Indie mags take a page from Toronto’s zinesters

On a rain-soaked mid-December 2024 evening, Houndstooth, on the southern border of Toronto’s Little Italy, trades its gloomy red glow for warm house lights. Zine Devils is the self-made print market taking up the cafe and bar’s front stoop for the weekend. Each micro-publication costs $2 to $10, fees that barely compensate for hours of single-person editing, writing, illustrating, and distributing.

Because of dwindling advertisers, multiple Toronto publications, such as Now Magazine (Now Toronto) and The Grid, have folded their print operations in the last decade. As magazines struggle to remain viable, publishers of independent, print-first media—ranging from individually photocopied to masthead-produced—aren’t in it for the big payout. They innovate where they can, and zines offer the chance to do just that.

Writing for The Grind, a free Toronto newsprint magazine, cartoonist Jonathan Rotsztain lamented the death of Broken Pencil, the once go-to magazine for commentary on Toronto’s arts subcultures. Standing behind his table at the market, Rotsztain is selling his own photocopied-and-stapled zine, which features the column, plus bonus content.

Really Broken Pencil includes the op-ed, and a timeline of rejections the pitch sailed past before landing at The Grind. The covers are adorned with illustrator Rotem Anna Diamant’s political cartoons, the caricatures adorned with cross-hatches and sprawling squiggles. Rotsztain donates $5 of each sale to a Palestinian family’s survival GoFundMe.

For an indie magazine to survive, David Gray-Donald, publisher and editorial director of The Grind, knows editors must take the reins of their output, producing bold niche media with no guarantee of profitability. The magazine, found across Toronto locations and funded by donors and sponsored content, adds the colours of its fluorescent yellow-and-pink logo to TTC stations, independent bookstores, and political rallies. Alongside its city coverage, labour unions, social justice groups, and small businesses fill the ad space. Unlike the analytics of digital media, Gray-Donald and his employees get to see the impact of their work by watching their readers stop at city newsstands.

On the back cover of Rotsztain’s zine, a Diamant illustration reads, “Please continue to make your weird art, share your stories, and speak truth to power.” Taking a page from zinesters, as Broken Pencil once did, continues to be the way forward for indie magazines. “If people like the print publications they read,” Gray-Donald says, “support them, because it’s not guaranteed that those stick around.”

sidebar:

What’s a Zine?

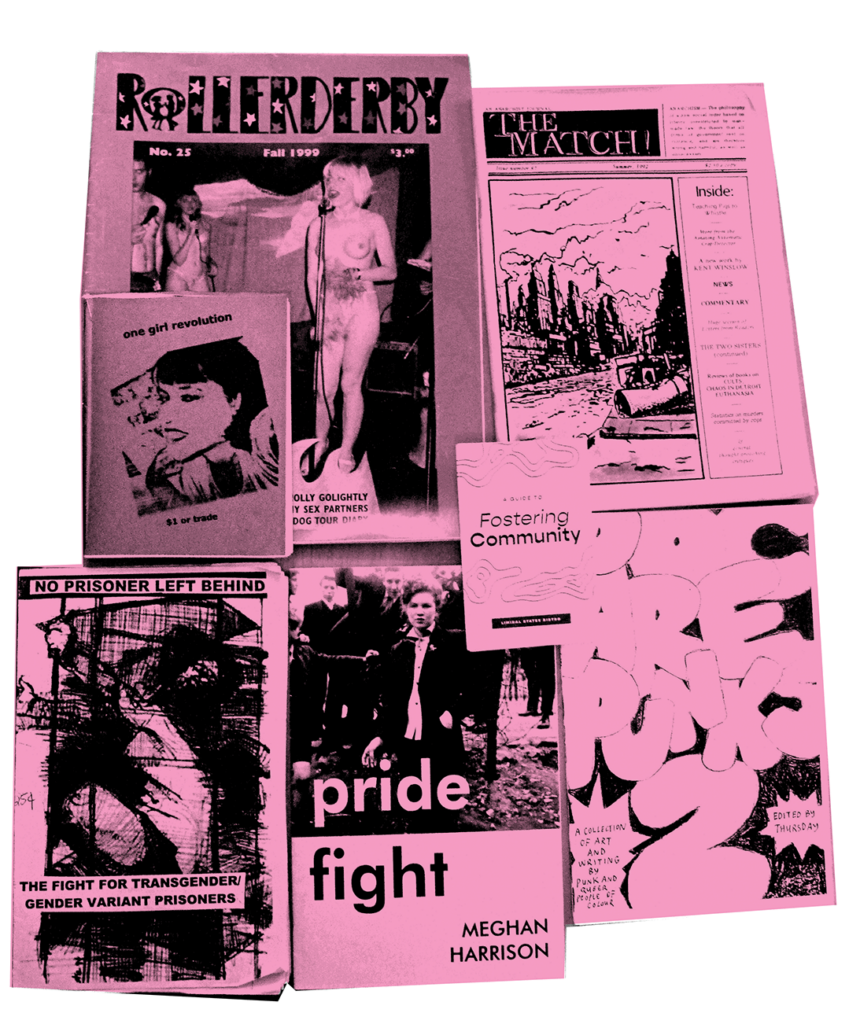

Zines are notoriously difficult to define, since the first rule of zine creation is that there are no rules. Yet they share a few common threads, being self-created and published magazines.

• Some are journalistic, consisting of articles, columns, photojournalism, and interviews, while others focus on self-expression through creative writing and art.

• Zines date back to the 1930s, reaching peak popularity between the 1970s–1990s, when they were adopted by punk music and counterculture scenes.

• Zine creation and culture was created as a means of organic knowledge-sharing, often filling the gap for marginalized communities where traditional news coverage fell short. “Zines provide a space for voices that may not be heard as often,” says Sylvia Nowak, a Toronto Zine Library (TZL) volunteer of over seven years. “These voices then find a way to form community with each other.”

• Since its establishment in 2006, the volunteer-run TZL is just one of many DIY zine libraries across Canada, and home to every genre of zine imaginable. Its primary goal is to “cherish, protect, and promote” zines and their culture.