She’s unsure of what would have happened if she were working with somebody else. “That’s the scary thing about being independent,” she says. “You hope that outlet would support you, but have no guarantee.” She says that many contracts don’t codify responsibility for reporters, so they’re on their own. She believes this situation circles back to there being few staff positions for photojournalists in Canada. “Nobody has the budget for it, nobody wants to invest in it, so there’s a tap dance around not wanting to be responsible,” says Bracken. She believes being legally responsible for things that happen to photojournalists on assignment is a lever point for unions, to say newsrooms should hire them—a game newsrooms don’t want to play because nobody can afford it.

Although she does not want to speak for other newsrooms, Linnitt says that freelancers, freelance photojournalists in particular, are doing some of the most difficult reporting in Canada, often without support from publications. “They’re routinely underpaid and unsupported while they’re out in the field and don’t enjoy the same benefits and access to editors as staff reporters.” The Narwhal does not have any photojournalists on staff and relies heavily on freelancers. Linnitt believes that “it cannot become commonplace” that the publications photojournalists freelance for, and often put themselves at risk for, not provide basic support, especially when they are being asked to enter conflict zones.

In February 2023, Bracken and The Narwhal filed a lawsuit against the RCMP. The grounds were, according to Linnitt, that “Bracken’s liberty rights and The Narwhal and Bracken’s press freedom rights were unjustifiably breached.” The Narwhal’s FAQ article regarding the case says, “This case aims to establish meaningful consequences for police when they interfere with the constitutional rights of journalists covering events in injunction zones, including both journalists’ liberty rights and the freedom of the press as protected by section 2(b) of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms.” The magazine is suing for damages for Bracken’s wrongful arrest, detention, and interference with her constitutional rights, and the trial is scheduled for this fall. “We are a small nonprofit and there is extraordinary risk in taking a case like this forward,” says Linnitt. “But ultimately, we felt we could not let what happened to Amber and to The Narwhal go unaddressed.”

Bracken, like most photojournalists in the country, has concerns about the future of photojournalism in Canada. She believes newsrooms are unlikely to invest in photojournalism as a tenet of reporting in a meaningful way, and the ongoing struggle to gain access to cover breaking news in high-risk zones will only deepen. And yet, no one is giving up. Bracken says, “It’s the people that give me hope.” Despite the shrinking state of journalism, photojournalists in Canada continue to be the eyes of the public, pushing for transparency. “We need to do some serious reevaluation,” says Bracken, “or think deeply about how we can work together to create an industry that truly represents the values of democracy and common good.”

About the author

Prarthana is a second-year Master of Journalism student at TMU. She’s an assistant reporter at the Investigative Journalism Bureau and a producer for Beyond the U podcast series at Toronto Met Radio. She additionally has work published in Maclean’s, Broadview, and other publications. She is passionate about sharing socio-political stories about displaced and vulnerable communities on a global scale.