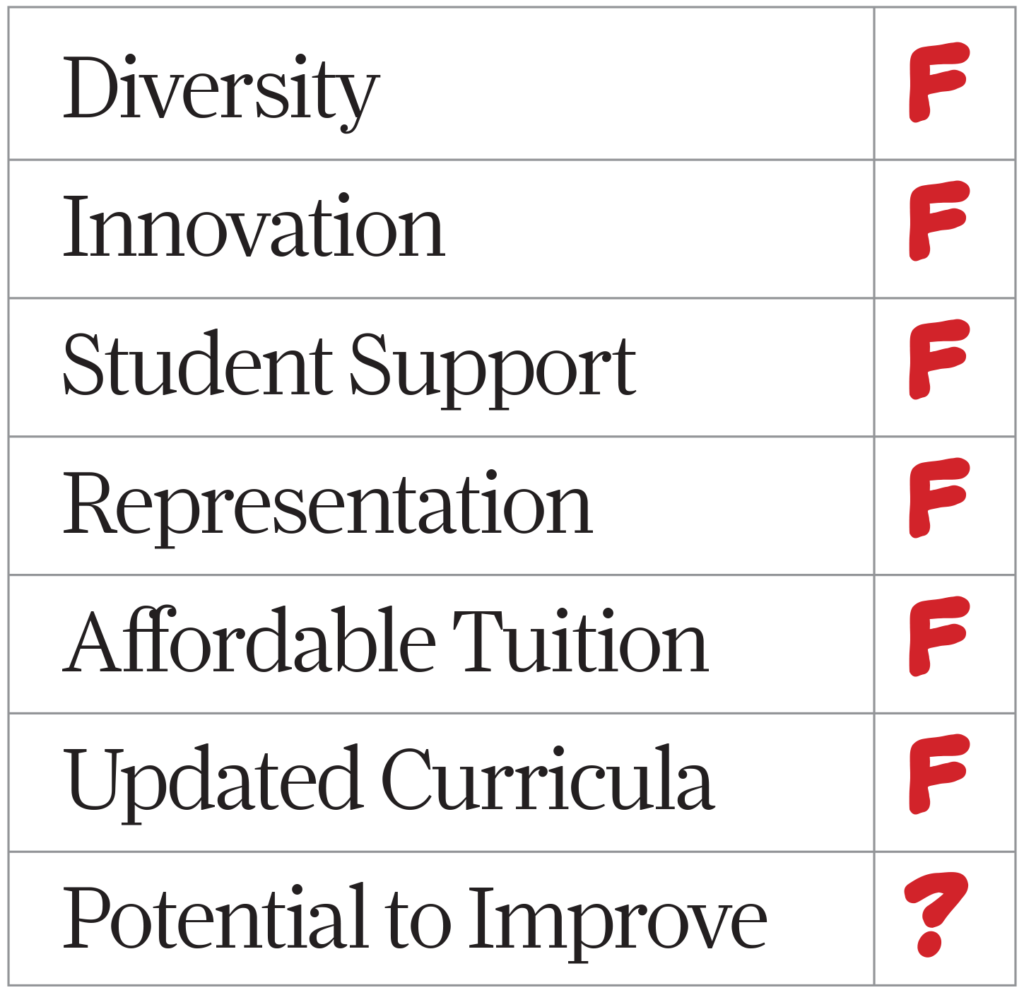

J-schools are inadequately preparing us for the future of journalism—here’s why.

Like many of my peers, I fought hard to get into Ryerson’s prestigious undergraduate journalism program. When I wasn’t initially accepted, I went to Toronto to study liberal arts at Ryerson anyway, wrote for the independent campus newspaper The Eyeopener, and tried to build a portfolio that would put me ahead of the competition. Following my acceptance in 2017 and a solid foundational first year, my experience at school was marred by rigid ideas of what journalism—or a journalist—should be. Joseph Pulitzer had envisioned journalism schools as a hub for improved journalistic practice and ideas. But I found myself trapped in a production factory serving a shrinking industry looking to me and my BIPOC contemporaries to help solve many of its problems.

I wasn’t alone in feeling dispirited. My friend Nathan Sing, who graduated in 2020, had, like me, worked tirelessly to get into the school. He, too, gained a lot of practical knowledge in his first year (how to structure an article and cold-call sources, for example, skills that he still utilizes in his day-to-day life as a freelancer). But the experience began to sour thereafter; he felt increasingly unrepresented in course content as a queer man and person of colour, and as if his ideas weren’t welcome if they didn’t fit the narrow, hard-news-focused curriculum presented to him. He remembers sitting in class, feeling frustrated while watching CBC documentaries from the year he was born, while receiving little instruction on producing broadcast news for a media landscape that looks little like it did in 1998.

As he looks back on his experience, Sing says he spent a lot of time advocating for himself. As an outspoken young journalist, he knows he’s one of the few students who pushes back against barriers; he worries about those who don’t.

In January 2020, the Canadian Association of Black Journalists (CABJ) and Canadian Journalists of Colour (CJOC) released a joint statement addressing the glaring lack of racial diversity in Canadian newsrooms and media coverage, urging news leaders to address the problem “in a meaningful and systemic way.” The statement outlined seven calls to action to help guide Canadian news outlets toward becoming more equitable and representative of the country’s multicultural demographics. The final one was aimed at J-schools: “Start the work of diversity and inclusion in Canadian journalism schools.” They said remedying this lack of representation begins in journalism education, and called upon journalism schools to place more emphasis on “covering racialized communities, providing perspectives from experts of colour, hiring more diverse faculty and developing strategies for recruitment from racialized communities.” In its final 2015 report, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) also addressed the problem: its 86th call to action appealed to journalism programs to mandate education on Indigenous history for all students, including the history and legacy of residential schools. A 2019 Journalists for Human Rights (JHR) report assessed the progress of this call to action in Ontario’s post-secondary journalism and media programs and found that many schools, while making important early steps, “continue to lack adequate programing [sic] to address the TRC calls to action.”

Another concern: Indigenous journalists and past students interviewed shared the feeling of being an Indigenous “spokesperson” while in school, and a number of faculty at these schools reported a “lack of funding and resources to adequately address” the TRC’s 86th call to action. Kyle Edwards, an Anishinaabe journalist from the Lake Manitoba First Nation and 2017 Ryerson graduate, wrote in the report that the lack of courses on Indigenous history and reporting on Indigenous communities resulted in his first quarter of university being “anything but successful.” He would go on to do better. In 2019, the Canadian Association of Journalists recognized him as one of the most influential new voices in Canadian media when he received the JHR/CAJ Emerging Indigenous Journalist Award in 2019 for his work at Maclean’s. He is now the managing editor of Native News Online and a visiting Nieman Fellow at Harvard University.

Anita Li, a media consultant and instructor of Ryerson’s journalism innovation course, says the CJOC, which she co-founded, and the CABJ felt it was important to include that seventh call to action because journalism schools serve as a direct talent pipeline and are intricately connected to Canada’s highly centralized media industry. “It’s not like in the U.S. media ecosystem, where there’s all different types of outlets, there’s all different types of journalism schools with different approaches. There are certain journalism schools that are upheld as the best, Ryerson among them,” says Li. “What we learn in J-schools, and specifically the really celebrated ones, is exactly how we practice journalism in the industry.”

Six months after the CABJ and CJOC calls to action were released, and following a summer of protests against police brutality and anti-Black racism across North America, BIPOC students and alumni of Carleton’s journalism program released a blistering open letter titled “Pushing for institutional change at Carleton University’s School of Journalism,” in conjunction with a petition of support that amassed nearly 5,000 signatures. The letter illustrated the ways in which Carleton’s journalism school has failed to support Black, Indigenous, and racialized students; created an environment where they feel they don’t belong; and deterred them from pursuing careers in journalism.

“The school’s often non-existent approaches to tackling systemic issues within the institution—particularly whiteness, colonialism and racism—create a body of graduates that are ill-equipped to serve the Canadian public,” the letter reads. “If students are not equipped to address systems of oppression within the media and in the world, oppressed and disenfranchised groups will be continually misrepresented through stories produced by graduates of the journalism program.”

The letter included anonymous anecdotes of students’ experiences at the school, detailing incidents such as students saying the N-word in class without consequence, explaining that racism isn’t real, using anti-Indigenous language, and a number of other microaggressions. One anecdote describes an incident in which an international student was told her friend would “struggle to do good work” in radio because of his accent. One student wrote they only had one professor of colour over a five-year education, and another said every professor they had in the program was white. “I suffered so much in that program from the beginning….I was reminded that the school’s faculty did not have the range to understand why it was an oppressive space,” one person wrote.

“Clear reforms are needed if the school wants to be a leader in journalism education, as it consistently claims to be,” the letter reads. “We feel compelled to hold Carleton’s School of Journalism accountable for the issues BIPOC students have addressed many times with the school privately with no success. These conversations can no longer take place behind closed doors.”

The school’s then-current and incoming program heads endorsed the open letter “in principle” and committed to hiring a new chair in journalism, diversity and inclusion studies; redesigning introductory undergraduate courses to centre diversity and inclusion; making an Indigenous history course mandatory; giving guidance to instructors on equitable course delivery; and more.

“But these shifts in direction are less a result of university vision and more a crisis response to student demands. Many students feel heavily burdened and worn out, having put ‘countless hours of free labour and painful work to call attention to our experiences.’”

“We have a responsibility to acknowledge the role we have played in the perpetuation of systemic racism that also exists in our industry at large, and to make sure our students are getting the skills and capabilities they’re going to need to report on the full diversity of Canadian society,” says Allan Thompson, head of Carleton’s journalism school. “It absolutely took too long for us to recognize that. That’s where we failed.”

At roughly the same time, Ryerson journalism students launched a petition to implement a Black-Canadian reporting course in the program’s curriculum that attained close to 4,000 signatures. The school responded swiftly with the announcement of a new course, “Reporting on Race: The Black Community in the Media,” to be taught by bestselling author and Ryerson grad Eternity Martis and offered in fall 2020. The announcement garnered a considerable amount of media coverage and positive PR for the school after the story was picked up by CBC, CTV, Canada’s National Observer, and others. Mirroring Ryerson, Carleton hired CBC News Ottawa anchor Adrian Harewood to teach a new course, “Journalism, Race and Diversity.” Recently, Carleton went a step further, announcing award-winning CBC journalist Nana aba Duncan as the program’s first Carty Chair in Journalism, Diversity and Inclusion Studies—the first position of its kind in a Canadian journalism school, according to Thompson.

But these shifts in direction are less a result of university vision and more a crisis response to student demands. Many students feel heavily burdened and worn out, having put “countless hours of free labour and painful work to call attention to our experiences and what must be done to address the issues we have raised,” as the Carleton open letter’s authors put it.

Students at Ryerson have also found the emotional labour of pointing out and advocating for a coherent, relevant vision to be exhausting. In a piece published in Ryerson Magazine earlier this year, my friend Connor Garel, a Ryerson J-school grad, illustrated how the lack of diversity in the program’s faculty impacted its curriculum.

“The faculty is mostly a blur of white,” wrote Garel. “It’s difficult to summarize the vast and many-headed consequences of this alienation: how it produces a profound sense of imposter’s syndrome, how it makes you feel perpetually out of place, how unwelcoming these rooms feel, how it obscures whatever future you might have.” He tells me that a critical and opinion writing course in his fourth year taught by Vicky Mochama, one of a handful of Black teachers he had, was the first time an instructor understood his work.

“To me, the journalist they want you to become is a white journalist,” says Garel. “That obviously has a profound effect on how valid students feel their own concerns are, and whether they feel they even have a place in this industry at all. You don’t want to feel that way in a place where you’re paying thousands of dollars to learn.”

Sing points to many clashes with the J-school’s administrators throughout his time there. During a meeting of the Journalism Course Union (JCU) between students and faculty in his second year, he got into a yelling match about the curriculum’s lack of queer and racialized voices.

One of Ryerson’s most contentious flare-ups occurred in February. The National Post reported that a fourth-year journalism student had filed a case with the Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario, claiming he had been discriminated against by Ryerson’s independent student newspaper, The Eyeopener, on the basis of his strict Roman Catholic views. (Disclosure: I have worked at The Eye since late 2018.) Jonathan Bradley, who was a volunteer reporter for the paper on an article-by-article basis, was barred from contributing to The Eye after it learned of his public tweets from 2017 that he believes practicing homosexuality and “transvestism” are sins. He is seeking $20,000 in compensation.

On February 5, and after Bradley began threatening to hit other journalism students who criticized his views online with defamation lawsuits, close to 80 J-school students joined the JCU’s 2021 winter meeting with faculty on Zoom and many expressed how they felt unsafe around Bradley, urging the school to take action to protect its marginalized students and publicly denounce bigotry within the program. Faculty members who were present refused to speak on or acknowledge the ongoing legal case. Days later, a thread was posted to the school’s Twitter account at 11 p.m., stating that the school does not support “racism, homophobia and transphobia in any form” and calling for students and staff to facilitate “a culture of mutual respect.”

On the night of March 7, the program’s chair and associate chair, who was also the undergraduate journalism program director, resigned from their positions just hours before students and alumni released an open letter detailing experiences of discrimination and mistreatment, accusing the school of perpetuating systemic racism and of leaving students traumatized and ill-prepared for careers in journalism. (Disclosure: I helped organize and contributed to the open letter and its calls to action.) Days later, associate professors Asmaa Malik and Gavin Adamson stepped up as interim co-chairs while the administration searches for permanent replacements. As soon as they were announced, Malik and Adamson released an action plan, unanimously accepted by faculty, which addressed the calls to action with new measures such as journalism-focused equity training for all staff, hiring two diverse faculty members, the establishment of a permanent student equity task force, and a re-examination and redesign of the curriculum.

“On March 7 Ryerson students and alumni released an open letter detailing experiences of discrimination and mistreatment, accusing the school of perpetuating systemic racism and of leaving students traumatized and ill-prepared for careers in journalism”

Watching the situation unfold online, BuzzFeed News senior culture writer and Ryerson journalism grad Scaachi Koul found it disappointing to hear complaints and experiences nearly identical to the ones she witnessed while studying there nearly a decade ago, where she says she left the program unequipped to cover issues of social justice and had to learn on the job. “It is your job to make sure that your students feel safe at the school. It is your job to make sure that the curriculum is up to date with how the industry and how society functions, and that has not happened,” she says. “What bothers me most about this school is putting students in a position where a bunch of 20-year-olds have to do the work that should be done by the 50- to 60-year-old administrators who are being paid to do this.

“They seem perpetually 10 years behind,” says Koul.

Toronto is among the world’s most multicultural cities; its racialized population is the majority, which is why the current reckoning at the Ryerson J-school is not surprising. Both newsrooms and journalism schools haven’t caught up to these 21st-century realities. Data on Canadian newsroom demographics remain scarce, largely because of media outlets’ refusal to self-report details of their employee makeup, but a 2018 American research paper titled “Expertise in Journalism: Factors Shaping a Cognitive and Culturally Elite Profession,” by Jonathan Wai and Kaja Perina, found that only a handful of elite schools feed The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal, with almost half of those publications’ employees having attended an elite school, and roughly 20 percent having attended an Ivy League school. A 2019 report from Voices, which is the Asian American Journalists Association’s student program, found that 65 percent of summer interns from a group of large media companies—including the NYT, WSJ, NPR, and The Washington Post—came from highly selective universities in the U.S.

Within the hallowed walls of both Ryerson and Carleton, course development is centred on whiteness—what Garel refers to as developing “a white journalist.”

Today’s students don’t reflect the cohorts of the past, and Li notes that they tend to be far more interested in her experience as news director of Complex than her time at The Globe and Mail, Toronto Star, CTV, or CBC, which is why it’s important for her to emphasize her unorthodox past. Out of Canadian media’s small and centralized makeup, an archetype of the “ideal journalist” has emerged and been perpetuated by J-schools, creating a dangerous codependency, which is something very slow to change.

“That,” says Li, “is not very good for innovation, experimentation, and serving communities who might not fit that archetype. It’s strange to even have the archetype in such a pluralistic and diverse country like Canada.”

Many of the strongest reporters I know who came out of journalism school have been pushed further from the field for not adhering to this archetype. Koul, who graduated in 2012, tells me that there are a low number of women of colour from her year still in journalism today. “I don’t think the school equipped their racialized students to work because it functions differently for you if you’re not white, inherently,” she says. There’s no way to quantify the impact of this marginalization on an industry where those in the mainstream have a tendency to look and think like one another, or the impact this has had on alienating its diverse audience.

Freelance journalist Nora Loreto left Ryerson in 2008 after five years, switching her major to public administration and governance once it became apparent she wouldn’t be able to collect her final core journalism credits while working full-time to support herself, since the courses required her to be in class for roughly eight hours at a time. Loreto was familiar with the mainstream image the journalism school projected onto its students back then, too, recalling who went on to become big, successful journalists because “they thought in the right way.”

“They understood the way that the mainstream works and what you have to do, or be, to make it. If you don’t, it doesn’t matter how good your writing is, it doesn’t matter how critical your eye is, it doesn’t matter how good the reporting you can do is. If you don’t fit in, you’re not going to make it because it’s too difficult or frustrating, or no one’s going to help you,” says Loreto. “It’s one more way to narrow the path of who is able to become a journalist in this country, while at the same time there are massive cuts and disappearing jobs.”

Loreto thinks a more inclusive journalism school means a shift in recruitment strategies and approaches. The professionalization of journalism and resulting placement of journalism education in a for-profit education model prioritizes those who can afford to attend, and thus perpetuates the elitist, mainstream news or investigative reporter model, she says. “Good journalism requires average people to be in those jobs. People who have life experiences from working-class backgrounds, parents who may have worked in long-term care, or as a janitor, or driving the bus.”

I came to journalism school with a singular goal: attaining the skills, education, and experience needed to become a working journalist. I didn’t—and still don’t—think that was an unreasonable ask, given that, in return, I would work hard each day to develop my craft and grab onto every opportunity that came my way, and that I, of course, ensured my hefty tuition fees were paid on time. When I felt as if I wasn’t learning anymore after only a year in the program, I threw myself into journalistic work outside of J-school. I spent nights sleeping under a desk in my campus newspaper’s office and blowing off lectures to complete freelance assignments in order to build the skills I knew would help me get my foot in the increasingly narrow door.

It’s a path others before me have trod, like my friend Connor Garel, who graduated in 2019.

When he grew disenchanted with school, he started pitching on his own, and looked to working journalists to fill in the gaps being left by his education. In spring of 2017, with guidance from freelance journalist Harron Walker, then a senior staff writer at Vice, Garel had his first piece published in British fashion and contemporary culture magazine i-D—about LGBTQ content being censored on YouTube. Being published gave him the confidence to continue freelancing, developing contacts, and building his portfolio. If he was going to achieve his goals in journalism, he realized he would have to advocate for himself.

Until his graduation in 2019, Garel navigated uninspiring course content, regularly skipping classes and focusing, instead, on his growing freelance assignments. He would go on to publish stories in Canadian Art, Vice, BuzzFeed, Fashion magazine, Xtra, and more while still at Ryerson.

I, too, followed this route. And as I ran my mental, physical, and financial health ragged, I became increasingly vocal and critical of the school. As the number of awards I won for my work went up, so too did the number of classes I failed.

And I saw this experience represented in my peers over and over again.

I can’t claim I didn’t learn anything at university, and journalism school did help me to become a working journalist—not by teaching me, but by forcing me to rectify the gaps in my education and think critically about how I was being taught. But that’s not what I paid for. I mourn the diverse and forward-thinking J-school experience I should have had instead.

A LOOK BACKWARD: A mini history of J-schools

Does the journalism industry require education through degree programs? This question has long been debated by practitioners and those who analyze and critique the impacts of journalism. In North America, the concept of journalism education gained traction in the years following the American Civil War, as a number of groups—such as businessmen, lawyers, and journalists—sought to professionalize and establish themselves as experts in their fields. Up until this point, journalists learned reporting skills primarily on the job, in newsrooms or on city streets, often under the tutelage of senior editors. Former Confederate general Robert E. Lee was the first to introduce classes to educate journalists while president of Washington College (now Washington and Lee University) in the late 1860s, seeing them as a way to improve regional papers and rebuild Southern states. Journalism education gained legitimacy after the University of Missouri established the first professional J-school in 1908. Walter Williams, who helped found the school and acted as its first dean, said in a speech that he hoped J-schools would “do for journalism what schools of law, medicine, agriculture, engineering, and normal schools have done for these vocations.”

Around the same time, St. Louis Post-Dispatch and New York World publisher Joseph Pulitzer was developing another model aimed at providing “a sound general education” and specialized technical training, bridging the gap between liberal and practical arts. Pulitzer had been in talks to establish a journalism lectureship at Columbia University as early as 1892, but he spent the early years of the century on the fence about whether journalism schools were an appropriate method to train journalists. After years of deliberation, he committed to the creation of a journalism school at the university but only agreed to provide funding posthumously. Pulitzer passed away in 1911, and the Columbia Journalism School opened in 1912 with the help of a $2 million grant. Before his death, Pulitzer wrote that his goal for the school was to “make better journalists, who will make better newspapers, which will better serve the public.” The debate about journalism’s place in higher education continued in Canada until the end of the Second World War, when Ryerson, Western, and Carleton established their own journalism schools.

Around the same time, St. Louis Post-Dispatch and New York World publisher Joseph Pulitzer was developing another model aimed at providing “a sound general education” and specialized technical training, bridging the gap between liberal and practical arts. Pulitzer had been in talks to establish a journalism lectureship at Columbia University as early as 1892, but he spent the early years of the century on the fence about whether journalism schools were an appropriate method to train journalists. After years of deliberation, he committed to the creation of a journalism school at the university but only agreed to provide funding posthumously. Pulitzer passed away in 1911, and the Columbia Journalism School opened in 1912 with the help of a $2 million grant. Before his death, Pulitzer wrote that his goal for the school was to “make better journalists, who will make better newspapers, which will better serve the public.” The debate about journalism’s place in higher education continued in Canada until the end of the Second World War, when Ryerson, Western, and Carleton established their own journalism schools.

The terms of this debate haven’t changed much since the early 1900s, but the journalism industry has—drastically. The “golden age” of journalism in the last half of the 20th century saw large news institutions thrive on abundant resources, made possible because they had near monopolies on the cost structures associated with making and distributing physical newspapers, according to American media scholar Robert Picard. “Print media became one of the most profitable businesses in the developed world” during this time, as the mass audiences of legacy media providers attracted large advertising revenues, Picard wrote. Today, digital technology has significantly disrupted this economic model and decentralized news provision, reducing the costs of print journalism without reducing the costs of gathering and disseminating news.

Additionally, increasing public distrust, disinformation, and homogenous staff composition that fails to accurately reflect and report on its audiences are just a few of the crises that challenge journalists’ self-ascribed position as democracy’s Fourth Estate.

“This reality threatens the relevance and existence of traditional journalism education,” Picard said in his keynote address at a 2014 Ryerson University conference titled “Toward 2020: New Directions in Journalism Education.” His speech questioned professional journalists and journalism educators who “maintain that only trained journalists can speak truth to power and hold power to account,” arguing that this idealized view is “not borne out of the realities of the 21st century.” Picard equated it to “looking into a very badly distorted mirror.”

“Journalism education can only survive and succeed if it becomes much more aggressive in seeking change,” Picard told his audience. “It has to become far more innovative than it ever has been. It is not a matter of thinking outside of the box, because the box no longer exists. What is required is deciding what will replace the box or how to get along without one.”

In the increasingly unstable media landscape of 2021, Canada’s top journalism schools have done little to hold a mirror up to the industry or transform it in any meaningful way, opting to continue teaching curricula “designed to produce news factory workers who can be dropped into a slot at a journalism factory,” as Picard described seven years ago. While some progress has been made to keep up with fast-changing technologies and industry standards, current journalism students and recent graduates have come to realize the gaps in their education, and that the innovation needed to make journalism schools relevant in the 21st century is either too slow or meaningfully non-existent. “It’s not pushing boundaries at all,” says Garel. “It’s not changing the way journalism is being done. It’s not contributing to a more interesting future in journalism. It’s just training you for an industry that no longer exists, and so by the time you complete it, a lot of what you learned is already obsolete.”

The small and centralized makeup of Canadian media means that celebrated journalism schools—like Ryerson’s—serve as a direct pipeline to the industry, says Anita Li, a media consultant and instructor of Ryerson’s journalism innovation course. Li, who has taught at a number of journalism schools at universities and colleges in both Canada and the U.S., notes that many J-schools maintain strong relationships with legacy outlets like the Toronto Star, CBC, and The Globe and Mail, which often use student labour for large investigations and for-credit internships to fill in gaps left by shrinking budgets. Industry leaders are also often chosen to teach at these schools. “It’s pretty symbiotic,” says Li. “Which means it’s so important, especially in Canada, for journalism schools to stay on the cutting edge and be able to provide students with the kind of knowledge that will allow them to succeed and actually compete.”

Not only have Canada’s biggest J-schools failed to make use of their uniquely large resources to push their dwindling industry forward, marginalized students say these programs have failed to foster them at a time when their voices have never been more needed in the industry. Internal crises at Canada’s top-ranking journalism schools—the Ryerson School of Journalism, at which the [ ] Review of Journalism is based, and Carleton University’s School of Journalism and Communication in Ottawa—call for a reexamination of modern journalism education. —TYLER GRIFFIN

LISTEN TO THE STUDENTS: They want to partner to change

Heads of Canadian J-schools are aware of at least some of the deficiencies of journalism education in keeping up with an ever-evolving media landscape. In 2015, Janice Neil, then chair of Ryerson’s J-school, and Susan Harada, then head of the Carleton journalism program, along with Carleton journalism professor Mary McGuire, collected survey research and found that “many Canadian journalism programs were operating in a state of constant change, and had been doing so for at least five years prior to the 2015 survey.” Writing for Policy Options in 2017, Harada noted that journalism schools are uniquely positioned to support journalism’s core mission—“to seek the truth, to inform, to enlighten”—but only if they can provide journalism education “that is relevant and aligned with 21st century realities.” “Now more than ever, programs must infuse themselves with an innovative breed of thinkers and storytellers if they truly want to…demonstrate the value of journalism education,” she wrote. “The programs that survive and thrive will be those with the latitude to experiment and sometimes fall short, to stoke research-based expertise that focuses on new forms of journalism.”

These sentiments ring hollow for third-year Carleton journalism student Safiyah Marhnouj, who quickly felt she wasn’t getting enough out of her pricey journalism education, which almost entirely consisted of journalism theory in her first year, pushing her to learn how to write articles externally at her campus newspaper, The Charlatan. Marhnouj found her courses were being taught in the context of an outdated journalistic landscape that reflected the privileged structure of six o’clock news, while the social media skills she had grown up with were seen as unprofessional and a hindrance to storytelling, rather than an asset. “Many of my friends eventually ended up dropping out and changing programs because they were like, ‘Yeah, this isn’t for me.’”

These sentiments ring hollow for third-year Carleton journalism student Safiyah Marhnouj, who quickly felt she wasn’t getting enough out of her pricey journalism education, which almost entirely consisted of journalism theory in her first year, pushing her to learn how to write articles externally at her campus newspaper, The Charlatan. Marhnouj found her courses were being taught in the context of an outdated journalistic landscape that reflected the privileged structure of six o’clock news, while the social media skills she had grown up with were seen as unprofessional and a hindrance to storytelling, rather than an asset. “Many of my friends eventually ended up dropping out and changing programs because they were like, ‘Yeah, this isn’t for me.’”

When Marhnouj came across an email calling for proposals that envisioned what the future of journalism school could look like, she jumped on the opportunity to submit. She was invited to share her ideas at the 2019 World Journalism Education Congress in Paris as the representative for the Americas. Established 15 years prior in Toronto and held every three years, the international conference had invited students from around the world to give their thoughts on the state of journalism education, which Marhnouj says “speaks to the conversation that we’re having when we’re talking about what schools do right and wrong. A lot of times it’s just professors and faculty members getting together, and students aren’t really given a seat at the table.” At the conference, she told the room full of journalism educators and professors, plainly, they weren’t doing a good enough job teaching collaboratively with students, discussing social media and addressing the massive disruptions we see in the field today. She recalls that some laughed; others appeared shocked.

Marhnouj noticed recurring themes and sentiments in other students’ proposals, despite their studies being based in Russia, South Africa, India, and Australia. Most of them spoke about an ideal J-school that is far more open-minded in how it discusses and teaches journalism; one that makes students collaborators in their education and utilizes their extensive knowledge of digital technologies that have surrounded and informed their entire lives.

“A lot of students feel like their voices aren’t being heard in the school, in what they want to see represented in their classroom,” says Marhnouj. “Journalism’s about looking at things from a different angle, and so, a lot of students were like, ‘Let’s start looking at journalism school from a different angle. We’ve been doing this for a really long time; let’s switch things up and find a way that will be super-beneficial for students and professors, and then give us the skill sets to start making waves with storytelling.”

Connor Garel echoed a similar desire for his ideal J-school experience: “It’s about acknowledging what students’ needs and interests are and responding to that, rather than going off of what 50- and 60-year-old journalists, who are probably out of touch with what the industry is doing now, think is interesting to us,” says Garel. “At the end of the day, they’re the ones paying thousands of dollars to get an education.”

There are ways to do this right, argues Li. Younger generations are generally more compassionate, open to collaboration and attuned to emerging platforms, she says. In her classes, she invites students to challenge and debate her expertise, effectively shifting classroom dynamics to give them more ownership and autonomy over their education and passions. “We have to meet students where they are,” she says. “That’s how journalism is going to become more critical and more intelligent.” —TYLER GRIFFIN

A GLIMPSE FORWARD: What’s ahead for Ryerson’s School of Journalism

Author and Ryerson journalism professor Kamal Al-Solaylee began internally raising issues on the direction of the program regarding both his students and himself in February 2020, before the widespread impact of COVID-19. In March 2021, Al-Solaylee was announced as the school’s transformation lead in the search for a new permanent program chair, and has been tasked with creating an updated vision plan for the 21st century. He says the school previously put too much emphasis on lagging digital skills and not enough on journalism “as a way of preparing students to be responsible citizens, as opposed to content generators.”

An illustration of the school’s failure to respond to current events with timely and urgent curriculum focus, he says, was its failure to implement a fact-checking course during the four years of Donald Trump’s presidency, which he pushed for, and which didn’t materialize in that time. “I lost respect for this school the minute we decided a fact-checking course is not important enough at that cultural moment,” he says. In January, the school announced alumnus and New York Times fact-checker Rudy Lee as the school’s first verification expert-in-residence, as well as the current instructor of its fact-checking course.

An illustration of the school’s failure to respond to current events with timely and urgent curriculum focus, he says, was its failure to implement a fact-checking course during the four years of Donald Trump’s presidency, which he pushed for, and which didn’t materialize in that time. “I lost respect for this school the minute we decided a fact-checking course is not important enough at that cultural moment,” he says. In January, the school announced alumnus and New York Times fact-checker Rudy Lee as the school’s first verification expert-in-residence, as well as the current instructor of its fact-checking course.

Al-Solaylee is still working on an updated vision for the school, but says it will be one that includes “both doers and thinkers,” prepares students to think through the framing of their stories, and has a larger emphasis on long-form journalism that goes beyond the breaking news reporter model. Ideally, he adds, the vision plan will outline the urgency to bring some of the critical media research happening at the school down to the classroom level. “A good journalism school should know that it is at the forefront of huge societal changes,” he says. “Journalism school should lead that conversation on journalism, not just be a graduate factory.”

And, he adds, the Ryerson School of journalism will continue its evolution towards creating an environment where racialized and marginalized students do not have to fight for their rights to be treated equally. —TYLER GRIFFIN