Queer media began small but unified. Now they’re more prolific, but some 2SLGBTQIA+ journalists say this risks losing the strength of a collective voice

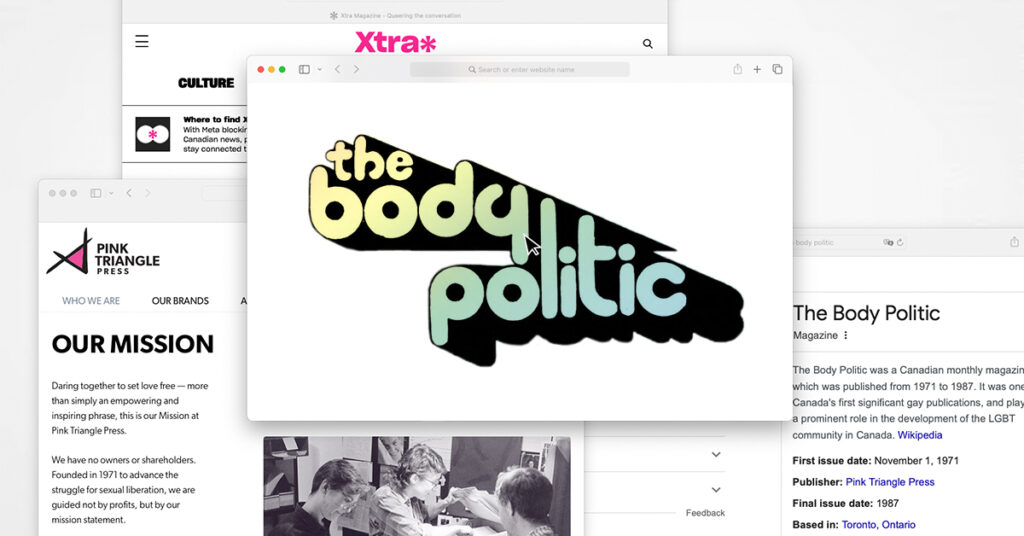

There was a time when queer lives and stories were rarely in the media. In the last four decades, though, there has been a slow but steady increase in 2SLGBTQIA+ voices in journalism. In Toronto, this has been made possible because of the groundwork laid by the Body Politic, a collective of gay and lesbian writers and journalists that, between 1971 and 1987, produced a monthly magazine with an eye for amplifying discussions of gay liberation and the fight for gay rights. “We gave heart at the time and courage to the people. That was important, but was within a small, small world,” says Ed Jackson, writer, journalist, and decade-long member of the Body Politic editorial collective.

Since then, the landscape of queer media has undergone considerable shifts, especially after entering the digital age. The internet has ushered progress: “The social media aspect—that’s where a lot of my LGBTQ news comes from,” says Sarah Krichel, The Tyee’s social media manager. “That’s where I keep tabs on the community and where people are at.” But online platforms have also produced new challenges. With the current state of the journalism industry where freelancing is becoming the norm, the 2SLGBTQIA+ community is losing its strength as a united force.

Krichel wrote a 2019 online story for the Review of Journalism about the state of Daily Xtra, which was then shifting to serve a more global audience. In the piece, Lauren Strapagiel, a freelance queer journalist, highlighted the importance of small publications that focus on local communities. “We’ve seen some really major publications go, but it’s the small, independent LGBT-focused publications that got hurt the quickest and the hardest,” Strapagiel says. “It’s disappointing because where are you supposed to look for LGBT hyperlocal coverage now?”

Social media can still allow for different connections and community building. However, with the breakdown of hyperlocal queer publications, the community also loses its political voice and the aggregating apparatus that might inform its decisions as to which stories to tell. Krichel shares Strapagiel’s concern, saying, “I want to continue to see political news around what is happening to 2SLGBTQIA+ communities across the world.”

The democratization of online content creation has led to a fragmentation of narratives, giving space to a larger number of voices in detriment of a more unified single voice.“If you have a podcast or Substack, or whatever it is you’re writing in,” Jackson says, “it becomes more personalized, and maybe less collectivized in some ways. People were really isolated in those early years. Now people are individualized, but not isolated in the same way, so I wonder how that’s affecting what people are reading about.”

Ken Popert, Jackson’s former coworker at the Body Politic and executive director of Pink Triangle Press from 1974 to 2017, echoes this sentiment. “It’s a good thing and a bad thing. The aggregating apparatus made it possible for some stories to get to the public.” At the same time, Popert continues, it filtered out other stories that weren’t supported by the money from advertisers.

Popert believes that one way for a political movement to succeed is by getting support from the masses. “That’s what I fear has been forgotten because of this emphasis on individual stories and struggles.”

He says it’s important for young journalists to understand why they want to be in this profession. “You have to know what it is you want to accomplish by bringing things to people’s attention. It’s never going to be just reporting, observing, and writing down what you saw. Maybe it never was—we just fooled ourselves.”

Popert ends bleakly, saying, “A sense of wanting to change the world and speaking to other people and persuading them—that’s what’s missing, the will to engage people who don’t agree. That’s sad. It’s gone.”

About the author

Mariana Schuetze is a fourth-year undergraduate journalism student at Toronto Metropolitan University. She is the Editor-in-Chief of CanCulture Magazine and works at TMU’s radio station, Met Radio as the Collective Coordinator – so she spends most of her time looking over other people’s work and replying to emails. In her work, she loves to talk about arts, culture and their importance to society.