A look at four decades of queer-issues coverage

In the past 40 years, in 63 print issues and many other online-only pieces, queer stories haven’t always been present, but what the Review of Journalism did report on serves as a series of snapshots of where media—queer media—have been, and where they’re going. For our 40th anniversary, the Review is reviewing itself, specifically looking back at our coverage of queer media—what we got right, what we got wrong, and where the Review, and Canadian journalism, ought to go in the future.

The early days of queer media in Canada were defined by The Body Politic. A collective of gay and lesbian writers and journalists produced the monthly magazine whose aim was to amplify discussions of gay liberation and the fight for gay rights. After the Stonewall Riots in Greenwich Village in June 1969, the symbolic birth of modern gay liberation, there was a surge in 2SLGBTQIA+ organizing around the world. “There was no such thing as queer media, in a sense, before The Body Politic,” says Ed Jackson, who joined the collective in 1972, right after the magazine published its first issue in November 1971. “The Body Politic was the first one that was public and intended to be public and visible, and clear in what it was doing.” What it was doing was simple: fighting for gay voices to be heard and gay lives to be respected, though mainstream media did not notice the collective right away, says Jackson.

In 1987, the Review (then the Ryerson Review of Journalism), in its fourth year, took notice of the collective. Michael Totzke’s Spring 1987 feature, “Time, Gentleman, Please,” focused on the last days of The Body Politic. Totzke interviewed members of the collective, many on their way out the door. By the late 1980s, the collective wasn’t thriving financially and, at times, produced radical content that was not well received by mainstream readers. In hopes of maintaining some sort of gay media, Pink Triangle Press, The Body Politic’s not-for-profit parent company, launched Xtra, “a free biweekly guide for gay life in Toronto.”

In 1993, Joanie Veitch’s “Xtra! Xtra!” described Xtra’s growing pains as it became “Toronto’s most popular gay newspaper.” Twenty-four years after Stonewall, 12 years after the Toronto bathhouse raids, and following the birth, life, and death of The Body Politic, being gay seemed a lot more acceptable both in society and in the media. The issue then became the role of a “gay journalist.” The year after Veitch’s examination of Xtra, Tyrone Newhook’s Spring 1994 feature “Coming Out in the Newsroom” explored the struggles—and wins—of gay journalists across the country. “One concern common to both closeted and out gay and lesbian reporters,” wrote Newhook, “is being labelled a homosexual reporter rather than a reporter who just happens to be a homosexual.”

Newhook discussed the exclusion of lesbian voices—still an issue today. In considering the role of a gay reporter in the media, he argued for the benefits of queer-written stories. The late Gerald Hannon, a gay activist, journalist, former Toronto Metropolitan University journalism instructor, and a recurring figure in the Review’s 2SLGBTQIA+ coverage, told Newhook that gay and lesbian journalists might have a different take on stories than heterosexual reporters. “We have been conditioned,” he said, “to view issues and events from an ‘outsider’ perspective: we grew up in a heterosexual society that didn’t have our interests at heart—we learned about straight culture without ever fully being a part of it.”

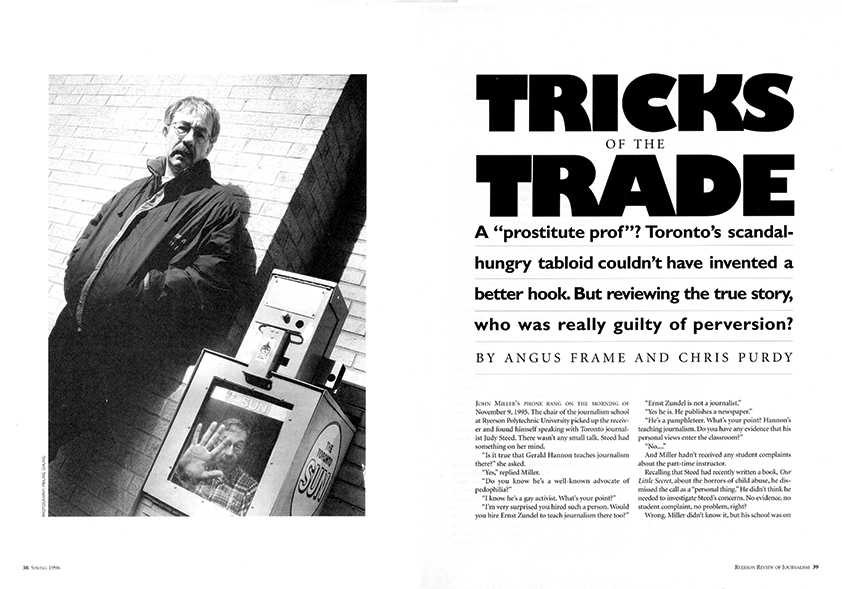

In the following years, Xtra, Pink Triangle Press, and Hannon were consistently present in Review pages. While Hannon was a part-time instructor at the School of Journalism, news broke that he had been supplementing his teaching earnings with sex work. From that, numerous news stories, columns, and features were written. In “Tricks of the Trade” (Spring 1996), Angus Frame presented an in-depth investigation of the Hannon scandal. That same year, the Review published Douglas Cudmore’s “The Little Gay Paper that Grew” (Summer 1996), another story about the status of Xtra.

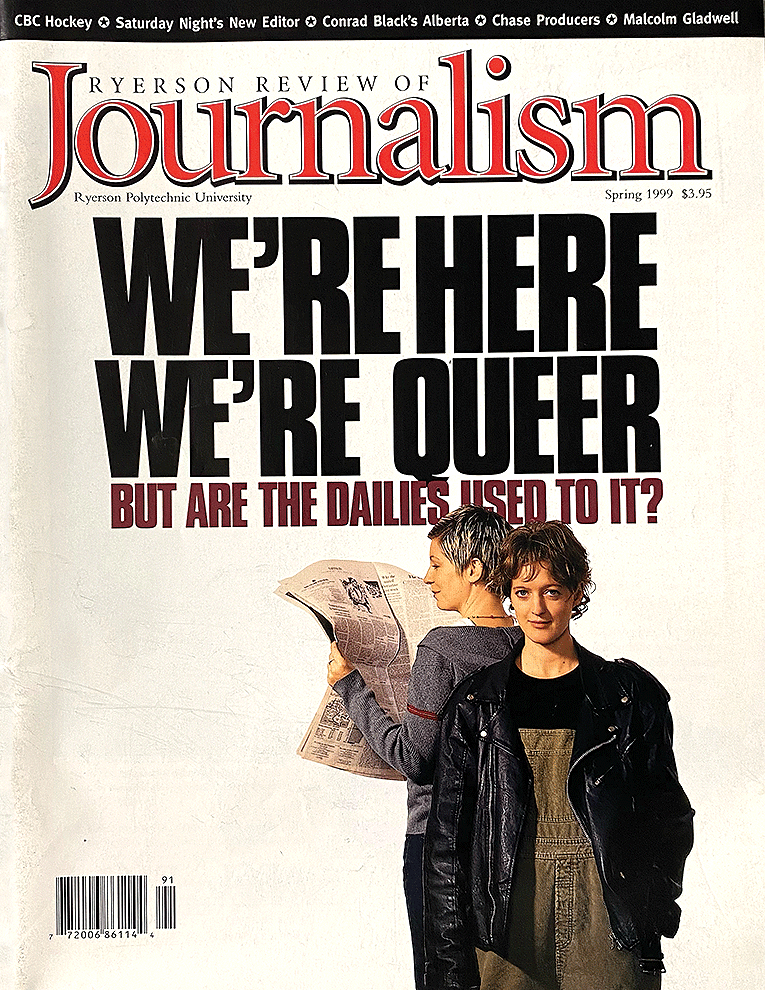

Perhaps one of the Review’s biggest “gay” features was Kate Barker’s cover story, “We’re Here, We’re Queer, But Are the Dailies Used to It?” (Spring 1999), a deep dive into how Canadian daily newspapers report on the queer community. Inspired by The Body Politic and its successor, Xtra, Barker’s Review story questioned why dailies won’t “delve into gay issues with the same zeal as Xtra.” Reflecting on the piece today, she says, “I remember having all kinds of ideas for the Review,” but a “homo tally” on how the dailies covered gay news wasn’t one of them. It was one of her journalism instructors, Stephen Trumper, who gave her the idea for this sidebar. David Hayes, her other instructor, suggested to her, “‘What about doing a data analysis about queer coverage and the dailies?’”

The next two Review features focused on topics that had been mentioned only in passing in previous stories—lesbian journalists and the open use of sex by queer magazines. Samra Habib’s story, “A Talking Contradiction” (Spring 2003), profiled the “feminist, lesbian, Muslim” journalist Irshad Manji, a writer and fierce advocate for reform within Islam, gender equality, and 2SLGBTQIA+ rights. This piece described the struggles of a lesbian journalist of colour who had a successful career despite being constantly pigeonholed. Habib wrote, “To Manji, labels imply that a person is static. They are loaded with connotations that one doesn’t necessarily choose for oneself. Her concern with these labels seems to be that other people’s definitions are not her own.” Two years later, Maya Saibil wrote “Whip It Out” (Spring 2005), about the major gay magazines of the day, namely Xtra, fab, and fugues, and how the they dressed up their articles with “titillating pull-quotes, sexually suggestive headlines, and racy photos.”

Today, Saibil remembers the Review allowing students to pitch stories of relevance and interest to them. “Whatever you’re interested in and going through in your life at that time—if you can pick on any topic in the world, you’re going to pick something that’s meaningful to you,” Saibil says. “At that time, being a lesbian defined my identity in a big way. Because of that, I was interested in writing a feature that related to the community.” The year 2005 was also big for 2SLGBTQIA+ rights, as Bill C-38 became law in the country, giving same-sex couples the right to marry.

In the next eight years, however, the Review did not publish any stories about queer journalism issues. The next in-depth article came with a story about a slice of the 2SLGBTQIA+ community that hadn’t yet made a major appearance in Review pages. “The big hole in my story—it’s trans people, right?” says Barker. “In terms of language, we talked about gay and queer but we didn’t talk about LGBTQ yet.”

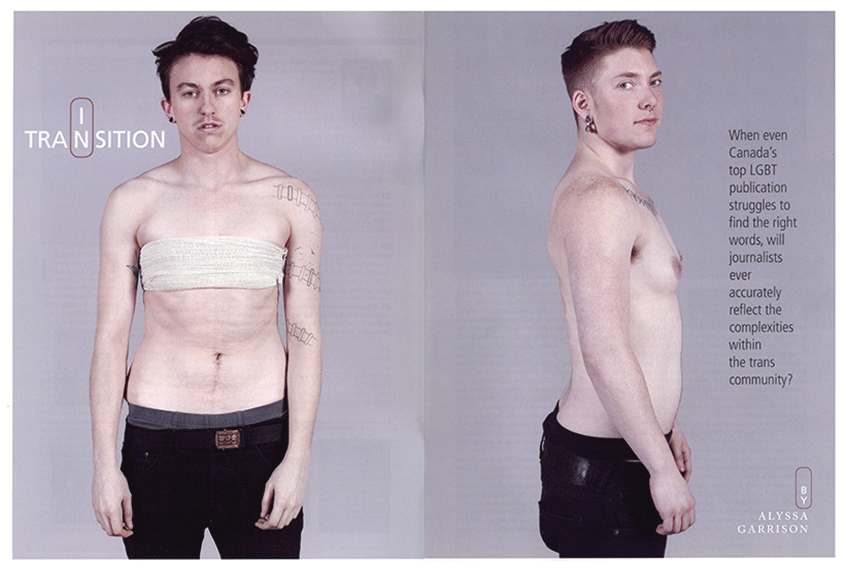

In the Review’s first extensive coverage of trans issues, “In Transition” (Winter 2013), Alyssa Garrison discussed the use of the they/them pronouns in journalism. Garrison, much like Barker in 1999, took an in-depth look into how mainstream and queer media talk about trans people. The prompt for the story was Canadian queer activist and artist Elisha Lim’s request to be referred to as they/them. In 2011, in an interview with Xtra, Lim tried to implement gender-neutral pronouns, which Xtra, at the time, refused. Garrison wrote of the incident, “The disconnect between the media and the community grows larger when even Xtra is out of touch.”

In the years 2016 and 2018, the Review saw even more trans content in print and on its website. In “The Next Frontier” (Spring 2016), Blair Mlotek wrote that the stories of trans people are largely absent in mainstream media. Analyzing media and the Review reporting over the previous three decades, Mlotek found that, in the early days of covering queer communities, gay men’s and lesbian women’s stories were stereotyped as simply about being “gay.” Queer journalists and their allies had to fight to tell their stories over this period. They did, and the journalism industry evolved. Still, trans lives usually boiled down to singular things in the media, especially straight media. “Early reporting on gay issues parallels the evolution of trans coverage today,” Mlotek wrote. “Today, replace ‘gay’ with ‘trans’ and we find journalism gradually developing a more sophisticated—and sensitive—approach.”

In 2018, Luke Elisio wrote “Portrait of a Journalist: Sophia Banks,” the third and most recent Review profile on a 2SLGBTQIA+ journalist. In it, Elisio described a few of Banks’s struggles with something that many queer and trans journalists face—being typecast as a writer for trans issues only.

Most of the Review’s stories about queer reporting narrate a struggle—a struggle to come out, a struggle to write stories, a struggle to publish and print those stories, a struggle to find sources willing to talk, a struggle to write anything but these stories, a struggle to survive as a magazine, a struggle to survive as a journalist, a struggle to get ads and money, a struggle for readers that want more. And the outlet that goes hand in hand with the Review’s coverage of 2SLGBTQIA+ media is Xtra, Pink Triangle Press, its team, and its history. Over the years, the Review has done three features on Xtra, and a few other online pieces, all detailing the history of the iconic Canadian publication from its birth onward. In 2015, the Review mourned the death of Xtra’s print component. Writer and Review alumna Erica Lenti, Xtra’s senior editor, 2019 to 2022, says, “When I found out that the print edition was shutting down, I was like, I need to commemorate it in some capacity.”

The Review, for 40 years reporting on the state of media, often checked in on Xtra as a big player in queer media in the country. “Xtra was born out of necessity, coming out of The Body Politic,” says Lenti. “It speaks to the idea that when a community speaks to you and not for you, you can create some amazing things. Its existence is a testament to the great journalism that has been done over the years.”

After Lenti’s short online obituary for Xtra’s print edition, Sarah Krichel wanted to once again review the state of Xtra, as Canada’s largest queer publication. “I didn’t think that queer and trans news was unwelcomed. Rather, I noticed a gap in it. And I thought that the Review could really use some coverage of what’s going on around queer and trans status,” she says. Krichel wrote the 2019 online piece “Daily Xtra Is Making the Changes Necessary to Keep Queer and Trans News Alive,” describing some of the struggles the publication was going through. “I just loved the microcosm this story was showing for other communities going through similar things.”

The very next year, Xtra returned to the Review’s print edition. This time, Sean Young produced a state-of-the-union piece that looked at Xtra’s entire operation amid substantial editorial changes. In “And Hot Pink All Over” (Spring 2020), Young discusses the recent role of queer media in a world of major human rights movements, such as Black Lives Matter, which brought the 2016 Pride Parade in Toronto to a halt, over demanding respect and intersectionality with the queer community. While doing research for his piece, Young looked back at what the magazine had produced and noticed the through line it has built of queer media history. “It’s like we need an update from this world because nobody else is touching it.” While in journalism school, Young found that many journalists were guided by the principle of giving a voice to the voiceless. “You’re not giving voice to the voiceless,” he decided, “you’re using the connection, the privilege that you have as a person that’s able to be in these spaces, and you should be able to give up that space to someone that wouldn’t have that clearance.”

At times, the Review may seem overly explanatory to readers immersed in queer culture, language, and media, especially when describing the life-changing implications of using the right pronouns and language when referring to queer people. However, when thinking of this magazine’s role and audience, we’ve been doing a fair job. Slowly, but at times faster than most, the Review has criticized bad examples of reporting and celebrated the journalists and organizations that have done an exemplary job—all while giving examples of what and what not to do. This can be attributed in part to the fact that the Review masthead is composed of student journalists who tend to be more hopeful and diverse than staff at most news outlets. Since 2022, the Review has been putting together a yearly diversity report, collecting data volunteered by masthead members anonymously. Last year, 26 percent of Review masthead members who responded to the diversity survey identified as 2SLGBTQIA+. This year, that number rose to 58 percent. But although queer voices have become a mainstay at the Review, beyond the magazine, 2SLGBTQIA+ representation is far less common—the figures remain much lower at mainstream publications like CBC and Global News, as reported in the Review’s 2023 diversity report.

Hearing different and diverse voices is what journalism needs to do, and what queer media have been trying to do. For stories to better represent these communities, their members must tell them. “Having trans people in newsrooms and on mastheads is so, so crucial,” says Lenti. “That’s how the coverage will get better.”

Yes, mainstream media are getting better at telling queer stories, but there’s still a demand for stories by and about queer and trans people. “We’re starting to see more and better 2SLGBTQIA+ coverage than we would have seen maybe 10 or 15 years ago in the mainstream,” says Ziya Jones, former Review editor and current health section editor at Xtra, “but there are still a lot of problems. So, a publication like Xtra, that is specifically dedicated to 2SLGBTQIA+ coverage, and that is made by and for queer and trans communities, is really valuable.”

Jones thinks the next important goal is to make intersectionality a reality in coverage. They don’t see enough queer Indigenous voices, Black Indigenous voices, or enough people of colour in general represented, “just the same way that they are in the wider media landscape.”

Jones’s call for intersectionality may fit well with the Review’s future needs, even if this is not immediately obvious. By providing students with the space to critically review the industry they are entering, the magazine can give young journalists a space to expand the intersectionality of coverage. “It’s good to train people,” they say. “I hope the industry will keep those people, support them, and help them find their place.”

What makes queer media so precious is its ability to connect to its audience, Jones emphasizes. “We’re not speaking to an uninitiated, one-on-one style audience,” they say. “We’re talking to people who are living experiences every day. It’s a space to tell those stories and to reflect those experiences and to do that kind of reporting that you’re not necessarily getting in other places.”

About the author

Mariana Schuetze is a fourth-year undergraduate journalism student at Toronto Metropolitan University. She is the Editor-in-Chief of CanCulture Magazine and works at TMU’s radio station, Met Radio as the Collective Coordinator – so she spends most of her time looking over other people’s work and replying to emails. In her work, she loves to talk about arts, culture and their importance to society.