t]Hamilton Spectator columnist Susan Clairmont has told several stories about suicide over the course of her career, including in the recent photo project, Lives left behind. On this week’s episode, Clairmont talks about the experience and responsibilities of reporting on people who take their own lives.

Hear the full interview with Susan Clairmont.

[rev_slider_vc alias=”podcast-episode-4-clip-1″]

(Gary Yokoyama and The Hamilton Spectator)

Nicole's mother, Carol Patenaude, speaks about working with Susan Clairmont to tell her daughter's story.

[rev_slider_vc alias=”episode-4-clip-2″]USING THE RIGHT LANGUAGE:

Language is particularly important when writing about suicide, says the Centre for Suicide Prevention. The phrase “committed suicide” has criminal connotations, and is a carryover from to a time when suicide was illegal. Instead, reporters should opt for plain language like “died by suicide” or “killed themselves.” Clairmont says that when in doubt, she asks the family what terms they’re most comfortable with. The Mindset: Reporting on Mental Health guide also recommends not calling suicide “successful” or attempted suicide “unsuccessful,” and says to avoid phrases like “the coward’s way out.”

More information on suicide and language can be found here.

“How are we going to fix this, how are we going to understand this, how are we going to improve mental health care and suicide prevention if we don’t talk about it?”

-Susan Clairmont, on Pull Quotes

Related Reading:

Suicide Notes (Ryerson Review of Journalism)

How should reporters write about suicide? (J Source)

The Science Behind Suicide Contagion (New York Times)

Reporting on suicide: Panelists debate best practices (Ryerson Journalism Research Centre)

Susan Clairmont: A cop in crisis

Susan Clairmont: Const. Daryl Archer died by suicide. His wife Ashley shares his story

Journalism and suicide reporting guidelines in Canada: perspectives, partnerships and processes

How the taboo against reporting on suicide met its end (Globe and Mail)

Last summer, Susan Clairmont published a long feature story in the Hamilton Spectator about Nicole Patenaude, a young woman who took her own life by jumping off a bridge onto a highway.

Clairmont’s piece, which took months to report and write, looked at Nicole’s life and struggles with mental illness–and garnered a “huge” reaction from readers.

“Lots of people who lost loved ones to suicide wanted suddenly to tell their stories,” said Clairmont. She felt compelled to tell these stories, but couldn’t possibly do that in the same in-depth way as she’d written about Nicole.

So the Hamilton Spectator embarked on a photo project called Lives Left Behind. The paper invited people who’d lost someone to suicide to come to a pop-up studio, have their portrait taken, and share their loved-one’s story.

“I think I was in tears constantly through that whole process. Everyone who came in touched my heart,” said Clairmont, who said many of the participants wanted other families struggling with mental illness and suicide to know they were not alone.

Journalism–and the public as a whole– has come a long way in its openness to talking about suicide; there was a time when news organizations simply didn’t write about it. One of the biggest concerns has been the “contagion effect”–the idea that media reporting on suicide is linked to increased incidents of suicide.

Mara Grunau, executive director at the Centre for Suicide Prevention, says responsible media coverage can play an important role in preventing suicide.

“Historically what has happened is that out of fear of doing it wrong, the mainstream media has not reported on suicide at all…and that’s not helpful either,” said Grunau, who says keeping suicide “hush hush” only perpetuates stigma and fosters a lack of understanding.

–Mindset: Reporting on Mental Health guide

-Canadian Psychiatric Association Media Guidelines for Reporting Suicide

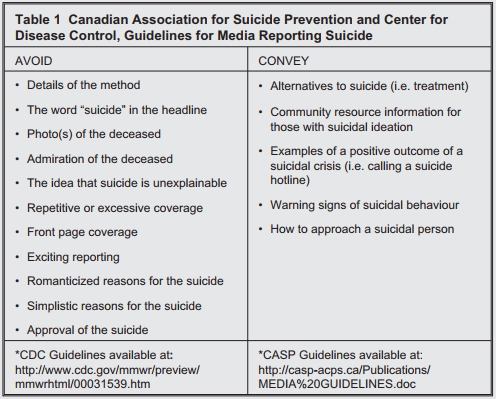

However, she said reporters need to walk a fine line between having thoughtful and open conversations, and sensationalizing or glamorizing suicide coverage.

“We don’t know who’s going to be reading the article. And if someone who’s already at risk of suicide is reading the article and it’s outlining how the person died, what their method was…that can be triggering for that person,” said Grunau, who urges journalists to include suicide crisis line information in all news reports.

Several organizations worldwide have developed media guidelines for reporting on suicide. Psychiatrist Mark Sinyor is the lead author on the updated Canadian Psychiatric Association guidelines, which will be released in the coming months. The last guidelines were published in 2009, however Sinyor says the updated guidelines don’t include any major changes in messaging. Where possible, he said it’s better to write longform articles about suicide that contextualize the issue.

(CPA Media Guidelines for Reporting Suicide, 2009)

New research also suggests media reports about people who seek help for suicidal ideation can have a positive, protective effect. In essence, it’s “not just that suicide is potentially contagious, but that coping is potentially contagions,” he said. Thus, Sinyor says it’s important journalists portray alternatives to suicide. Only telling stories about people who die by suicide can give the wrong impression that suicide is the only option. In fact, he said, the overwhelming amount of people “find paths to resilience.”

André Picard, a health reporter and columnist at the Globe and Mail, has been a vocal advocate for more open reporting on suicide. Picard, who’s been critical of conventional principles governing suicide reporting, helped develop the Mindset: Reporting on Mental Health guide. The guide was written for the realities of the journalistic profession, and urges reporters not to shy away from the topic. Among its recommendations, it advises using plain language, including references to the person’s suffering, and not going into detail about the methods of suicide.

Picard is also skeptical of some of the research behind the contagion effect, which he says is not so simplistic (particularly in an age of social media).

“It was just said as gospel that if you write about suicide people will kill themselves, and that’s simply not true. It’s much more nuanced than that,” said Picard, who was also involved in rewriting the CPA’s updated guidelines.

Reporting on suicide has “changed dramatically” in the last five or ten years, says Picard–a change largely driven by a public shift in attitudes. He doesn’t see as many euphemisms like “died suddenly,” and says there isn’t the same judgement, or fear of “embarrassing people.”

Clairmont said, and she never writes about suicide without the blessing and cooperation of the person’s family. When reporting on people who’ve died by suicide, she’s has worked with their families for weeks or months, so she can truly understand their story.

“How are we going to fix this, how are we going to understand this, how are we going to improve mental health care and suicide prevention if we don’t talk about it?” said Clairmont, who said she’s always pushed back against the silence around suicide.

“There is no shame in mental illness and I don’t think that there’s any shame in suicide either. These are people who in the vast majority of cases have an illness.”

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | RSS