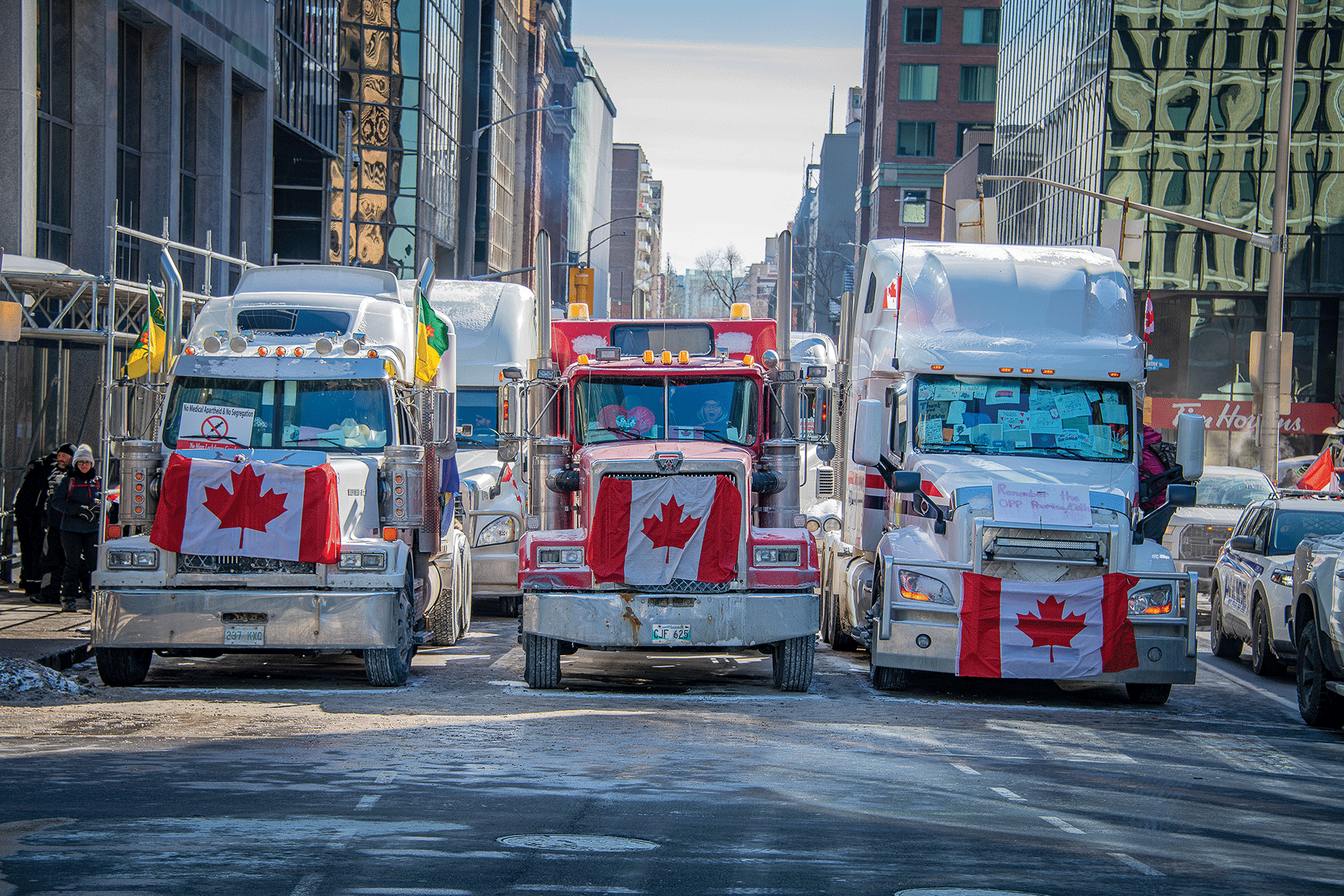

The “Freedom Convoy” overtook downtown Ottawa last year. On the fly, reporters sorted fact from misinformation while the protestors called them liars

Near the end of February 2022, Alex Ballingall, an Ottawa bureau reporter for the Toronto Star, gets word of a gathering of “Freedom Convoy” protesters displaced from downtown Ottawa and now holed up in a small town called Arnprior, about 70 kilometres west of the capital. After 40 minutes of driving, he finds himself on a rural road and sees a field with a few dozen pickup trucks, some porta-potties, and a tent or two. His breath hangs in the air when he rolls down his window to ask the young woman at the entrance if he can speak to a few people, ask a few questions. Concerns have been raised about the possibility of the protestors returning to Ottawa, and it’s Ballingall’s job to find out.

Ballingall explains that he is a journalist, and the woman in the entryway asks who he works for. “The Toronto Star,” he replies. She tells him he is not welcome. Ballingall looks over at a van with a CBC logo parked on the side of the road. He realizes she’s a screener, deliberately picking and choosing which media she’ll allow into the makeshift camp. Not one to back down easily, Ballingall drives around the countryside knocking on doors. Eventually, he sees a small dwelling with a pickup truck adorned with a flapping Canadian flag, a telltale sign of a convoy supporter, parked in the driveway. Ballingall knocks and introduces himself, hoping to ask a few questions.

“You’re the fuckin’ devil!”

Ballingall stares intently at the man standing in the doorway—he isn’t aggressive, but he is not pleased. Both men shiver in the cold as they stand on the porch. Despite this rough start, the conversation goes smoothly. Ballingall listens intently, not bothering to record the conversation. He chooses to interact with the man not as a journalist, but as one human to another. He listens with purpose, still looking the man straight in the eye, asking him questions. At one point, he is even invited inside. By the end of their chat, Ballingall gets an apology for the harsh words he received earlier.

Fast-forward to October 2022, when Ballingall begins to cover the Public Order Emergency Commission’s national inquiry into the implementation of the Emergencies Act. His 10-, 11-, sometimes 12-hour days are full of hearings, interviews, and filing stories before he returns home to his pregnant partner and their two-year-old daughter. He maintains this schedule for a month and a half, until the inquiry climaxes with a public grilling of the prime minister.

With a story this convoluted and controversial, frustration comes with the job, but Ballingall says he tries not to let the pressure get to him. “In some ways,” he says, “we are seeing the history of this episode—of the historic implication of the Emergencies Act, and how that history will be understood and interpreted for posterity—play out in front of our eyes.”

James Bauder avoided talking to some big media outlets. They slandered him, he says

As the world fought an ongoing pandemic, another battle emerged. The Misinformation, disinformation, conspiracy theories, and anti-government propaganda spread rapidly, and many journalists did their best to fight against it. “I wish people would understand,” Ballingall says, “that no one tells us what to write or how to write it.” His coverage, he continues, has been free of external influence. “There is no conspiracy to craft a narrative for any reason with the government, ever,” he says. “If that were to happen, it would be a shocking and appalling scandal, which would probably be exposed by the media.”

However, trust in media is at an all-time low. A 2022 report by Reuters found that only 42 percent of Canadians trust the news they receive. (Please see Chelsea Birks’s story, “Good Vibes Only,” page 96.) The same report also found that only 29 percent of Canadians believe the media are free from excessive political influence.

While legacy news outlets have their own subtle (or not so subtle) political leanings, the journalism industry has shifted away from the traditional goals of objectivity toward more realistic and attainable standards. Transparency, arguably, is the priority, rather than a complete lack of bias. While many convoyers have attacked the media for favouring one point of view over the other, Ballingall says there is something to be said for not giving voice to false information. “You can’t treat things that are verifiably false with the same level of legitimacy as things that are either strictly opinion-based or actually factual.” Constantly juggling the tasks of avoiding bias, achieving full transparency, and fighting the spread of misinformation is not easy. During the convoy, the media were constantly under attack for having their own agenda.

A Convoyer’s Take on Media

James Bauder, a truck driver from Alberta, is in British Columbia, wrapping up his latest protest mission. It’s mid-January 2023, almost a year since the Ottawa protests. He is on his way to pick up Joey and Fancy, two Pomeranian puppies, a gift for him and his wife to try to help alleviate some of the stress they have both faced. Bauder’s name came up often in the media throughout the unraveling of the protests. “We taught Ontario how to convoy,” he says, recalling his involvement in the event.

Bauder’s first experience convoying was in 2018, after he formed Canada Unity, a group that protested COVID-19 measures during the national convoy, and travelled from Calgary to Ottawa. While on the road, he met Patrick King for the first time in Red Deer, Alberta. King had a large social media presence during the protests and was already well-known for his right-wing activism. He now faces multiple charges for his involvement, including perjury, mischief, intimidation, obstructing police, and disobeying a court order. Although the pair worked together to organize the so-called Freedom Convoy protests, they were not on good terms, according to Bauder. Upon meeting each other in 2018, there was a clash of personalities and the two did not stay in close touch.

But circumstances led to Bauder and King reuniting in November 2021, and they agreed to put their differences aside for the sake of organizing the national event. However, before the convoy even arrived in Ottawa late January 2022, they decided to part ways again. Bauder recalls one specific interview he agreed to do with The Fifth Estate for which, according to him, he was never informed that King, the credited leader of the convoy, would also be involved. “I was pissed,” he says, recalling how it felt to be blindsided.

Bauder says he has lost faith in the media’s ability to convey the whole story, even though he also sees information being spread online that hasn’t been diligently researched. “King calls himself alternative media,” Bauder says sounding irritated. In Bauder’s opinion, the use of this term is problematic as it blurs the lines between subjective and objective reporting. “They don’t have the right training. They don’t have the ethics or the morals…and the discipline in regard to speaking in the neutral zone when you’re writing.”

Bauder says he doesn’t trust journalists, and often avoided speaking to bigger media outlets during the protests because he felt they were “slandering” him. He did, however, make the news during his testimony at the Emergencies Act inquiry. A Star article cited some of his statements: “James Bauder…said he was told by ‘God’ to start the convoy and accused Prime Minister Justin Trudeau of ‘treason.’ He cried multiple times about how he believes the convoy was a worldwide beacon of ‘love and unity.’”

The convoy did not go as he imagined it would, and Bauder scrapped plans to try to organize a reunion a year after the first event. Despite facing criminal charges of his own, he also plans to pursue legal action against those whom he claims have discredited him. Most of all, he’s looking forward to putting these events behind him—after he attempts to receive justice.

To Ignore or Engage

Ballingall says there are methods for dealing with misinformation appropriately, without necessarily favouring one side over the other. However, Alayne McGregor, managing editor of local Ottawa news outlet the Centretown Buzz, says the paper decided to tailor its news to its own audience. “The Buzz tended to have a pro-Centretown point of view,” McGregor says. “We knew that we were going to cover the effects on residents more than anything else. We didn’t feel like we needed to spend a lot of time talking to convoy organizers. We didn’t feel the need to spend a lot of time interviewing someone from Alberta about why they wanted to be assholes in our neighbourhood.”

Alex Ballingall wishes the protesters had understood that no one tells him what to write

Backlash is all but expected in the world of a journalist. For McGregor, choosing not to publish an ad for a YouTube video about anti-vaccination information resulted in a poster being distributed around her neighbourhood accusing her of censorship. The words “THE GREAT Centretown Censorship BATTLE” were emblazoned on a bright orange background, along with McGregor’s photo and her personal interests: jazz music, biking, and CENSORSHIP.

Some media scrutinizers will go to great lengths to tell journalists how they feel. Receiving hate mail is common for some reporters, and for Tonda MacCharles, now the Toronto Star’s Ottawa bureau chief, ignorance is bliss. “I blocked a ton of people,” she says, “and I ignored the hate mail.” She also worked closely with Ballingall while covering the Ottawa blockade and subsequent national inquiry. As for delivering fair coverage, questioning her bias was not an issue, but rather a helpful asset. “If you challenge your own assumptions, you’re going to get a better story,” MacCharles says. One of the main issues for her, though, was delivering information to the public during the national inquiry. “It wasn’t just the six weeks of the inquiry or the oral hearings that we have to pay attention to. We also have to pay attention to the thousands of documents that are being disclosed, the thousands that are not being disclosed, and the legal arguments of the parties which haven’t yet been submitted in writing.”

To Spread or Debunk Misinformation

For journalists, covering a national inquiry can be a big task. The turnaround time for stories is almost immediate and, with the added levels of complexities, it is up to reporters to not only understand but also deliver information as concisely and readable as possible. “This is an inquiry unlike any I’ve ever covered,” MacCharles says. “Public inquiries are not just supposed to be accountability exercises and forward-looking for recommendations. They’re also supposed to be an exercise in transparency.” Regarding the delivery of the information within the inquiry to the public directly and effectively, MacCharles says there is room for improvement.

Much like the complexities of the national inquiry, confusion can lead to misinformation, whether intentional or not. For example, an op-ed by Rex Murphy in the National Post stated that the Emergencies Act was only “half-passed.” This is not true. Murphy argued that the Emergencies Act “never made it to the Senate—a requirement of its legitimacy.” The truth is, after cabinet declares an emergency under the Emergencies Act, both the House of Commons and the Senate have seven days to vote on a motion confirming it. If either votes against the motion, the declaration is revoked. While the House of Commons voted in favour immediately, the Senate chose to debate the next day—and had not made a decision by the time Trudeau revoked the declaration on February 23, 2022. As it was within the seven days, the Senate’s approval was never required. Indeed, semantics seemed to be the game throughout the Ottawa occupation, which has bled into the national inquiry. “I would call that a piece of pro-convoy spin,” says Ballingall, referring to Murphy’s comments, “founded in a misunderstanding of the law, at best, and at worst, deliberate misinformation.”

Because misinformation can spread rapidly online, journalists often play the role of “debunker.” A 2022 study published in Digital Journalism found that tight deadlines often make it hard for journalists to perform thorough fact-checking. Furthermore, thanks to social media, misinformation and disinformation have had a place to thrive. Facebook, for example, harbours a private group with more than 1,000 members called “Ivermectin for prevention and treatment.” The drug’s effectiveness in treating COVID-19 has long been debated. Scientific studies have found that it has no benefits related to COVID-19, yet many believe this to be false. In an image posted on Flickr, convoy protestors can be seen waving Canadian flags while holding a poster that reads: “CANADA FIRST Freedom Ivermectin.” In instances like these, it becomes increasingly hard for journalists to report on topics that are verifiably false, especially when large number of people still believe it to be true.

Journalists have been fighting hard to ensure that news is delivered accurately, efficiently, and fairly. However, navigating news delivery while avoiding the spread of misinformation was a constant battle for reporters during the protests. Many convoyers preached mistrust of media, a skepticism often driven by accusations of bias and censorship. Ballingall at times had to make the decision not to give verifiably false information the same weight as facts in his reporting. “That is why we are getting so many accusations of bias,” he says. “Because we are not treating conspiracy theories and misinformation as legitimate as the truth.”

About the author

Emily Clare Elliott is a second-year Master of Journalism student at Toronto Metropolitan University. She completed her undergraduate degree in Global Development Studies at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario. For her professional internship, she worked at Kingstonist News and had an incredible time reporting on and connecting with her community. She is currently the Chief Copy Editor for The Otter. As well as Taylor Swift, she also loves her cats, who have a TikTok page you can follow @skunklovesham. You can also follow her personal social media @eemily74 on Instagram.