How protest news frames Indigenous movements across Canada

Three of my sisters and two of my nieces are in the Pines the morning of the shooting. My younger sister, Kasennenhawi, Gussy for short, hears bullets snap by her, sees sand kick up around the other women and children as they dive for cover, feels the splinter of bark as bullets gouge the trees they hide behind. Later, she wonders why no one else was killed.

She’s afraid at first, standing there with the other women only yards from the police—but not of dying. There’s something else in the Pines that morning. To this day she can’t describe it. The police aim at the women with tear gas and concussion grenades. These explode all around them. The women should be wounded but they aren’t. A sudden wind springs up, blowing tear gas—meant to render the women weeping and powerless—back toward the police. The women feel a strange calm settle over them. They know someone or something is watching over them. But Gussy can see only death in the eyes of the police. She knows someone will die that day.

— Dan David, “All My Relations,” This Magazine, 1997

Years before Tahieròn:iohte Dan David, a member of the Kanyen’kehà:ka (Mohawk) community became a journalist covering the Oka Crisis, he was a jack-of-all-trades: from delivering the Montreal Gazette to picking fruit and cleaning pools as a youth; from studying photography to clearing brush along power lines; from teaching printing to working at Indian and Northern Affairs Canada until a colleague advised him to leave before his brain “turned to mush.” David worked long days as a construction worker, ditchdigger, on a garbage truck, and as a housepainter. After leaving his “nice cushy job,” he began working at a college up north, where he then took up journalism. “I think I always wanted to be a journalist,” he says. After graduating from Western University’s one-year Program in Journalism for Native Peoples, he landed his first gig in 1981 for CBC Radio.

While working as a civil servant for Indian Affairs, he remembers there being mass demonstrations across the country. During the 1980s, David attended many of these protests, and for a while, he thought somebody had put a tracker on him and there was going to be some kind of demonstration or blockade happening wherever he went. A momentous movement to him was a 78-day standoff. “The Oka Crisis wasn’t my first one, but that was probably the biggest,” he says. “It went on for three months, and it was here in my home community, and I could see how things played out.”

The Kanesatake Resistance, also known as the Oka Crisis or the Mohawk Resistance at Kanesatake, was a standoff between pro-Kanyen’kehà:ka protesters on one side and Quebec police, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police and the Canadian Army on the other. Recalling the clash that lasted from July 11 to September 26, 1990, David says, “The media was so focused on people with masks, people with camouflage, the so-called warriors, the instigators, the demonstrators, the revolutionaries, whatever you want to call them, and not looking at people who were behind. So, they didn’t get that kind of community context. They were so focused on the confrontation that they didn’t really bother to look at the roots of that confrontation.”

“Any reporter that’s hired anywhere in Canada should do that work to say, whose treaty land am I on? What are the First Nations around me?”

The Oka Crisis was extensively covered across Canada. As an act of solidarity, organized protests and blockades were held nationwide. However, the media tended to focus on those who opposed the movement, such as the Quebec residents who were angered by the blockades, especially those living in the immediate areas. Then prime minister Brian Mulroney, in a national press conference, denounced the Mohawk as a “band of terrorists,” while the Canadian Police Association published ads in major Canadian newspapers and magazines with the message “We Oppose Terrorism.”

David says journalists have a tendency to not look into systemic reasons behind protests. “The way that I tend to explain it to a lot of people is journalists like to go to do the body count at the explosion, but they don’t like to follow where it came from, who lit the fuse in the first place.”

Even though the Mohawk were not legally recognized as landowners, they had lived on the land for centuries. With the help of non-native settlers, they planted 70,000 to 80,000 pine trees in the mountain area around Oka. Over time, the Pines became a burial ground. When the town of Oka decided to annex the Pines to expand an existing golf course layout to 18 holes without Native consent, tensions arose. In March 1990, the Mohawk erected a blockade to stop bulldozers scheduled to tear up burial grounds. The municipality took its case to court and was granted an injunction ordering the dismantling of the barricade. Instead of giving up, the Mohawk strengthened their barricades and started to patrol the Pines.

Checkpoints, extensive weapons, and intimidation were tactics used by the police and military—practices David feels the media were “almost complicit” in by not opposing. “I remember clearly here when the shooting started,” he says, recalling a press conference where police chiefs were questioned about their use of force in Oka. “Police chiefs said they weren’t using any live ammunition. The people who were in the Pines that day saw the gouges out of the trees and the bullet holes through the lacrosse box—tell them there wasn’t live ammunition being fired at them. But the reporters heard people in authority say that, and that was the end of the story.”

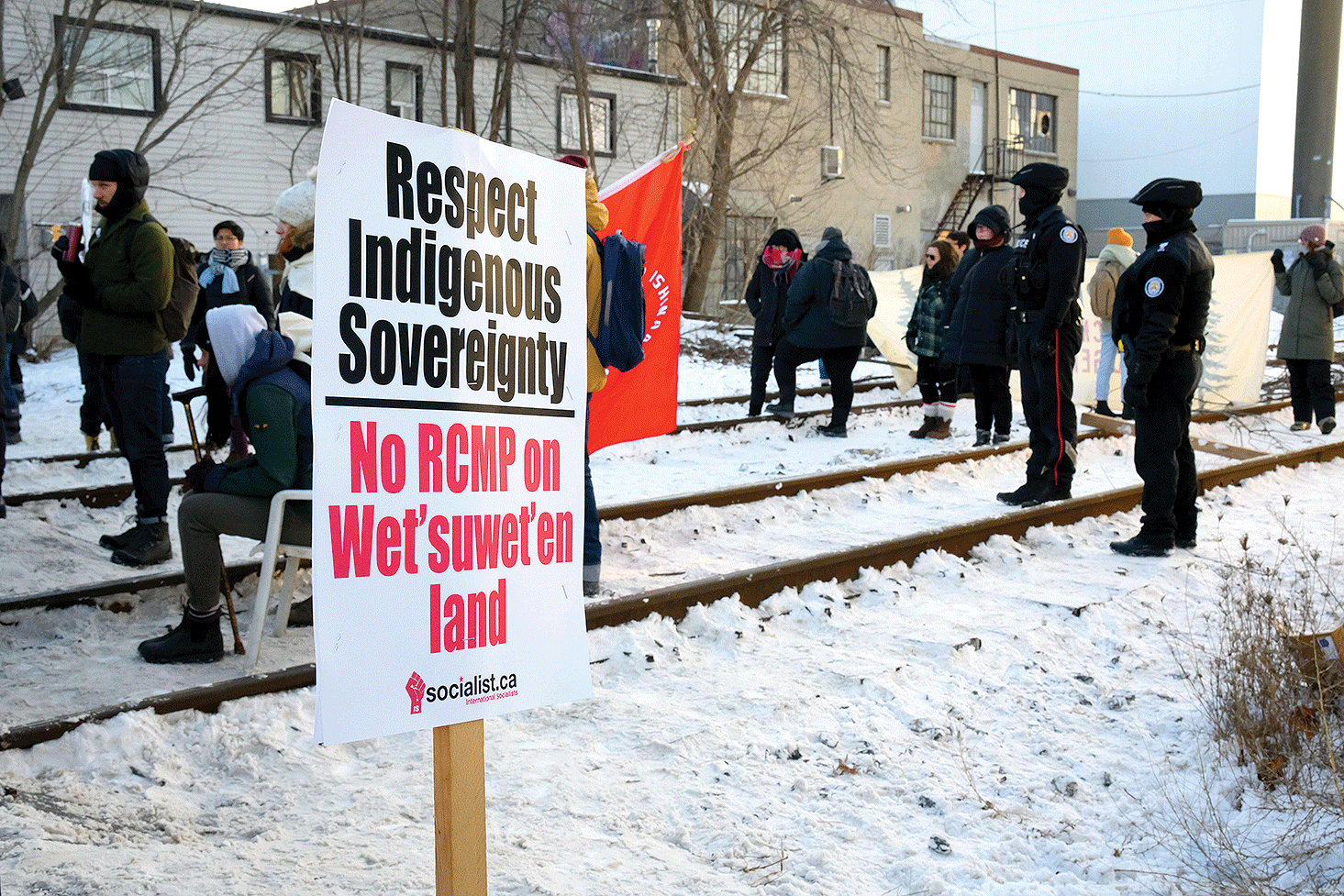

Decades later, misrepresentations of Indigenous people, communities, and their affairs persist in Canadian news coverage to this day. In 2009, the Wet’suwet’en established the Unist’ot’en healing village, which began as a Wet’suwet’en-operated checkpoint on the road, preventing people working on the pipeline from accessing the territory. On February 6, 2020, the RCMP raided Unist’ot’en, arresting six people. The Intercept reported that in response, “protesters across the country shut down ports, roads, and railways from Vancouver to Saskatchewan. A blockade set up by Indigenous-led protesters from the Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory in Ontario halted commuter rail traffic between Montreal and Toronto.”

Karyn Pugliese, editor in chief of Canadaland and director of news and current affairs for APTN from 2012 to 2019, criticizes the media’s inability to frame disputes over land properly. Protestors’ actions are distorted, as if Indigenous peoples are on the outside, “asking Canada for something that Canada should have the right to grant or not grant,” she says. “Whatever Canada does, in terms of giving them something they should be grateful for, when in fact, they are the rights holders. The power situation, in reality, is reversed.” These false frameworks misrepresent the past and the truth because people are given a skewed idea of what is happening during these movements.

Even as recent support for Indigenous movements highlights a growing solidarity with Indigenous communities, Indigenous misrepresentation in the media remains embedded in Canadian culture and continues to shape misconceptions of Indigenous identity. Reporting on Indigenous events in the media reflects our society’s view and treatment of Indigenous peoples. To dispel false and inaccurate stereotypes and long-held biased and racist perceptions their colleagues or the public may have, journalists must build and maintain relationships with Indigenous people and amplify their voices. Some are promoting a solutions-based approach when covering Indigenous affairs to avoid falling into the recurring traps and pitfalls of coverage. For example, to start, David wants newsrooms to understand that “there are really good stories out there, that you don’t have to wait for a confrontation.” And while David contends there has been some improvement, it has been painfully slow. “Things are changing,” he says. “I like to tell people change comes along like molasses in January—it just takes a long, long time.”

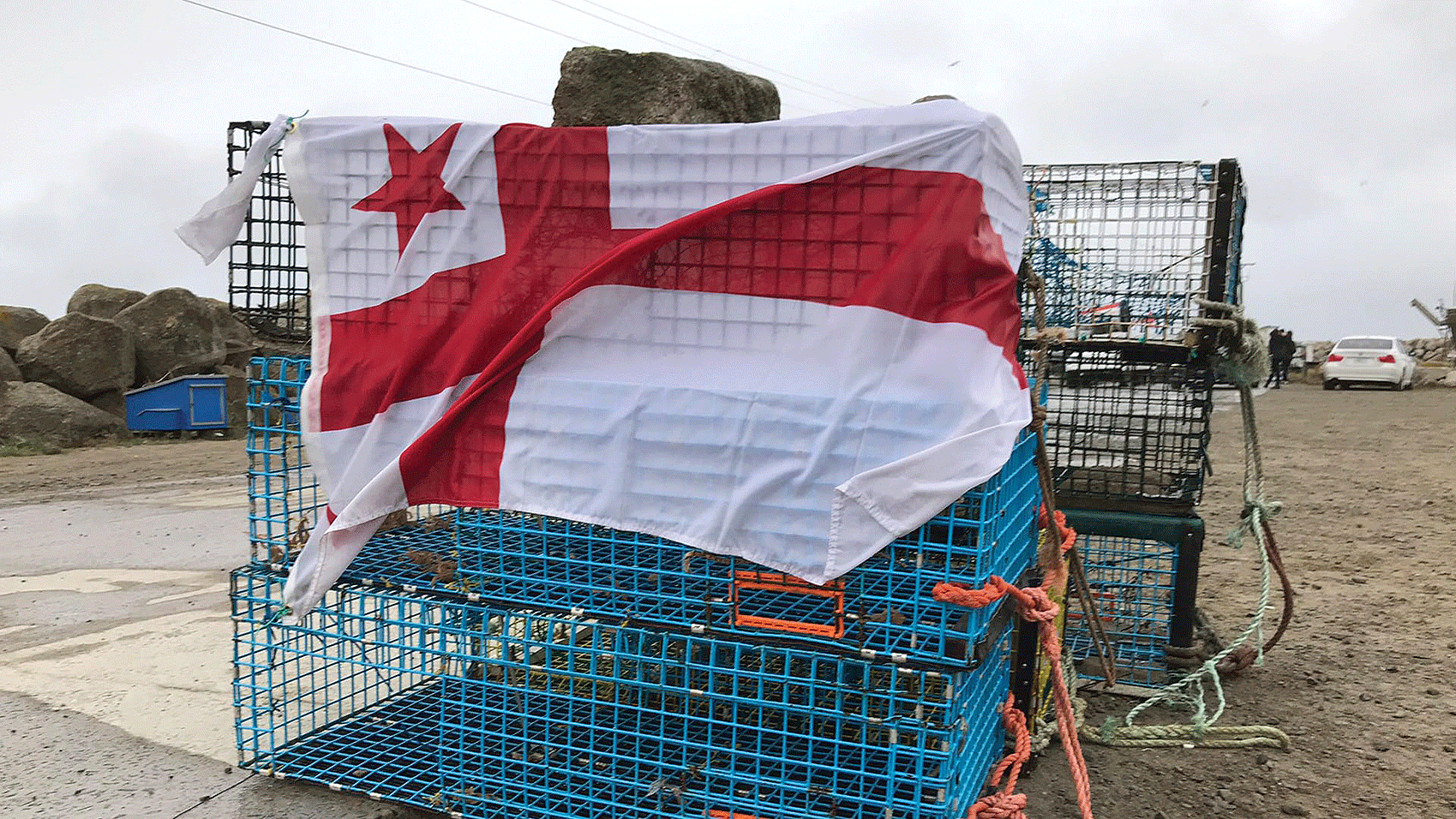

The Marshall decision, issued on September 17, 1999, was groundbreaking for Indigenous treaty rights. The Supreme Court of Canada settled a conflict between Donald Marshall Jr., a member of the Mi’kmaq First Nation, and settlers. The court affirmed the Mi’kmaq nation’s right to fish commercially in Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, and parts of Quebec to attain a “moderate livelihood.” Journalist Trina Roache, a member of the Glooscap First Nation, has been covering the implications of the 1999 ruling for nearly a quarter-century. She characterizes the media coverage of the East Coast fishery disputes this way: “There’s been really good reporting, and really bad reporting. I’ve seen both.”

It was 2001, the start of her career with APTN. With the 1999 ruling of the Marshall decision in effect, Burnt Church, the four-year conflict between the federal Department of Fisheries and Oceans and First Nations peoples from the Burnt Church reserve in New Brunswick, was filled with tension between Indigenous and non-Indigenous fishermen. A video journalist, she spent most of her summer in Miramichi Bay, covering the events as they unfolded. “It was an eye-opening experience as a new journalist.” Roache had worked for CBC Radio the year prior and had been shown the necessary tools to operate a camera while at APTN. During her time capturing the conflict, it was common knowledge that non-Indigenous objectors to the Marshall decision were destroying hundreds of Indigenous traps, fishing equipment, and fish plants. The Mi’kmaq people did not initiate any violence while continuing to exercise their right to fish. They did this as a form of protest to achieve their goal of year-round fishing for food as well as social and ceremonial purposes.

While watching other media outlets working on the same stories as her team, Roache says most of their framings did not reflect what she experienced and felt. “I was inside the barrier, standing around with warriors and thinking there is no safer place to be,” she says. “Then sometimes seeing those images in other stories, where they looked so angry and dangerous, and that wasn’t my experience.”

Fast forward about two decades, and issues of unbalanced reporting continue. Just last summer, Nova Scotia’s South Shore saw tensions rise between Mi’kmaq and non-Indigenous fishermen, leading to various confrontations, rowdy protests, and violence at two lobster pounds, which resulted in one being razed by a deliberately set fire.

This is just the latest example of a pattern that has persisted for years. On September 20, 2020, CTV News Atlantic published an article titled “‘We’ll Keep Putting Them Back’: N.S. Indigenous Fishermen Not Backing Down After Traps Removed.” The story captured the clashing perspectives regarding the commercial fishermen who removed hundreds of lobster traps set by Indigenous fishermen. Reporter Natasha Pace spoke with both Michael Sack, Sipekne’katik First Nation chief, and Colin Sproul, president of the Bay of Fundy Inshore Fishermen’s Association.

“Put the Indigenous voices first because if they’re gathering, if they’re protesting, then it’s something that matters to them, and their voices should be heard”

Duncan McCue, an award-winning CBC broadcaster and Carleton University associate professor of journalism, says this type of reporting creates “an us-versus-them relationship.” He says the comment, “This is about greed and corruption and no respect for the nursery grounds,” made by Sproul, directed at the Sipekne’katik First Nation, creates a story fixated more on painting the Mi’kmaq as the “problem” instead of asserting their treaty rights. Words in Sproul’s quote that label the Mi’kmaq “corrupt” and “greedy” can reinforce the trope that Indigenous people are standing in the way of Canada’s progress as a country, and in this instance, as an economy.

The coverage, as seen across a large sum of news outlets, created a narrative that the Mi’kmaq were in the wrong. Roache says words like “illegal,” “unauthorized,” and “out of season” have been used to describe the Mi’kmaq position, which dismisses the more significant issues of Indigenous history and treaty relations. “When we use words like ‘dispute’ and ‘conflict,’ we create this sense of two sides just butting heads. And that’s a misrepresentation of what was happening,” Roache says. “Language is a key component when reporting,” she continues. “If you don’t know what you’re talking about, it’s going to reflect in your work.”

Solutions-based journalism investigates and explains how people try to solve widely shared problems. This form of journalism can offer ways to improve Indigenous representation in the media and uncover resolutions that can break the repeated patterns in legacy media. When it comes to a solution, though, diversity alone is not enough to shift legacy newsrooms to think differently about the way they cover communities. To avoid falling into the trap of misrepresenting Indigenous people, McCue says that the first step journalists can follow is to understand the historical news discourse on Indigenous issues. “One of the really important things that journalists need to be aware of is those kinds of tropes from the past,” he says. “Whether it’s being dressed in camouflage or whether it’s wearing traditional regalia, some journalists get caught up in the shorthand stereotypes that are associated with those images.”

One possible solution for journalists is to start practising solutions-based journalism, which has the potential to halt the perpetuation of misleading beliefs regarding Indigenous affairs. To reverse centuries-old prejudices, journalists need to take the time and space to report on truth and facts. “There needs to be a definitive language to use when they’re saying Indigenous people are asserting their rights, which is probably a better way of wording it than protesting,” says Pugliese. “We need to get away from that language.”

Anishinaabe journalist Rhiannon Johnson, from Hiawatha First Nation, likewise emphasizes the impact of a lack of Indigenous perspectives in the media. “When things are being covered by non-Indigenous journalists, one of the biggest issues I see is that they lack community voices. Which is, I think, a disservice to journalism and to Indigenous communities.” She hopes this can change by ensuring community voices are present and leading. “Put the Indigenous voices first,” she says, “because if they’re gathering, if they’re protesting, then it’s something that matters to them, and their voices should be heard.”

To better report on Indigenous issues, journalists need to see the deeper context behind the disputed issues

Being conscious of the language used to report and having day-to-day conversations also humanize and show respect for Indigenous communities. This ranges from identifying Indigenous people to being accurate about who they are and making sure that they are asked where they are from. “That’s just something that shows respect,” Johnson says. “Because who we are is so linked to where we’re from as Indigenous people and our connections to our land and our history.”

Similarly, Roache considers using language in journalism a vital component of capturing the relationship between Indigenous people and the land. “When we aren’t using accurate words that really reflect what’s happening, that can be really problematic in terms of the framing of the narrative,” she says. “For Indigenous peoples to call it stolen land is just accurate. To call something a genocide is accurate. To use those kinds of words is accurate.”

Journalists should be responsible for educating themselves on Indigenous affairs before reporting on them. They can also use the four Rs as a guide to familiarize themselves with the Indigenous nations and communities of a particular space, “Reciprocity, respect, responsibility, and relationships, not reconciliation,” says Roache. “We’re not there yet.”

Further, Roache says journalists need to build trust and develop relationships with the Indigenous communities they are representing through their work. This way, when issues arise, they know who to talk to and can make sense of the events unfolding around them in a better way. “It is about building those relationships,” she says, “having respect for people, for cultures, for perspectives. Being empathetic, being able to understand, but really being able to build those relationships in advance, build trust.”

It all starts with changing the systems. In one of its 94 calls to action in 2015, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission specifically called on Canadian journalism programs and media schools to “require education for all students on the history of Aboriginal peoples, including the history and legacy of residential schools, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Treaties and Aboriginal rights, Indigenous law, and Aboriginal–Crown relations.” Roache says everyone in Canadian media should do this work to educate themselves. “Any reporter that’s hired anywhere in Canada should do that work to say, whose treaty land am I on? What are the First Nations around me? Who are the key players? What’s the history here?”

Canadian media outlets need to change the ways they are reporting on Indigenous people and communities. Since the beginning of news media, the inconsistent coverage of Indigenous issues has either intentionally or unintentionally manipulated the way that Canadians perceive themselves and the way they see Indigenous people, demonstrating just how deeply these stereotypes run through Canadian culture.

There are many articles published yearly on Indigenous affairs, yet significant gaps and distortions remain. Canadian journalists can better report on Indigenous issues by understanding the deeper context behind the disputed issues, using distinctive language in their coverage, and avoiding stereotypes and other biases. “These stories are just as legitimate, just as valuable to tell, as any other stories,” says Tahieròn:iohte Dan David. “They should be given, if not equal weight, then at least equal consideration.”

While some progress has been made, Canadian media have yet to consistently practise fair and adequate representation of Indigenous peoples in their framing of Indigenous movements. Journalists should start correcting the media narrative and addressing Indigenous issues more seriously. Journalists must embrace their roles to educate, shape, and promote public understanding while becoming agents of change within the newsroom. “Keep trying to improve,” says David. “Don’t be part of the herd. Be an outlier.”

About the author

Mackenzie MacDonald

Mackenzie is a second-year Master of Journalism student at Toronto Metropolitan University. Passionate about solidarity journalism, her research interests include social justice and human rights issues, with a focus on gathering information and statistics, surrounding matters like gender equality, Indigenous rights, criminal justice and more.