Yellowknife’s Cabin Radio went beyond the call of duty as the Northwest Territories faced its worst wildfire season in recorded history

When the residents of Hay River in the Northwest Territories received an evacuation order as wildfires fast approached on the weekend of August 12, 2023, Cabin Radio changed its approach to covering the story. The Yellowknife-based news outlet switched to rolling live coverage of the fires and evacuations with daily feeds, publishing updates every few minutes from 6 a.m. to midnight for over a month. Residents checked the site or listened to the 24-hour online radio livestream for more updates, deeper articles about the wildfires. Satellite wildfire data, present hot spots and fire lines appeared as added layers atop maps of arterial highways, trails, and telecommunication lines. These were accessible on the Wildfires page, complete with data visualizations of land burned by the blazes, broken down by region. Though this multimedia coverage was important, it was always underpinned by a barrage of traditional news stories, from detailed dissections of person-caused fires and why they happen to interviews with people who defied evacuation orders to feed firefighters.

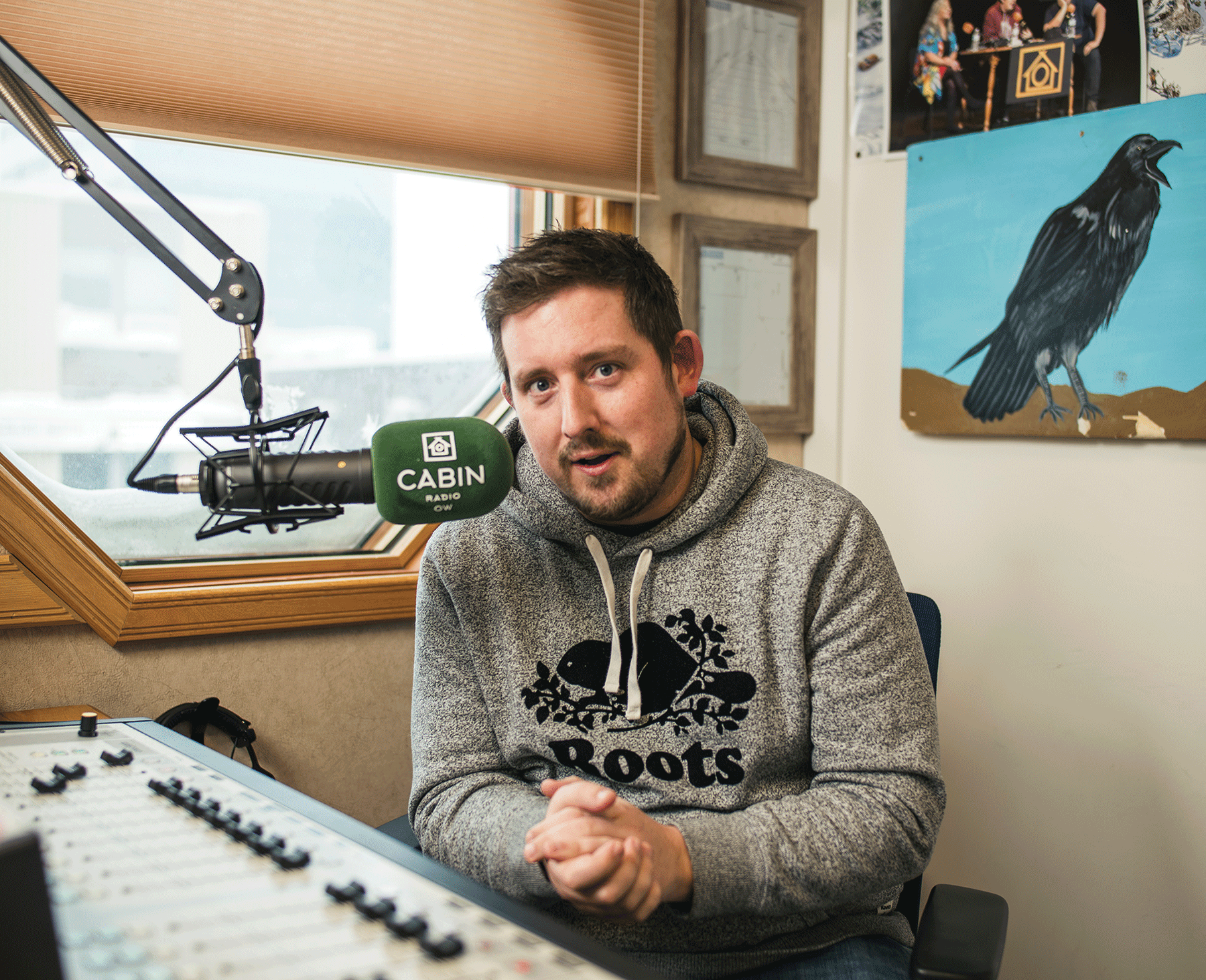

Cabin Radio tackled the 2023 wildfire season with just seven full-time employees—only four of whom are journalists—and two fellows or interns. But many tips and comments came from readers who filled the email inbox, always in triage, or who encountered cofounder and news editor Ollie Williams and his reporters, which helped build its relationship with the community. Cabin Radio’s work—layered, rolling coverage that preserved its local journalism—is a valuable lesson in how to cover natural disasters and the role a small, independent news outlet can play in a crisis.

In 2017, Williams and his cofounders, four other Yellowknife residents, launched an independent, commercial news outlet and internet radio station. The Canadian Radio-television Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) denied the application for a radio licence, saying Yellowknife was too small a market to justify another commercial FM radio station. Unable to enter the FM radio market, Cabin Radio recommitted to an online format that blends lengthy analysis with short, informal updates. It now publishes a yearly average of 2,000 articles, while maintaining a 24-hour online radio stream.

Appealing to Yellowknifers and those from the Northwest Territories, Cabin Radio maintains a strong relationship with its readers and listeners, who are as much sources and subjects as they are neighbours, crossing paths with staff and contributors on an informal basis. Chloe Williams—no relation to Ollie—who was a fellow at Cabin Radio for 13 months that included the 2023 wildfire season, explains that she and her colleagues received emails about how their coverage was saving lives. “There was such an information vacuum,” she says, adding that people encouraged them to stay the course in their coverage.

Cabin Radio joined two established outlets in Yellowknife, each with more staff and more funding to serve the city’s 20,340 residents: CBC North and Northern News Services Limited (NNSL). CBC North is a foundational pillar of journalism in the region. First established in 1923 as the Royal Canadian Corps of Signals to link Yukon with northern and western North America, CBC North was properly established in 1958, growing to encompass all of northern Canada, its radio shows helping to keep far-flung, rural First Nations and Inuit communities informed. NNSL, established in 1972, has six newspapers across the territories, with stories from all publications collected on a single website. The company puts out two Yellowknife broadsheets, the Yellowknifer for community news from the city, and News/North for territory-wide issues.

Bruce Valpy highlights one of the most common challenges with producing journalism in the North: travel costs. In his experience, these are often 30 to 40 percent higher than in the south. “Our Iqaluit bureau was four hours by 737 [airplane] away,” says Valpy, the former publisher and managing editor for NNSL. By the 2010s, however, NNSL had become “very stretched out.” He says Ollie Williams has made the most of these difficulties, taking advantage of rising social media usage and the movement of news to free, online platforms rather than physical publications. A free and agile platform like Cabin Radio was what the North needed, as NNSL’s quality declined due to dropping advertising dollars, he notes, adding that Williams is an “inspired leader.”

An Englishman and former TV and print journalist for the BBC and BBC News, as well as for CNN as a freelance sportswriter, Williams brought his experience with large outlets, where allocating resources means filling a long list of corporate sign-offs. “It isn’t as simple for the CBC to turn the ship around…which isn’t their fault,” he says. “But it demonstrates the niche that a small, independent broadcaster can occupy.” This ability to quickly adapt drove interest in Cabin Radio—and Williams personally—in the depths of wildfire season, with CBC covering the outlet’s efforts as vital to keeping people “informed on the ground.”

Marion LaVigne, cofounder and copublisher of Up Here, a magazine covering and promoting the North since 1984, says that there hasn’t been a new innovator like Williams in the North since the death of NNSL founder Jack “Sig” Sigvaldason. “Ollie has set a new path for journalism up here,” she says. “On the old scoop journalism front, Ollie’s got Sig and his crew beaten.”

Early in May 2023, as the Northwest Territories emerged from a winter that was as much about preparing for wildfire season as it was rebuilding from the last one, Richard Olsen held a press conference to provide updates on the territorial government’s plan for the looming fire season. The manager of fire operations for the territory’s Department of Environment and Climate Change, he emphasized that fire season had begun unusually early and explained the risks and costs associated with person-caused and overwintering fires, while noting some of the meteorological effects that contribute to wildfires. Cabin Radio, NNSL, and CBC North each reported the briefing differently.

“NWT’s 2023 Fire Season Predicted to Be ‘Extreme,’ Authorities Say” went up on Cabin Radio’s site that day. Written by Chloe Williams, it surveyed Olsen’s briefing, offered guidelines to help prevent fires, and broke down concepts like surface fuel and the science of topography’s effects on fire conditions. NNSL’s story, by Jonathan Gardiner, published eight days later—“More Extreme Fires Being Forecasted in NWT for 2023”—offers a summary of the briefing. It emphasized risk and safety, much like Cabin Radio, but got an important piece of information about the previous year’s wildfire season wrong: nearly 600,000 hectares had burned, not 581.

CBC North’s story by Sara Minogue, “Extreme Fire Conditions Have Arrived in the N.W.T., and Could Last until Fall,” summarized the briefing for readers who may not have the context of living in the North. Minogue explained, outlining Olsen’s words, that by northern standards it had been the kind of hot and dry spring that promised a worse wildfire season later in the summer. However, she went on to emphasize Olsen’s statements about “below-normal temperatures and above average precipitation” in certain regions—possibly suggesting a lower chance of wildfire.

As wildfire season progressed from spring into summer, Cabin Radio increased its coverage with the aim of keeping Yellowknife safe and informed. By June, Williams and the team had produced stories about everything from the evacuation of communities near Yellowknife to stories about the services offered by the territorial government that a reader might need to know. “Kátł’odeeche First Nation Evacuated over Wildfire,” from May 14, and “Evacuation Order Issued for Wekweèti over Wildfires,” from June 29, were two of the former. “NWT Launches Online Evacuation Registration Portal,” from June 21, and “How Would Yellowknife Handle an Evacuation? And How Would You?,” from July 27, were two of the latter.

Cabin Radio’s strong daily coverage gave readers the tools they needed to make informed decisions. It also kept them entertained with more light-hearted updates. One was about how many pairs of underwear to pack when evacuating. “It was amazing, all the little bits of information,” LaVigne says. “Some of it useful, some of it just reminders.” She praises Cabin Radio for being lean and mean. “If you want it right away, you’d get it from Cabin Radio,” she says. “You get it from CBC later.”

A long string of crises had prepared Cabin Radio for 2023’s wildfires. “We’ve been through the threat of a territorial government strike with our audience, we’ve been through COVID with them, through floods with them,” says Williams. In addition, the outlet’s ability to remain agile and, as Williams says, quickly “turn the ship,” gave birth to what has earned Cabin Radio the most praise: the layered, rolling, multimedia coverage of all aspects of the wildfires. Traditional news articles that offered calm reassurance, and often entertainment, in the face of the evacuations of the 30-plus communities of the Northwest Territories that Cabin Radio aims to serve, publishing articles with an increasing awareness of the impending disaster. Residents of Hay River, across Great Slave Lake from Yellowknife, who’d gone through three evacuations in two years due to floods and wildfires, could check Cabin Radio for new stories about when an evacuation order might be called and where to shelter when it did. “Hay River Issues ‘Precautionary’ Evacuation Notice,” from April 26, 2023, and “Knowing How Evacuation Feels, Hay River Opens Its Doors to Fort Smith,” from August 12, are just two such stories.

In addition, Cabin Radio’s NWT fire map used satellite data to track hot spots, and the North Slave region’s fibre-optic cable lines to track burn areas, with explanations of how different fires across geography affect the territory. Separate articles broke down the risk to fibre-optic cables and the importance of checking with the relevant authorities and not relying on Cabin Radio alone. The Wildfires page offered a bird’s eye view of wildfires, with an index of all of the outlet’s wildfire stories, a series of Flourish charts—interactive data visualizations—breaking down area burned by region, and resources readers might need. This included social programs and financial supports designed for evacuees, and other wildfire tracking platforms like NASA’s Fire Information for Resource Management System and the Canadian government’s FireSmoke application. The building of digital infrastructure specific to wildfire coverage, while not an overnight effort, was done quickly enough to put Cabin Radio ahead of other Yellowknife-based publications, leaving it better prepared for the staff’s evacuation.

When the evacuation order came in the evening of August 16, the Cabin Radio newsroom scattered in an exodus across Canada. “We reassigned people even as they were being driven to safety,” says Williams, adding how some reporters became specialists in curating pages about the safest ways to evacuate and how to find accommodation and claim financial assistance. “They had the first versions of those pages written and published before even reaching a hotel for the night.”

Rumours of a Yellowknife evacuation had been swirling, even as its neighbouring cities and First Nations reserves were ordered to evacuate, cleared to return, then evacuated again. Though the fires were never close enough before for residents to be afraid, the Hay River’s and Fort Smith’s evacuation orders over the weekend of August 12 let the Cabin Radio team know that it was time to put their plans into action to continue reporting while evacuating.

At CBC North, reporters armed with muscle memory from the COVID-19 pandemic, prepared to confront the crisis head-on despite an apparent lack of planning for a wildfire evacuation. Sidney Cohen, a reporter and editor with CBC North in Yellowknife, says that by evacuating, she felt like she had become too close to the story for a journalist. “You want to be on top of the news and reporting the news as it happens,” she says, “and we really couldn’t in that moment.” Cohen adds, in her opinion, that had CBC North been more digitally agile, it could have kept up its reporting, as Cabin Radio did, during the evacuation. “It’ll be an issue again next summer,” she says.

Liny Lamberink expresses a similar sentiment. An assignment reporter for CBC North who often focuses on climate issues, Lamberink evacuated with her partner, Ollie Williams—yes, the same Ollie—to Fort Simpson. In Lamberink’s view, there was no clear plan for CBC North in case of an evacuation. She says it was “a bit of a mess,” adding that the evacuation was a multiday undertaking for everyone, not a simple one-hour drive to safety. That a stronger plan of action for not just staying safe, but keeping up workflow, would have helped keep stress down.

Chloe Williams, on the other hand, was stressed by the imminent danger of the wildfires, but also by the need to perform, to keep up the work she expected of herself when evacuating. Still feeling like a southern transplant, she had been in Yellowknife for almost a year as the inaugural Wilfrid Laurier Climate Change Journalism fellow, returning to work on the drive. There was work to be done, and it was a way for her to contribute to helping her community as she and her husband, Vincent, took shifts driving the 18 hours to her parents’ house in Canmore, Alberta. “We had got an email that said we were saving people’s lives,” she says. “It was both very encouraging to get those messages, but also very difficult.”

On the drive, Chloe contributed to three guides detailing services available to evacuees as well as filing an “As It Happened” story. One story she wrote from Canmore was about “a bunch of locals who decided to defy the evacuation order” to feed firefighters. She’d learned about them while away from Yellowknife through an email from a Cabin Radio reader. Yellowknifers so preferred Cabin Radio’s coverage during the evacuation that it made news readers out of the most unenthusiastic of residents. “There are people in Yellowknife that hardly ever tuned in to the news,” LaVigne says, “and I know a few of them who became fans of Cabin Radio after the evacuation.”

Despite these successes, Ollie Williams believes Cabin Radio could have done more during an evacuation whose effects are still being felt today. He says that coverage would have been improved by an FM radio licence, as CBC North’s radio shows went on hiatus and many Yellowknifers already rely on Cabin Radio for their news; they also resent the fact that True North FM owner Vista Radio is blocking another media service that residents rely on. CBC North reported in October about Yellowknife’s preference for Cabin Radio, with one source, Brie O’Keefe, who runs the popular @yellowknifememes on Instagram, stating that Yellowknifers are “fiercely loyal” to Cabin Radio for its work during the evacuation.

Williams finds that having all Cabin Radio’s resources committed in one place, few as they were compared to NNSL’s or CBC North’s, is worth it to the improvements they have made to their relationship with Yellowknife and the Northwest Territories. He says, “It’s a constant balance between all the ideas we have, all the things we need to pay for, and how we match up the people, money, and time we have to the many, many things we want to achieve.” Working for an agile local broadcaster allowed the staff to leave town and keep working despite the interruption.

Valpy highlights how Cabin Radio has a strong grip on web journalism, which NNSL previously dominated due to more resources and a lack of competition. In the evacuation, Williams and his reporters filled the void. “Cabin Radio’s rise was consistent with the rise of social media and internet news,” he says.

Despite desiring more funding, bodies, and physical infrastructure, the Cabin Radio team did what local journalists are supposed to do, in and among the community they serve. They spent their days holding conversations with people, engaging with their feedback, or standing up for people who feel Cabin Radio is their court of appeal and a forum to critique government and the handling of evacuations. This strengthened their reciprocal relationship with readers. Journalism in Yellowknife has always felt like a two-way street, says Williams, who praises contributors to the outlet’s Patreon, bringing in some much-needed funding. “I treasure the dynamic we have with our audience so much—it’s rare in journalism, and it’s hard earned,” he says. “We’re incredibly proud of it.”

While an FM radio licence would make Cabin Radio’s work easier and more accessible, it isn’t the be-all and end-all. The outlet aims to continue growing by delivering the news with the integrity, flair, and determination that readers most value. “The support we have means a huge amount,” Williams says. “We’re trying each day to repay that by being the best newsroom for our neighbours that we can be.”

About the author

Sam Jabri-Pickett

Sam is an MJ student at TMU. He’s written for Reuters and Arabian Business. Sam blends modern reporting and historical scholarship in his journalism, telling stories about interesting subcultures and marginalized communities in the Arab World and wider Middle East.