Why it’s time to learn from student media when it comes to sexual assault coverage

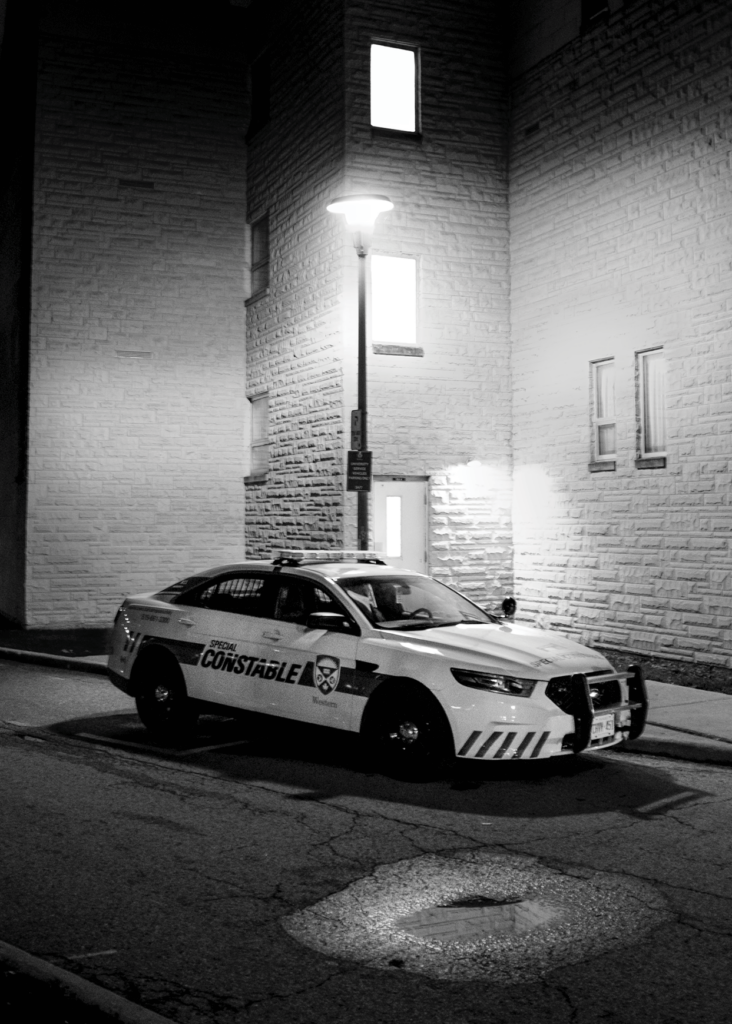

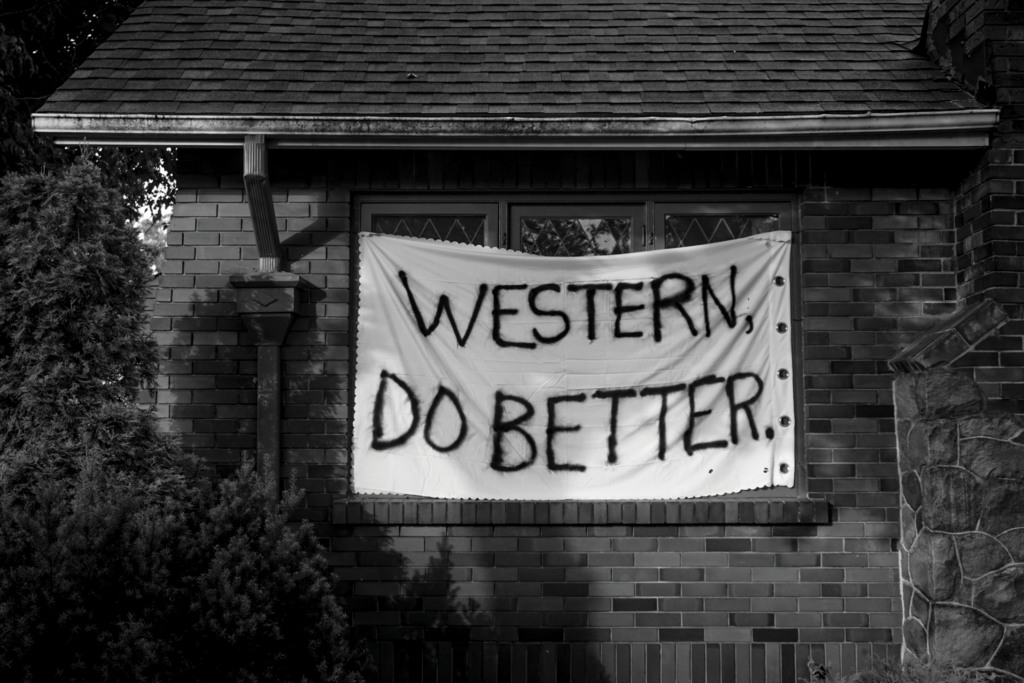

Editors’ Note: All the photographs and captions in this article first appeared on The Gazette’s website in the joint investigation by Gazette and London Free Press: “‘I Couldn’t Move’: How Western’s OWeek ended in violence and trauma.” The photographs and captions were taken and written by members of the Gazette staff.

It was Saturday, September 11, 2021, the last day of covering frosh week nonstop, and Hope Mahood was tired. The coordinating editor of The Gazette, Western University’s student paper, had been covering frosh week since the opening ceremonies on Monday, running from building to building to juice up her phone battery during events in order to capture every moment of the festivities. That night was the closing ceremony, an indication that things would soon calm down. Yet Mahood had a gut feeling that something wasn’t quite right. Even with the COVID-related myriad of social distancing fences and a booming big screen, there seemed to be fewer sophs—second-year student mentors—milling about on University College Hill than during the opening ceremonies. Entire faculties of sophs were missing from the designated cheering areas at the base of the hill. When the lights shifted to focus on cheers from the science sophs, there was silence. “You could feel a heaviness over what was supposed to be, and what always was, a happy, celebratory event,” says Mahood. Instead of the customary cheers, the sophs began to march down the hill chanting, “Western, keep our students safe.”

Taking off toward the fences that kept her separated from the sophs, Mahood asked the student leaders what was going on. Where were all the missing faculties, she asked. Repeatedly, she was told by the sophs that they couldn’t talk about what was happening, but they thanked her for looking into it. Mahood soon discovered what the demonstration was about: On September 10, the final Friday of frosh week, an unconfirmed number of people had been drugged at the university. The drugging took place at a party in a residence known as Medway-Sydenham, or Med-Syd. Several of the affected individuals were first-year students—the exact number could not be verified—and at least one student was sexually assaulted.

News of the attacks first circulated on social media over that weekend. In the comment section of a TikTok that has since been deleted, a user says “30 girls got roofied” at the London university. A tweet referencing further TikTok comments described “30 girls at Western University were drugged this weekend, and two sexually assaulted.” Another TikTok user from Western posted a video saying she was “scared to even leave [her] own building” in light of the assaults. A Twitter thread from a soph who witnessed the aftermath of the drugging described seeing “ambulances rush to three separate girls.” She added that the university had “failed to keep [students] safe.”

“Everyone [at The Gazette] wanted to tell this story, but not to sensationalize what occurred, not to have our reporting appear exploitative,” says Liam Afonso, editor-in-chief of the paper. “This is our campus. Our office is probably about a 10-minute walk from Med-Syd. Our writers had siblings there, family members. Everyone has connections to what happened,” he says. To him and his team at The Gazette, none of whom speak for the university in an official capacity, these survivors were not just students at a university two hours’ drive from Toronto; they were friends, classmates, neighbours. And that proximity informed their reporting to see beyond the assaults as isolated incidents. The Gazette first published the story less than two days after the assaults. The piece describes the allegations made online, the email sent to the residence, and the student leaders’ protest at the end of frosh week. External media sources such as the Toronto Star, The Globe and Mail, and CBC quickly followed suit with stories over the next few days. Before long, journalists from across the province began to hail down on Western’s London campus, pointing cameras and asking students about what happened in Med-Syd. But as soon as the story had made its way through the news cycle, the journalists were gone, leaving students grappling with the trauma of what had happened on the campus they called home.

How sexual assault is covered in journalism has been front of mind in recent years, as media reckon with their ability to shape public perception. The #MeToo movement, which began in 2017, brought numerous high profile sexual assaults to the front pages—from former Hollywood bigwig Harvey Weinstein to disgraced CBC Radio star Jian Ghomeshi. Along with these stories came conversations about improving sexual assault coverage to better respect survivors. Newsrooms began to reexamine everything about how they reported on sexual assault, from the manner in which they interviewed subjects to the language they used in their pieces. But when it comes to covering sexual assault, the work of campus media is often hidden—despite the prevalence of sexual violence on university campuses.

According to a Statistics Canada study, one in 10 female-identifying students reported being sexually assaulted on post-secondary campuses in 2019. While school papers are often viewed as less-legitimate sources of journalism than larger organizations—they usually have smaller and less experienced mastheads and serve fewer readers—they’re leading the way in Canadian sexual violence coverage. Their coverage is often more trauma-informed and calls into question the external factors that perpetuate sexual assault on campuses, a perspective they can credit to their microfocus understanding of the community. It’s a practice that’s not just succeeding in restoring dignity to survivors—it’s revolutionizing how Canadian media cover sexual assault. As Afonso puts it, “Campus newspapers are in a very interesting place. It’s more than local journalism, it’s almost hyper-local journalism. That allows us to really specialize in reporting [on our university]. We have that institutional knowledge.”

When The Gazette broke the Med-Syd story on September 12, the newsroom thought a lot about how to cover this story the right way. “I approached it first from a personal level, someone who was a residence soph, who did live in residence for two years, someone who remembers what it was like just a few years ago to be a first-year student,” says Afonso. The breaking-news piece The Gazette produced references an email from the school to the Med-Syd residents that referred to the drugging as “incidents of gender-based or sexual violence,” as well as including what the school was doing to increase safety. The piece, which ran without a byline, also noted how the attacks were directly impacting the students beyond September 10. Specifically, it mentions a “mass disruption” performed by sophs, a mentor-type role taken on by second-years during frosh week. The science faculty sophs chanted, “Western, protect our students,” at the week’s closing ceremony, while other soph faculties boycotted the event. Throughout the piece, the article references the lackluster responses from institutions of power within the Western community: London Police Services, Western’s president of housing, student council, and the residence life coordinator for Med-Syd. To conclude, the article listed sexual assault resources that are specific to the Western community and refrains from naming any accused perpetrators.

But not all news organizations that covered the Western story took the same student-centred approach. Afonso describes the unsettling feeling within the student body when external media sources descended to cover the assaults. “We had to do a lot of balancing between telling the story and being respectful to our community,” he says. “When you’re walking into your residence and there’s news cameras there, people did not feel safe, they did not feel welcome. That’s what we were trying to mitigate….It was a lot of parachuting.” On the same day The Gazette released its first story, the Canadian Press also published its own about the assaults at Western. The CP story was picked up by the Toronto Star, the National Post, and The Globe and Mail. The article, which has no byline, describes unspecified sexual violence prompting a university investigation and quotes Western’s president of housing saying the school doesn’t tolerate sexual violence. The piece ends by underlining that neither the university nor the London Police Services has received formal complaints. CTV London’s breaking news coverage of the assault was similar. In the broadcaster’s online piece, Western officials are quoted saying the school is “investigating” and “following up with information.” The article concludes by mentioning the police have not commented.

Dart advises reporters to “tell the whole story….abuse might be part of a long-standing social problem…or part of a community history”

The Dart Center for Journalism & Trauma, which is run out of the Columbia School of Journalism in New York, offers standards and guidelines for reporting on sexual assault. The first thing it advises when reporting on sexual violence is “research local conditions and circumstances.” Dart advises reporters to “tell the whole story….abuse might be part of a long-standing social problem…or part of a community history. Finding out how individuals and communities have coped with the trauma of sexual violence in the longer term may add helpful insight.” Sexual violence, Dart emphasizes, has “wider public policy implications.” The organization cautions writers to be mindful “when deciding how much graphic detail to include. Too much can be gratuitous.” Language is also a key component, with Dart underlining that “rape or assault is not ‘sex.’”

An understanding of local impact beyond the original incident is what is missing from the external pieces. Despite being published on the same day as The Gazette piece, the Canadian Press and CTV pieces feature no discussion on how the fellow students were feeling in response to the attacks. There is no coverage in these pieces about the sophs’ disruption in protest of the lack of campus safety, for which they felt the university was responsible. The external pieces present the attacks as an isolated, if even hypothetical, incident, framed as less noteworthy because no formal reports have been made to police or university personnel.

Although external coverage does become more detailed as more information comes to light in the following weeks, the trust and understanding The Gazette had built with the community, as well as its commitment to care, led to a more informed piece from the get-go. In The Gazette piece, readers can see fellow students were immediately affected—so much so they made a formal protest. By quoting the sophs’ chant, “Western, protect our students,” it alludes to the idea that the students view Western as at least partially responsible for sexual violence on campus. As members of the Western community themselves, reporters at the paper understood the significance of senior students like sophs refusing to fulfill their duties while calling out the school. Though The Gazette mentions the police’s statement that no formal reports had been made, by featuring the soph protest, the paper bolsters the truth behind the violent accusations, even without a formal report at the time of publication. In doing so, it tells a more locally informed and trauma-sensitive story, while also bringing the role of the institution into the light.

Sexual assault on campus is not isolated or unique to Western. More instances of assault occur than those that are picked up by mainstream media, or even campus media, for that matter. But more often than not, reporters at campus papers are aware of those assaults that don’t make the news, and that knowledge feeds into the fabric of their reporting. In November 2017, two students at St. Francis Xavier University were charged with the sexual assault of an 18-year-old female student (disclosure: I was a student at St. FX at this time and worked for The Xaverian Weekly, St. FX’s student newspaper, though I did not cover this case). The assault occurred at a student residence after a social event called the Catalina Wine Mixer at the Golden X Inn, the student bar on campus. Much like the Western frosh week cases, the assault brought a rain of journalists to the tight-knit rural Nova Scotian town. For the next two years of trial proceedings, St. Francis Xavier’s name was plastered on newspapers across the country as the court case played out and further assault stories emerged. As 2017–2018’s co-editors-in-chief of The Xaverian Weekly, Claire Keenan and Ian Kemp chose to cover the assault differently than how external media were doing it. “I remember having some really frank conversations, Ian and I, about how we wanted to go about covering it,” says Keenan. “We didn’t want to sensationalize what was happening on campus. And we also wanted to do it in a very trauma-informed, sensitive way.”

In the 2017 issues of the Xav, you will not find the perpetrators’ names, the victim’s name, or even a description of the assault. There isn’t a reading of charges, nor are there quotes from the trial. The Xav directly references the case only once, in an article by Keenan published in the December issue. She boldly calls out the university for previously choosing to “sweep reported assaults under the rug.” The Xav would never publish the names of the accused. Keenan refers to that decision as refusing to give the perpetrators “more fame and attention than they have already acquired,” saying choosing to name the individuals “is inherently wrong.” She also wrote: “Publishing names when the accused have already had charges laid against them does not increase public safety nor does it benefit the survivors in any way.” The Xav wanted to make it clear that “the story is no longer about the perpetrators.” Instead, the paper and its readership would be sure to “focus on providing better support for survivors.”

“It’s the paper’s job to inform people, but it’s the institution’s job to actually protect them.”

“I remember feeling a tremendous amount of responsibility as a woman, as a student….I understood how it impacted the campus, especially having lived on campus, [seeing] the level of fear that was there,” says Keenan. In March of that school year, Keenan and Kemp, neither of whom speak for the university in an official capacity, went a step further and published a sexual violence issue of the Xav. Inside were direct calls to the university’s administration for change, specifically within the school’s sexual violence policy and the on-campus access those accused had during the investigation process. The issue also featured multiple anonymous contributions from those who had been assaulted during their time at St. FX. “I wanted to make sure that all the shortcomings of the university and room for improvement was very heavily covered,” says Kemp. “It’s the paper’s job to inform people, but it’s the institution’s job to actually protect them.” “We wanted [the sexual violence issue] to be an issue that people felt comfortable writing in and having it as a holding space for them to speak about their experiences with the school or how [St. FX] failed them. We wanted it to be clear that it was something we supported,” says Keenan in regard to publishing anonymous pieces.

In many ways, the Xav’s decision to not detail the assault or cover it in a traditional sense broke a lot of journalism rules. Anonymous sources and contributors are usually not preferred in mainstream publications. Intentionally choosing to not publish most details of a high-profile event in your community is also not common. But what the Xav did here was actually more in line with trauma-informed reporting than traditional coverage. Farrah Khan, longtime feminist advocate and co-creator of “Use the Right Words,” a guide for Canadian media reporting on sexual violence at femifesto, a feminist organization that works toward building consent culture, cautions journalists against “giving unnecessary information about” the accused or “framing them” in a way that detracts from their role in the assault. Journalists need to unpack their “own internalized myths about sexualized violence” and “the biases that they may hold” that may present themselves in discussions of the survivor’s dress, lifestyle, and/or alcohol consumption. Echoing the Dart guidelines, Khan asks journalists an important question that they should consider in their coverage: “[Do] you need to include such detail about [the assault]? And if you [do], why?” Khan also emphasizes the importance of local understanding by telling reporters to build relationships in the community prior to a source being required for a story, in order to avoid parachuting. “If you’re going to go in [to a community], learn about the issue before you go in” to be able to properly analyze the environment. “What’s missing oftentimes is the systemic piece,” says Khan. “We need to talk about policy. It’s a policy fail that sexual assault continues.”

In keeping with Khan and Dart’s guidelines, the Xav is correctly focusing on the long-standing social problem and community history when it comes to assault. It was no secret to Keenan and Kemp, who were also students at St. FX, that sexual violence was a pervasive issue on campus. “We approached everything we did with a big-picture type of lens. For a lot of these students, the Xav would have been their only voice. CBC or CTV wasn’t going to interview them for an hour and get every little detail. Being the voice for the people who not necessarily would have one, we approached it from that lens,” says Kemp.

Much like with the Western case, not all media chose to take the same approach to covering the St. FX assault that the campus paper did. SaltWire, an East Coast online publication, covered the case from the arrest through to the end of the trial.

Not only did its coverage name both of the accused in the case, but in an article titled “Accused in St. FX Sex Assault Trial Says He Got Consent from Woman,” the writer, Aaron Beswick who covered the entirety of the trial, quotes one of the two accused’s cross-examination. The article is told from the viewpoint of one of the assaulters, with a single sentence stating that the survivor said she “never provided consent” and “resisted physically.” In another article, Beswick included information about the 18-year-old survivor’s menstruation and specific graphic aspects of the assault. Some readers were dismayed by this coverage—so much so that SaltWire published an opinion piece by a reader on October 29, 2019, that said Beswick’s style of coverage “is one of the reasons many sexual assault victims don’t report it.” The writer specifically took issue with Beswick’s inclusion of “explicit details” by stating “where private parts were put, touched, and tampon use…is nobody’s business besides the people involved.” In response, SaltWire published a letter from Beswick saying he chose to include these details in an effort to “shine a light on the ordeal women go through in our courts.”

Campus publications are revolutionizing sexual violence coverage in a way that respects survivors and holds the powers that be accountable

Seventy-one percent of Canadian post-secondary students “witnessed or experienced unwanted sexualized behaviours in a post-secondary setting in 2019,” according to a Statistics Canada study from that year. As such, our media can and should be reporting on the prevalence of sexual assault on campuses. But there is a better way to cover something that is both intensely personal and deeply tied to public policy. Campus publications are revolutionizing sexual violence coverage in a way that respects survivors and holds the powers that be accountable. Their understanding and trust in the community, two pillars of trauma-informed reporting, simply cannot be replicated beyond the campus borders. But that doesn’t mean external media doesn’t have a place in covering campus sexual assault. The Gazette quickly recognized that the Med-Syd story was going to be big—and that it could benefit from the experience of an external news organization. Afonso reached out to The London Free Press for assistance. “It was a natural progression…it made sense to pool our resources. We had the sources and the connection, and the understanding of Western, and they had the experience,” he says.

Shortly after connecting with Afonso, Randy Richmond of the Free Press arrived at The Gazette. With the blinds pulled down in Afonso’s fishbowl office, Richmond, Mahood, Afonso, and Gazette reporter Lucas Arender got to work. “[The Gazette] came with the story…if we’d done it by ourselves, it would’ve been far less impactful and far more difficult to get. They had students’ trust,” says Richmond of the partnership. “My role became trying to help them: offering tips on how to get more information, how to firm up some sources…but largely to help them structure the story…and how not to be overwhelmed by it…it was largely their story, and we helped.”

The result was a groundbreaking piece that ran simultaneously under both mastheads: titled “‘I Couldn’t Move’: How Western’s OWeek Ended in Violence and Trauma” at The Gazette and “Western University’s Dangerous OWeek: An LFP-Western Gazette Investigation” at the Free Press. The story, which is nearly verbatim in both editions except for the title, splits a byline between Arender and Richmond. In this piece, anonymous survivors from the Med-Syd assaults share what happened to them that evening, while explaining how they felt the school failed to protect the students from “rape culture,” as well as failed to equip student leaders with proper crisis training and support. This partnership created an environment where students at Western were able to share their experience from that night with people they trusted, while also reaching a larger audience that had the capability to put pressure on institutions like universities. “It can be difficult for a news organization to automatically trust student journalists because they’re students. But I was impressed right from the start: their ability to realize they needed to take a big picture [approach], they were cautious, rightly so, their desire to be complete and, of course, their sensitivity. And they of course had to trust us,” says Richmond. “We both had what the other needed…our collaboration allowed us to [tell the story] right,” says Afonso.

Richmond notes that since the publication of this piece, his newsroom has added The Gazette to their morning news checks. “It’s a great idea,” he says of inter-newsroom partnerships with campus publications. “I don’t know if we really recognized [until working together] how excellent they are. We’re trying to think of ways we can work with them more closely…in the future, on a case-by-case basis.”

Sexual violence is happening on every campus across Canada, and journalists have a duty to report it, but they need to do it in a way that doesn’t cause further harm. Campus newspapers have demonstrated their ability to produce trauma-informed coverage that steers clear of salacious, useless details in favour of highlighting the local impact of sexual violence and policies that perpetuate this heinous crime. Campus journalists have the local expertise and the trust, while external publications have the experience and reach to access a large audience that such important stories deserve. When we remove outdated power dynamics through partnership, journalists can cover sexual assault in a way that neither type of newsroom can do alone.