How the Toronto Star’s I-team and The Narwhal broke the Greenbelt scandal

On November 4, 2022, The Narwhal’s Toronto office received word that a huge story was about to break. Journalist Emma McIntosh was scanning social media for any further leads. Her source divulged news of an impending—and explosive—announcement on the Greenbelt. McIntosh recalls that the Toronto Sun published the first article, reporting that Doug Ford planned to subtract approximately 7,400 acres from the province’s Greenbelt to allow for future housing development. The Ontario premier also promised to add 9,400 acres to the Greenbelt elsewhere. If the latter concession was designed to mollify the public, it didn’t work. Many were furious.

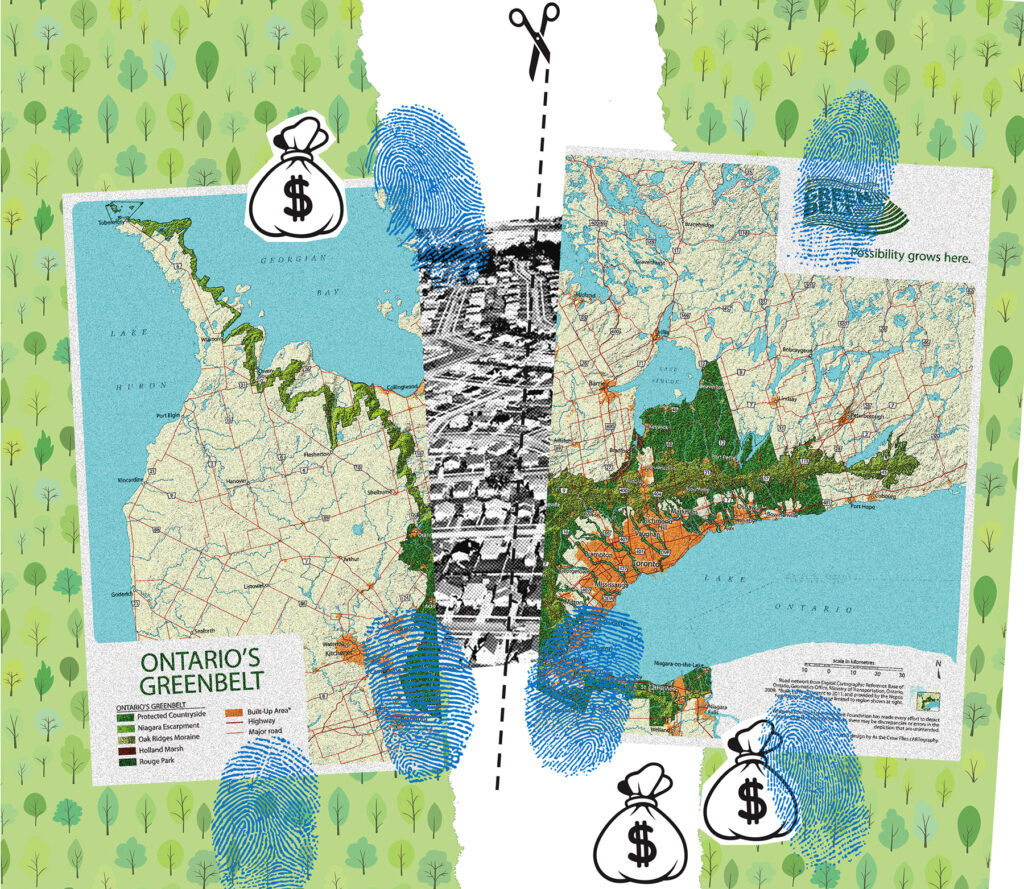

McIntosh was stunned, too. Former premier Dalton McGuinty’s government established the Greenbelt in 2005, a swath of protected land spanning roughly two million acres across southern Ontario. It contained rolling hills, rich arable earth, and sprawling forests home to sensitive ecosystems, rivers, and lakes. In 2018, Ford promised he wouldn’t touch any of it after a leaked video showed him saying he would open the Greenbelt to development. Now Ford was sidestepping his vow. The rezoned land included 15 different plots in Pickering, Hamilton, Vaughan, and Markham. McIntosh wondered: What had made him do it? And why these parcels of land in particular?

McIntosh joined The Narwhal in 2021, when it launched its Ontario bureau to help cover its environmental policy beat. Before that, she’d reported on the environment and provincial politics for Canada’s National Observer. She knew there was more to the story. That night, she stayed in the office long after everyone else went home. The government had released maps showing which parcels of the Greenbelt it wanted to remove. McIntosh studied the images, looking for answers. She texted her partner at 5 p.m. to let him know she was coming home in 15 minutes, but she wouldn’t actually leave for another two hours. It was late, but she wasn’t budging.

Developers must have played a role in the decision, McIntosh’s experience told her. She was especially curious about the earmarked land in Pickering’s Duffins Rouge Agricultural Preserve. She pored over the maps until something clicked. “I was staring at a chunk [of land] in Pickering. And I was like, I know what this is. And I know who owns it,” she remembers. The development company who owned some of the parcels of land there was a regular PC donor. She began pacing around the office. The Narwhal was an independent publication with 22 staff, with only three at the freshly launched Ontario bureau. To pull off an investigative story as complex as this, McIntosh knew the story would come together faster and better if she had help.

In recent decades, investigative journalists have exposed all sorts of political and social wrongdoing. Perhaps most notably, in 2013, the Toronto Star broke the story about then-Toronto mayor Rob Ford’s crack cocaine use, which revealed a deep pattern of misconduct and eventually led to his being stripped of his mayoral powers. Then there was The Globe and Mail’s 2017 Unfounded investigation, which showed that one in five sexual assault cases in Canada was dismissed as groundless. The investigation led law enforcement agencies to review more than 37,000 previously closed cases.

Big stories like these eat lots of time. The Globe team spent almost two years researching Unfounded before it was published. Freedom of Information requests, so integral to many such stories, can be prohibitively time-consuming and expensive. In fall 2021, Robyn Doolittle, then a member of the Globe’s investigative team and lead reporter on the Unfounded series; and Tom Cardoso, another Globe investigative journalist, began working to create the paper’s Secret Canada project—evaluating the accessibility of Canada’s Freedom of Information processes. It discovered that Ontario takes the longest—an average of 122 days—to process requests. Roughly half of all FOI requests in Ontario are made to the Ministry of the Environment, where the average time to close a request is 216 days. Saskatchewan, meanwhile, has the fastest average processing time, at 20 days. According to Doolittle, now the Globe’s corporate law reporter, delaying is a huge issue only eclipsed by governments overusing redaction. “The big picture of what the Secret Canada investigation found,” she says, “is that from coast to coast, governments and public institutions in this country are routinely breaking access to information laws. They are doing it with complete impunity.”

It doesn’t help that the money isn’t flowing into journalism outlets like it used to. Postmedia, one of Canada’s leading telecommunications and media companies, is laden with debt. Metroland Media Group owes $41.6 million to its parent company, Torstar Corporation, as well as $16 million to terminated employees after filing for bankruptcy in September 2023. Newsrooms are shrinking rapidly. Between 2008 and 2023, more than 500 local news operations closed in 344 communities across Canada, according to the Local News Research Project’s latest report. And public trust in the media is declining in Canada. Less than 40 percent of English speakers trust the news, according to the Reuters Institute 2023 Digital News Report. This makes for a tough landscape in which to produce ambitious journalism, let alone investigate possible government wrongdoing. The stakes are high, though, so McIntosh had to get creative—and collaborative.

It’s not unprecedented for news organizations to team up. Back in 2016, for example, the Star partnered with more than 100 newspapers and television news organizations across 76 countries to investigate the Panama Papers, 11.5 million leaked financial and legal records that exposed a worldwide system of crime and corruption. Recently, three U.K. outlets, The Times, The Sunday Times, and Channel 4’s Dispatches, teamed up to investigate rape allegations against comedian and actor Russell Brand. Each time, journalists eschewed competition in favour of public interest and getting the story right.

Journalists can team up for any number of reasons—combining financial resources, expanding the reporting team, accessing databases, and pooling reliable sources. McIntosh collaborated twice before with the Star’s investigative team and its editor, David Bruser. While she was at the Observer, they’d worked together on a story about Ontario’s Highway 413, which revealed that developers who financially contributed to Ford’s election campaign owned some of the land parcels being rezoned for the highway. She thought Bruser was a thorough editor and a good match for this investigation. When it came to the Greenbelt, McIntosh knew the investigative team had the skill set, access to crucial databases, and the resources to tell a story of this magnitude. With the blessing of her editor, Denise Balkissoon, at The Narwhal, she contacted him. By the next Monday a team had been formed.

McIntosh and the Star’s investigative team—the I-Team—worked around the clock to figure out who owned the land being opened for development. When reporting the Highway 413 story, McIntosh created her list of public donations by developers who benefitted from government decisions, of which the Progressive Conservative Party donors had the largest share. McIntosh put in 12 to 15 hours a day. She says she resembled a “goblin” working at her desk, wearing her favourite oversized sweatshirt while coffee cups and takeout containers piled up around her.

Meanwhile, the Star was also digging. Bruser assigned Kennedy, Javed and McIntosh to research property records on GeoWarehouse, a web-based property information source. The result was a massive spreadsheet that showed which corporations and subsidiaries owned the land set to be removed from the Greenbelt. Javed wrote copy, fact-checked, and followed up with sources, building a deep knowledge of Ontario’s municipalities and their politics through the research she has done reporting on the Greenbelt. It was almost her unofficial beat. “It was a thrilling experience,” she says of their two-week immersion. “We did feel the pressure. You’re working really fast. You feel: Oh my god, that competition!”

The Narwhal and the Star published their investigation on November 17, 2022. It revealed that several developers owned properties that are located within the Greenbelt land that was now open for development, and included a map created with the data Kennedy helped cull. In the four years since Ford was elected, developers had spent millions purchasing Greenbelt land. One, Michael Rice, had bought land in King Township in September, just before the announcement, for $80 million.

While no other publication made a connection as in-depth this fast, the joint investigation sparked other outlets to start breaking the story wide open. McIntosh knew there was much more to learn. Certain developers may have owned Greenbelt land, but were they tipped off about the Greenbelt changes in advance? Who was Ford listening to? Somewhere else in Toronto, another reporter was wondering the same thing.

There are two reasons why Charlie Pinkerton will never forget Ford’s August 2022 press conference in Dundalk, Ontario. One, back on that sunny day, Ford comically swallowed a bee. And two, it was at that press conference that Pinkerton, who was then a reporter at the political news subscription service Queen’s Park Briefing, a subset of iPolitics, received a tip that Ford had held a so-called developers’ party at his house the night before. Months later, when he heard the Greenbelt announcement, Pinkerton had what he calls a “Holy shit!” moment. In the days that followed, he thought of the developers’ party and thought it was all non-coincidental.

Pinkerton told Jessica Smith Cross, editor in chief of iPolitics and Queen’s Park Briefing, that he wanted to investigate the tip. In October, he filed a FOI request for Ford’s calendar from the period June 2 to October 12, 2022. A couple of months later, he filed a separate request for any communications to Ford on August 11. While he waited for them, he kept writing other stories. By January 19, 2023, Pinkerton had received the information he needed. Ford’s calendar on August 11 was labelled as a block—a section of time booked for commitments not kept on the official calendar. There were no records of communications to the premier that day. Pinkerton knew he had something here: Ford had been absent the entire day of the party.

Pinkerton soon learned from one of his sources that Ford had held a stag-and-doe for his daughter and soon-to-be son-in-law in August 2022. He tracked down the name of Ford’s daughter’s wedding photographer and visited the website. There, he found a photo that showed the wedding’s seating chart. With the help of a colleague, Pinkerton was able to produce a high-resolution image of the chart—and the names of 250 attendees. Now, he knew that some of the guests at the wedding were the same developers who owned parcels of the land removed from the Greenbelt. And that two of them had been seated at the premier’s table.

By January 25, Pinkerton had almost finished writing a draft of his investigation. It was time to contact Ford for official comment: Were the developers present at the party, and did they have any influence on his decision to open the Greenbelt? Ford’s office responded with a generic statement. Instead, Ford filed for an “opinion” on his actions with the integrity commissioner, who he said “cleared” him of any impropriety before his office returned comment to Pinkerton. In February, Ford told reporters that the accusations about the stag-and-doe party, which he called a “personal matter,” were “ridiculous.”

Then, some bad news: the owners of iPolitics had caught wind of the story and didn’t like it. iPolitics is co-owned by Paul Rivett, who is executive chairman of GreenFirst Forest Products Inc., a lumber production company, and Brian Storseth, a former Conservative Party caucus member. The company answers to a board of directors—Geoff Wright, Ryan Adam, and Storseth (though Adam and Wright say to the Star that they left the board before this incident). Smith Cross says iPolitics publisher Laura Pennel called her to convey that ownership had read the story and would not allow it to be published. They felt the story was too long and, “more alarmingly” to Smith Cross, wanted to remove certain facts—facts that were clearly in the public interest, according to Smith Cross.

Pinkerton was both shocked and disappointed. On the morning of February 8, Smith Cross spoke with Pennell to try to convey the gravity of ownership’s interference. By then, the story had been ready for weeks and she and Pinkerton felt confident in the reporting. But they couldn’t come to a resolution. Pinkerton was frustrated and felt the decision to hold the piece was ethically unsound. He decided he wouldn’t be complicit. So did Smith Cross. On the evening of February 8, after attempting to reach out directly to the owners without success, Smith Cross resigned. Pinkerton did as well, tweeting that he “resigned on a matter of principle.”

Word travelled fast, and Pinkerton says editors began contacting him. Bruser, the I-Team editor, landed the story Pinkerton was sitting on, and the Star published it on February 10, 2023, with Javed sharing the byline. It had been a long road to get the piece printed, but for Pinkerton it was just the beginning. Shortly after he left iPolitics, he began working at The Trillium, a new Village Media publication with a mandate to cover Ontario politics. While there, he ended up continuing to investigate Ford’s connection to the Greenbelt developers—and collaborating with other publications like The Narwhal.

On a winter night, McIntosh and Pinkerton stood on the fire escape of their favourite Toronto dive bar, convincing each other of their sanity. Shivering in her long black coat, McIntosh was stressed. She and Pinkerton had worked alongside each other at Queen’s Park—he for iPolitics and she for the Observer—during the pandemic. Now, in 2023, they were at different publications, both reporting on the Greenbelt. It was one of the biggest stories of the year. In January of 2023, Jessica Bell, NDP MPP, held a rally in opposition to the decision, and advocacy groups like Ontario Greenbelt Alliance and Greenbelt Advocates were holding rallies, too. But Ford still hadn’t admitted to any wrongdoing, and journalists had yet to uncover proof that he had bypassed ethics to help pals make more profit when it came to backtracking on his original promise not to touch the Greenbelt. McIntosh told Pinkerton that she felt a tremendous amount of pressure to find the truth. She suspected that the missing answers could be found in the government’s communications paper trail. FOIs had served her well in the past—she had been filing at least two every Friday, as she’d been advised to do by Doolittle. Now, she filed FOIs for any files regarding the Greenbelt originating in the premier’s office and transmitted to the housing ministry from August until the November 4 Greenbelt announcement. Such communications, she thought, might reveal how and why they chose the specific parcels of land.

In April 2023, The Narwhal published a story that underscored how the refusal violated the public’s right to know how and why these parcels of land were chosen for development. Some of McIntosh’s FOIs were successful. She discovered that for more than two years the Ontario government had effectively muzzled the Greenbelt advisory council, which was responsible for providing advice to the minister on land use planning matters related to the Greenbelt. At one point, the council comprised 12 members, but seven resigned over the Greenbelt announcement. Typically, the council met 10 times a year and produced public reports on the Greenbelt, but its output trickled in the latter part of 2020. More than half the council resigned that year. In 2021, the government made the Greenbelt Council’s advice, which could include reports, confidential. The council only addressed the public once, referring to former Mississauga mayor Hazel McCallion’s support of the government’s removal of 7,400 acres from the protected area to build homes.

After silence from the council, McIntosh kept digging. Reporters at the Star were still toiling away. The newest addition was Sheila Wang, who joined the I-Team full-time in February 2023, after years of reporting for YorkRegion.com. For the Greenbelt story, Wang and colleagues reached out to dozens of sources to verify who purchased the land, when, and why. Some sources were interviewed and others responded with PR statements. Sources directed her to their company’s legal departments. Wang kept calling and digging for documents anyway. She was one of several journalists across Ontario who kept at it through spring 2023.

Put together, the journalists’ stories showed a network of close, inappropriate connections between certain developers and the politicians who played important roles in delivering the Greenbelt decision. Through June, Pinkerton wrote story after story in The Trillium. He discovered that, in 2020, Ford’s principal secretary, Amin Massoudi, and former cabinet member Kaleed Rasheed visited Las Vegas at the same time as developer Shakir Rehmatullah, who stood to benefit financially from the Greenbelt land swap. Thanks to the reporting, public pressure and political opposition was mounting.

By July, it wasn’t only journalists investigating. Then auditor general Bonnie Lysyk summoned two developers to provide records and be interviewed about land they owned that had been approved for development. Lysyk announced her audit and consequent probe on January 18, 2023. Journalists from The Narwhal, the Star, and The Trillium kept reporting, while on February 23, NDP leader Marit Stiles filed a complaint with Integrity Commissioner David Wake’s office, accusing Ford of impropriety. To avoid the probe, the developers opted to go to court, where they argued that the summons overstepped the auditor general’s authority to scrutinize provincial government finances. Lysyk was not able to question them prior to finalizing her report.

On July 25, McIntosh, Javed, and Wang published The Narwhal/Star report that showed how developers, including Silvio De Gasperis, had paid a total of $173 million in June to buy hundreds of acres in Duffins Rouge. The land was set to increase in value because of the Greenbelt decision. According to the report, the De Gasperis family, their companies, and senior staff had donated at least $294,000 to the Conservative Party since 2014.

On August 9, Lysyk released a 95-page report about the Greenbelt decision. It confirmed and built on what journalists had been reporting for months: that several developers had used their close ties to Ford to influence which parcels of land would be removed from protection. In the years leading up to and following Ford’s election, they had bought up chunks of the Greenbelt in anticipation that they would no longer be protected. This was land, particularly in Duffins Rouge, that could make them a lot of money if opened to development. Lysyk further found that the housing ministry’s chief of staff, Ryan Amato, had helped a small group of developers influence the decision-making process—and that the department’s minister, Steve Clark, had failed to properly oversee the process. Ontario’s politicians, and the rich developers they were in contact with, were set up to exploit provincial zoning processes for their own profit.

On August 22, Amato resigned. Three days later, Sheila Wang published a story in partnership with Javed about Shakir Rehmatullah, president of Flato Developments, who attended the stag-and-doe. The government issued a special zoning order to allow Rehmatullah’s company to build housing on farmland in Markham, north of Toronto. It even expedited the process so construction could begin sooner, though no homes were ever built.

On August 30, Ontario’s integrity commissioner published a report stating that Ford had explicitly instructed former minister Clark to open land in the Greenbelt to development in the interest of developers with whom he had a “private interest.” Clark resigned on September 4. Kaleed Rasheed, the MPP for Mississauga East-Cooksville—and one of the politicians Pinkerton had exposed as being a part of the Las Vegas trip—resigned from Ford’s cabinet on September 20.

Finally, on September 21, in Niagara Falls, Doug Ford stepped up to a lectern emblazoned with the slogan “Building Ontario/Bâtir l’Ontario.” Members of his party’s caucus, dressed sharply and wearing stern faces, stood behind him. “I want the people of Ontario to know I’m listening….I made a promise to you that I wouldn’t touch the Greenbelt. I broke that promise and for that, I’m very, very sorry. Even if you do something for the right reasons, with the best of intentions, it can still be wrong.”

To the reporters who’d worked on the story, Ford’s apology was worthy of skepticism—especially the part about his intentions being pure. McIntosh and Pinkerton’s work wasn’t done yet. They decided that, despite his central role in the scandal, the public didn’t know much about Amato. Together, they wrote a profile to be published in The Narwhal and The Trillium shortly after Ford’s apology, detailing his work for the Ontario Progressive Conservatives with Patrick Brown and Caroline Mulroney, his family’s high-level connections to the Ontario Provincial Police and his personal real estate history.

In October, the RCMP announced its official investigation into the mishandling of the Greenbelt. Six days after the investigation was launched, Ontario’s current housing minister, Paul Calandra, introduced legislation to return all 15 parcels of land to the Greenbelt. McIntosh and the other journalists reported on it all. After more than a year of investigation, McIntosh knew it was important to keep the big picture in mind. “As a society and a province,” says McIntosh, “how do we grow—and learn—from the scandal?”

Ford continued to deny his and his office’s involvement in the scandal.

In January 2024, Duffins Rouge is quiet. The air feels fresh. Moss and mushrooms grow along thick tree trunks, some of which are beaver-chewed or wood-pecked, others laid to rest across the banks of babbling brooks. Close by are stretches of plowed earth, where flocks of geese graze. The land is punctuated by patchwork barns and rusty silos, and at the entrance of the lots, old-fashioned mailboxes stand next to yard signs that read “Doug Ford: Keep Your Greenbelt Promise” and “Hands off the Greenbelt.”

There are also plots of land flattened for housing in the Whitevale Road area, just on the border of Duffins Rouge, where much land was removed from the Greenbelt for development in the November 2022 decision. Pegs mark out plots like makeshift tombstones. Wooden skeletons of three-storey duplexes squat in a row, surrounded by orange construction fences and mounds of dirt. They have their own yard signs, labelled with the slogan “Live in nature’s embrace.” Above it all, birds fly free.

*This article was updated on 04/21/2025 to amend inaccuracies in the initial version published in spring 2024. It corrects several details in the reporting timeline and interactions, such as when McIntosh’s and the Toronto Star’s dedicated investigative team was formed. Several factual details from the Greenbelt story itself, such as ownership of the Pickering land, have also been clarified. For transparency, an earlier version of the article can be viewed here.*

About the author

Daysha Loppie is a fourth year undergraduate student in the journalism program at Toronto Metropolitan University. Her work has been published by the Toronto Star, West End Phoenix, ByBlacks and The Local. She’s interested in long-form feature writing and primarily covers Black communities, social justice, business, arts and culture.