Freelance rates haven’t risen since the 1980s. Meet the journalists who haven’t quit

At the age of 15, Linda Pannozzo sat in the “drench a wench” dunk tank at Canada’s Wonderland, sporting a tunic and an ill-fitting floppy hat, earning $2.90 an hour. It was 1981, and her first summer job. Nearly 43 years, three degrees, two books, and hundreds of research-heavy articles later, she jokes that her job as a part-time theme park employee paid better than being a freelance journalist today.

“I have not made a living from freelancing,” says Pannozzo. “My partner is a teacher, so we just made a decision to live on one income.” This is not to say freelancers can’t make a living, but in Pannozzo’s experience writing longform environmental stories, these features aren’t readily accepted by mainstream outlets, and some independent publications might not have thousands of dollars to spend on important but hard-to-report stories. From 2016 to 2021, Pannozzo worked at the Halifax Examiner and was paid by the piece. “I had a story in there that was 10,000 words. I did not make $10,000,” she says. Her pieces almost always run over 5,000 words, yet the most she’s earned for one is around $2,000. Now Pannozzo mostly writes for her Substack—The Quaking Swamp Journal—where she has paid subscribers, and makes about the same income she did when she was freelancing full time.

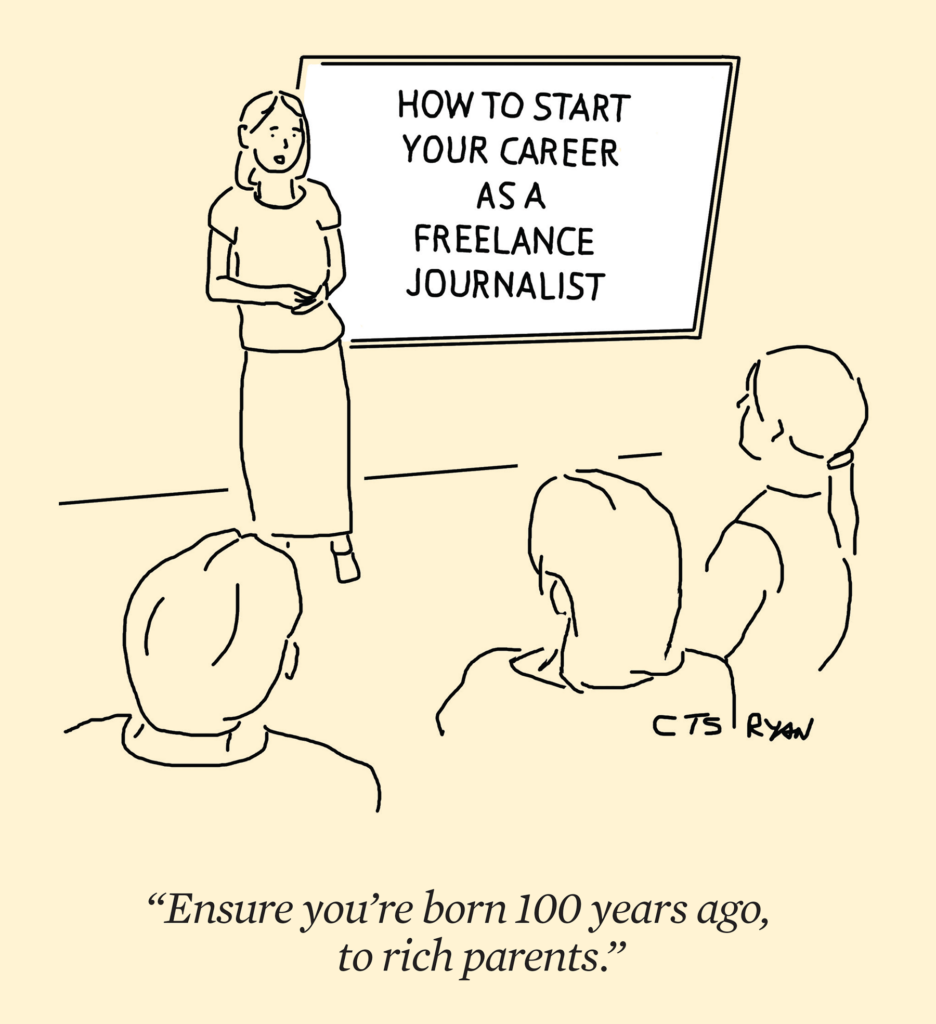

In 1985, milk cost 98 cents per litre and a dozen eggs were $1.37, according to Statistics Canada. The average freelancing rate for an experienced writer was $1 per word. It’s now 2024, and, thanks to inflation, milk costs $2.59 per litre and a dozen eggs are $3.78 at Walmart. The top writing rate is still $1 per word for many, which means freelance wages have been stagnant for four decades. Unless they’re super-negotiators, even established journalists are earning lower rates than when they started, and most early-career journalists aren’t making nearly enough to meet the cost of living.

As staff cuts plague the periodical publications business in Canada and beyond, freelancing, at least temporarily, seems to be inevitable for most magazine writers. Ontario’s magazine industry accounted for 3,572 jobs in 2020, according to Ontario Creates. Between 2016 and 2020, the total number of jobs in the industry fell by 24 percent. Ontario’s periodical publishing industry spent over $207 million on salaries, wages, commissions, and benefits in the year 2021. This was a 44 percent decrease from $369 million in 2013. According to Magazines Canada, every $75,000 in lost revenue at a Canadian magazine publisher will cost one job. In 2023 alone, Ottawa Magazine ceased publication, Popular Science closed its online magazine, and Reader’s Digest Canada, once a household name, ended its course after 76 years in print. National Geographic, with a total reach of just under 28 million adults worldwide, also laid off its team of staff writers, and is continuing as a freelance-only online publication after 135 years in print. Websites once seen as a boon to freelancers have also shuttered recently. BuzzFeed shut down its news division and cut its workforce by 15 percent in April 2023. This January, Condé Nast’s Pitchfork, a culture powerhouse of 30 years, laid off 12 of its employees and was folded into GQ.

George Butters, president of the Canadian Freelance Guild, left the periodical field as his primary source of income long ago. “A magazine I used to write for is paying exactly the same now as it did in 1990,” he says. “There’s no life here, so I started working in television. I like print, but I like making a living as well.” Butters says he became an “entrepreneur” in 1977 and, in 2021, was appointed the president of the CFG, where he helps freelancers navigate the more detrimental forces of technology: AI and inflation. “A lot of people working in the media are afraid to talk about money,” he says. “That’s one of the things we try to help people overcome—giving them techniques so they don’t feel guilty or shy or bad about it.”

Ishani Nath, a freelance entertainment and lifestyle journalist and the former senior editor of Flare, who is currently working full time in communications while freelancing as a journalist, says her decision to leave the publication came a little more than a year after Rogers Media announced it had sold its publishing division to St. Joseph Communications in March 2019. For 40 years, Flare was owned by Rogers, along with Maclean’s, Today’s Parent, Chatelaine, and Hello! Canada. Right before these publications were acquired by St. Joseph, Flare’s masthead was “gutted.” “We went from what felt like a very robust and exciting team to three people, which is impossible. You can’t run a magazine with three people,” she says. “I was there when it was announced that St. Joseph bought Flare and all the other magazines, but I left not long after,” she says. “I was just burnt out.” Nath went back to freelancing—her third round, the previous two before and after a year-long staff job at a smaller publication. By then, she had more experience and a stronger network, but that didn’t earn her more money. “I’m getting paid the same rate I got paid when I graduated, which is nuts,” she says. “It’s been 10 years.”

As Nath was nearing the completion of her journalism degree in 2013, her mother was diagnosed with cancer for a second time. Because of its flexible nature, freelancing was her best option. In the first year, she remembers making very little money. She had no sense of how to freelance—no knowledge of rates, how to pitch different stories, or to whom to pitch. Freelancers are generally expected to figure it out as they go, says Nath. This creates an environment, she says, in which companies could take advantage of hungry young journalists, journalists who don’t know better, or marginalized journalists who care about an issue and want their stories to reach an audience.

“It’s feast or famine with freelancing.

I had to stop—I ran out of money”

By living cheaply, as young people sometimes can, freelancers entering the industry can make it work if they’re frugal. After finishing his undergraduate degree in 2006, Nicholas Hune-Brown, now an award-winning magazine writer and senior editor at The Local, was freelancing occasional feature-length cultural essays for $400 to $1,000, usually in the Toronto Star’s Ideas section. He also played in a band, and wrote and produced plays. He lived with several roommates in a large house near Trinity Bellwoods in Toronto, and paid $520 a month in rent in 2010. Today, an unfurnished room in the same neighbourhood goes for an average of $1,200 per month.

“My overhead was low. I don’t know if that’s even possible anymore,” says Hune-Brown. “The career that I ended up carving out was based on the fact that I didn’t need to make a ton of money for the first few years. I could concentrate on the pieces that felt important to me.”

Hune-Brown got his big break around 2008 when he published a “fun little business story” for Toronto Life about the rise of the “ethnic press.” The story turned into a major investigative piece that went on to be selected for the Best Canadian Essays anthology in 2009. He says editors took notice, and his credibility gave him leverage to do the kind of magazine feature writing he really wanted to do.

Before he was a recognized feature writer, Hune-Brown was paid 50 cents a word for the first piece he ever wrote for the Star’s weekend section. Close to a decade later, the paper’s editors offered him even less.

Inflation is through the roof and pay scales have not increased for freelancers like Nath and Hune-Brown since the beginning of their journalism careers. According to a consumer price index inflation calculator, $1 in 1980 is equivalent to about $3.61 today. This means the freelance rate should be $3.61 per word. Journalism school graduates have inherited an industry where the buying power of a dollar has increased more than 250 percent, but the pay rate hasn’t budged.

KC Hoard, associate editor at The Walrus, graduated from Carleton University in 2020 with an undergraduate degree in journalism and humanities. He interviewed for 20 jobs over a two-year period until he snagged a digital editor contract at Maclean’s, and then finally landed a full-time job with benefits as associate editor at The Walrus in July 2022. While job hunting, he also freelanced for magazines such as Xtra. Even at an average of one to two $400 to $800 pieces a week, he says he was “on the verge of bankruptcy at all times.” The work wasn’t consistent, and he endured periods without assignments or income. “It’s feast or famine with freelancing. That’s the reason I had to stop,” he explains. “I ran out of money.”

Freelancers continue to be underpaid as editors try to stretch as many stories as they can out of a small budget. For nonprofit media organizations like The Walrus or The Narwhal, there’s no well of money they can dig into. “As the editor, I can occasionally negotiate with writers,” says Hoard. “As a former freelancer, I care about writers getting fair pay, but at the same time, there’s only a limited amount of money we have for editorial content.”

Advertising revenue drove the magazine business for a long time. In the nineties, publications started having to compete with a larger variety of media, explains Dru Oja Jay, publisher at The Breach. “In the 2000s, once Facebook and Google started taking over advertising, there was a huge decline in the money going into journalism.” When ad space was no longer valuable, the business model had to change. The Breach’s current business model is based on reader contributions. “The fact is, advertising is what was funding journalism when it peaked in the nineties, and we haven’t made those revenues back,” he says.

Publishers are still trying to figure it out. Some, like The Narwhal, The Walrus, and The Local, have implemented full-time or contract staff writers. Part of the reason for this are federal tax rebate incentives that publishers can get against the salaries of their staff. Beyond a lucky few, most freelancers don’t benefit from these programs, and still need to make ends meet. “We’re in a scarcity framework,” says Jay, regarding both salaries and freelance rates. “We’re trying to get the most impact out of the budget that we have.”

At a typical nine-to-five, people go to their jobs for an agreed number of hours and get paid at regular intervals. Journalists are very passionate. But at what cost?

Hoard says magazine professionals have to be realistic about what this is: a floundering industry that doesn’t have much money and is extremely competitive. Even the brightest and most established compete for limited attention, while navigating financial scarcity. “I killed this idea that I had to be a journalist or else. Journalism is a job. It can’t be your life. If one day I’m not at The Walrus anymore, it would be sad. I love my job, but I have a whole life outside of this. It’s not the end of the world.”