How women journalists in Pakistan are fighting back—and the online spaces that are helping them do it.

Content warning: This article contains information about sexual assault and rape,

which may be triggering to survivors.

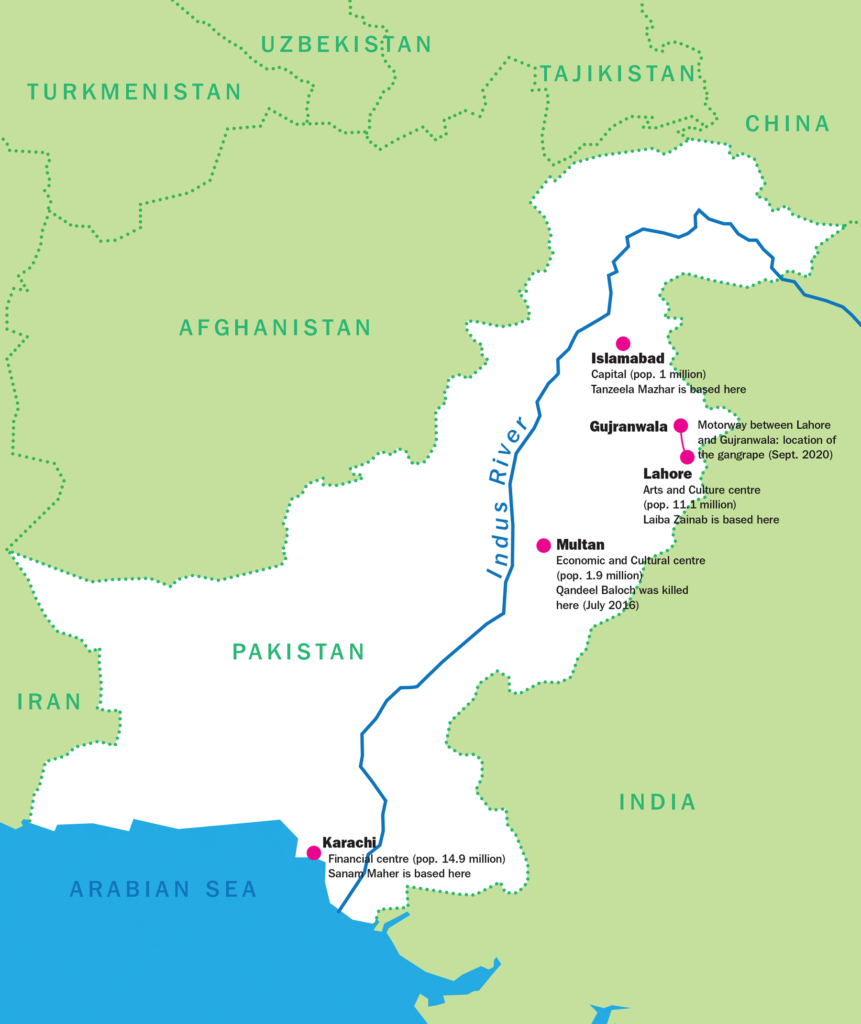

Laiba Zainab is driving in the fast lane, heading to the bank on her way back from work on a September evening in Lahore, one of Pakistan’s most populous cities and its cultural and literary hub. She’s in her sand-beige Mehran, her foot pressing down on the accelerator to make the most of the speed limit. But just ahead of her, a duo on a motorbike is thwarting her progress, and while the two see her, they refuse to move into the slow lane. Zainab honks at them, gently at first, and then with more persistence. The men on the motorbike momentarily clear out, but then slide in behind her and begin to tail her. Zainab feels unnerved; she’s conscious that she’s driving on her own and it’s been two days since a woman was gang-raped on a major Pakistani highway in front of her children. The men continue to follow her, then pull up beside her, stare at her, and laugh. It is a while before they decide to leave her alone. Zainab keeps her eyes trained on the road, her hands on the steering wheel. An unsettling feeling of despair engulfs her.

“Men go crazy when they see a woman driving,” she tells me while recounting the incident, a daily reminder of her vulnerability as a woman and a reporter in Pakistan. “They also harass you a lot, zooming their bikes in front of your car and staring at you,” she says. “They will tailgate you, or if you are standing at the traffic signal, they give very vulgar signs.”

Zainab is 24 years old and makes her living as a freelance digital journalist. She began her career as a junior reporter in 2015 at 24 News HD, a broadcast station in Multan, a small and thriving business-centred city in the southeast of Pakistan with a conservative, patriarchal culture. It’s uncommon for a woman to be a news reporter there. And Zainab not only became a broadcast reporter, but in March this year she won the best data story award in a data journalism workshop conducted by the Center for Excellence in Journalism (CEJ) at the Institute of Business Administration, one of the top universities in the country. Zainab’s story documented the many forms of additional censorship women journalists in Pakistan face in comparison to their male colleagues. That story was first published online in Urdu, Pakistan’s national language, on Sujag, a digital news organization with a mandate to highlight marginalized voices across the country.

“I have been called a false journalist, a flea market liberal, and a dirty feminist”

Daily instances of street harassment are not new to Zainab. Yet, the tailgating upset her that day because she was still reeling from the shock and fear arising from a recent event that polarized many in the country across gender lines. It also highlighted the challenge of negotiating two of her key identities: woman and journalist.

On September 9, 2020, a woman and two of her children were travelling from Lahore to Gujranwala, a smaller city just over 100 kilometres north, when their car ran out of gas. It was 1:30 a.m. and the woman phoned a relative, who urged her to call the police and set off to meet her. The driver then dialed 130, an emergency police number, only to be informed that her location—on the link road just off the highway near Gujjarpura—fell outside the highway police’s jurisdiction.

In the period between her call and the relative’s arrival, two armed men robbed her of jewelry, cash, and her ATM card. They also pulled her out of her car, took her to the fields, and gang raped her at gunpoint, with her children as witnesses.

When news of the rape broke the following morning, Umer Sheikh, a Lahore Capital City police officer and the city’s lead police investigator, under whose jurisdiction the investigation fell, made his first statement about the case, neatly laying the blame on the victim: “Now, first I am surprised that you’re a mother of three children and you left the house alone. A lone driver, you should have taken GT Road directly, where there is more population. Or at least check your fuel, you should know that there are no gas stations on this highway.”

The horrific episode hit Zainab hard. She had planned to drive home to Multan to visit her mother that weekend but cancelled her trip. The next few days were challenging and, unable to function, Zainab sought therapy. “My first instinct was fear, and it was a lot. Because it gets late at night when I leave the office. At night, sometimes I drive for recreational purposes, so I was really scared.”

Yet, she was also keen to start reporting, and turned to social media—Facebook and Twitter—for news commentary and analysis. She had just received information from a source who was a medical officer—and the child’s paternal aunt—that a five-month-old girl had been raped by her paternal uncle in Muzaffargarh, a district just south of her hometown. Zainab reported the news, but her followers did not appreciate the content of this story. “I was called a false journalist, a flea market liberal, and a dirty feminist,” she recalls. In one post, a commenter hoped that God would punish her.

Reporting on gender-based violence in Pakistan can be tricky. For one thing, there are laws in place that make it difficult for women to be treated fairly both in a court of law and in the media. In 1979 the martial law government of General Zia-ul-Haq instituted the Hudood Ordinance, a set of laws that criminalized adultery and non-marital sex, including rape. Women who were raped were seen as guilty for having engaged in illegal sex acts; thousands of rape victims were jailed as a result of these laws. Although a Women’s Protection Bill was passed in 2006 making amendments that would encourage and make it easier for women to pursue legal action against their abusers, analysts and activists felt the reforms in this bill fell short of needed revisions.

Elsewhere, in covering gender-based stories, women journalists in Pakistan face newsroom staffing challenges. Anecdotal evidence suggests that women make up a limited proportion of newsroom staff across the country, which means gendered perspectives aren’t making their way into story frames, editorial feedback, and eventually published material.

In some parts of the country the newsroom gender balance can be even more challenging. Last September 16, for instance, when politician Samar Haroon Bilour of the Awami National Party in Peshawar, in the northwest part of Pakistan, addressed journalists during a press conference on the subject of the gang rape near Gujjarpura, she condemned Sheikh’s callous remarks on the incident and highlighted the need for greater sensitivity surrounding the case: “To all our press brothers, our collective hello,” she said, “I have started the press conference with mention of this incident because in the last week so many girls from Peshawar have reached out to me and they have cried that they feel unsafe going to their education institutes and offices. We need to give them their mental peace back because they are a part of our society, and when they leave their houses they should be assured that the state is there to protect them.”

The camera pans as she speaks and her reason for greeting “press brothers” becomes clear: in a room full of journalists, there does not appear to be a single woman reporter.

The challenge of reporting on sexual assault while being subjects of harassment themselves is not lost on women reporters.

On September 16, 2020, Muna Khan, a journalism lecturer at the CEJ in Karachi, Pakistan’s largest city and its financial centre, moderated a Zoom panel on media coverage of the motorway gang rape. Khan’s guests were Mahim Maher, digital properties editor at SAMAA TV, and Tasneem Ahmar, a veteran journalist as well as the founder and director of Uks, a research centre on women in media. The trio discussed, both in English and Urdu, the ways in which narratives on violence against women in media reinforce stereotypes and cultural prejudices. Khan asked if there was anything new in how the gang rape was covered. It depends on whether you take a glass-half-full or glass-half-empty approach, responded Ahmar, pointing to positive shifts in coverage, like not naming the victim of the gang rape, while underscoring the many other problems of reportage on rape.

But, she also felt, the extent of coverage was dictated by the political fallout from the top cop’s comments. “Had the CCPO not been there, his statement not been there, probably this would have died down.”

Maher agreed and raised concerns about the insensitive approach to rape reporting in Pakistan. She recalled an incident that illustrated the problem of victim-blaming culture even inside the newsroom. In 2010, she had sent a reporter to cover a rape case reported in an elite Karachi neighbourhood. The male reporter returned to the newsroom and explained: “Ma’am, it was a dance party.”

“He had immediately dismissed it, and as a crime reporter and as a male he is obviously steeped in police culture at that time, which is, you know, dismissive,” Maher explained. “So I was really frustrated, you know, that even if she was at a dance party, it doesn’t really matter.” Maher eventually sent a woman reporter to get more nuanced information.

For over 20 years now, Ahmar has been conducting gender sensitivity training for journalists. Had the training resulted in a shift in conventions around naming victims of crime, asked Khan. “I think the training that we have conducted may have impacted some people, somewhere. Out of 1,000, I would say maybe three or four,” says Ahmar as Maher erupts into laughter and shakes her head her agreement.

Every time Ahmar trains a new batch of media practitioners, she says, she has to deal with new mindsets and toxic philosophies all over again. Still, things are changing and she feels some of it is a result of activism on digital platforms. “Social media is playing a big role, because women, especially, have found a voice to vent their rage and be heard,” says Ahmar. “If the mainstream media is not focusing on them or they don’t have access, they have social media.”

Zainab, who was attending the panel session, shared her thoughts via chat. Why is the onus on women to explain to their male colleagues what type of language they need to use while covering such cases like the motorway gang rape, she asked. Who should participate in conversations about improving reportage on sexual assault?

After the panel, Khan received many emails from attendees requesting her to invite male journalists to the discussion as well. Khan agreed. With men far outnumbering women in the newsroom and making decisions about language, framing, and tone, including them in conversations makes sense. For now, panel discussions like this one help create a safe space for considerations about reportage and new approaches. “Online spaces have provided an opportunity for women to carve a space for themselves and it is allowing them to speak in a voice that is their own,” says Khan.

Indeed, organizations like Digital Rights Foundation (DRF) often host discussions that have implications for women journalists. A particular area of emphasis is the right to free expression for women and addressing online hate. The organization’s mandate is to educate the public and promote policy changes for digital governance. In 2019, the organization published a report, “Female Journalists in New Media: Experiences, Challenges and a Gendered Approach,” which looks at the impact of online harassment for women journalists like Zainab. In the absence of more mainstream coverage and focus beyond political news coverage like the Lahori cop’s victim-blaming statement, these organizations come together to provide critical space to unpack the socio-cultural underpinnings that influence reportage on sexual assault.

When news about incidents like the motorway gang rape break out, women journalists have a dilemma. As journalists, they are bound by their public service mission to spread information and analysis. As women and often as subjects of harassment themselves, they are shocked at the incident and the remorseless victim blaming. Knowing that there is a job that needs to be done and with many holding within themselves memories of the workplace harassment they have suffered, reporting on gender-based violence involves a complicated internal dialogue. They navigate through traditional electronic and innovative digital media, raising important questions about who speaks and how for women in media.

Online harassment is deeply personal for many journalists in Pakistan, especially women. On August 12, 2020, a joint statement condemning online harassment faced by women in the media was published. The 165 signatories include renowned journalists in Pakistan like Ahmar, Munizae Jahangir, and Asma Shirazi. Zainab was also a signatory. Organizations like the Network of Women Journalists for Digital Rights as well as the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan were also on the list. The statement called upon the current ruling political party, Tehreek-e-Insaf, to put an end to the alleged coordinated attacks by government officials and their followers online. Attacks, the statement reads, lead to self-censorship and therefore have a direct impact on journalists’ ability to fulfill their professional duties. “Our social media timelines are then barraged with gender-based slurs, threats of sexual and physical violence,” it states. “These have the potential to incite violence and lead to hate crimes, putting our physical safety at risk.”

A New York-based non-profit, the Coalition of Women in Journalism, launched an online campaign on September 14, 2020, to support the statement. The hashtag #ThreatstoWIJ appeared on Twitter, and many women came forward with testimonials about the harassment they experienced as journalists in Pakistan, as well as in Iran and Afghanistan. One of them was Tanzeela Mazhar, a senior anchor and co-founder of the Women in Media Alliance, a platform for women journalists to discuss their work and collaborate. WIMA is another example of the type of organization that is bringing women journalists together to amplify their voices and take collective action, and it was also a signatory on the statement.

Victim blaming isn’t restricted to the cases of sexual harassment on which journalists report. Inside the newsroom, too, women face gender-based discrimination and harassment. In January 2017, Mazhar went public with her disappointment around the results of a newsroom complaint she had filed in 2009. She tweeted: “In an inquiry on my complaint of harassment against masood shorish, PTV committee asked y didn’t you leave job if u were harrassed?” The inquiry Mazhar was referring to was conducted after she initiated a harassment complaint against Shorish, then director of current affairs at Pakistan Television Corporation (PTV), which is the state-owned television broadcaster of Pakistan. Mazhar alleged that in 2009 Shorish made “unwelcome advances.” Upon posting the inquiry committee’s response, Mazhar started a discussion on Twitter about why harassment is not seen as a serious crime in Pakistan and why people were not ready to talk about it.

She says that there was much support from the public. “When I shared it on Twitter and brought the discourse to social media, I got huge support. Many women activists, bloggers, vloggers, and journalists, they were standing by me and supporting me online, where we could make the politicians realize, and they drafted a resolution for my case and took it to the parliament.” Still, Mazhar resigned a month after the inquiry committee dismissed her complaint.

She feels just being an opinionated woman appears to be a problem in Pakistan. “Our society is trying to stop women. If you are harassed in public, you are told that there is no need to go out in public to begin with.” And while the response online is also toxic, with people hurling abuse if you happen to challenge society’s norms, there is a distinction. “In online spaces we have one benefit—that there is less threat, less risk,” says Mazhar. “In online spaces you have a space to express yourself, you can battle with the comments and the responses, but at least your space is yours and you are allowed to say what you want to say.”

Social moral codes and public judgment pose a challenge for women reporters in Pakistan, complicating their ability to report on women’s issues. When she was interviewing Arif Alvi, the current president of Pakistan, Mazhar came away with the impression that viewers focused less on the content of the interview than on her appearance: why wasn’t she wearing a dupatta, many asked, referring to the loosely draped scarf commonly adopted by many women. When she supported Meesha Shafi, a Lahore-based actor and singer, for speaking out against her alleged abuser, actor and singer Ali Zafar, she recalls that people responded by questioning her own “un-Islamic” dress. Mazhar wears her hair short, just above her shoulders, and for some viewers such a choice seemed to be the problem. And not surprisingly, her support for others who are also stigmatized for defying taboos and customs receives the same treatment. When, for instance, in 2016, she tried to organize a protest outside the press club after the honour killing of social media star Qandeel Baloch, she recalls that her friends questioned her wanting to organize support for a “dubious character.”

In many ways, Qandeel Baloch’s story is instructive. Born Fouzia Azeem in the district of Dera Ghazi Khan, in the southeast part of Pakistan’s Punjab province, Baloch was a polarizing figure, dividing the public and journalists along the lines of what is appropriate exposure for women online. Using Facebook and Instagram, she posted personal videos and pictures that challenged gender norms in the Islamic republic. For some, her photos were too risqué and inappropriate. For others, videos of her seductively wishing her viewers goodnight were pure entertainment. Still others saw her claiming the space as a win for women’s freedom. But for her brother, Qandeel’s growing celebrity was an affront to the family’s honour. So, when she was visiting her family in July 2016, he strangled her. The murder resulted in a temporary reckoning in the media and all across Pakistan.

Covering Baloch’s killing resulted in a specific kind of challenge. Zainab understands this well since she hails from Multan, which is close to Dera Ghazi Khan. Culturally, the two locations are not dissimilar.

“Online spaces have provided opportunity for women to carve a space for themselves, allowing them to speak in a voice that is their own”

She has many stories about hurdles in the way of doing complex but important stories. Some time ago, while attempting a story on fake blasphemy cases in Multan, Zainab once reached out to a local lawyer, asking him for details of the ongoing court cases. Pakistan’s blasphemy law has its roots in colonial British India and was introduced in 1860; Pakistan inherited this law when it was born in 1947. But under the military dictatorship of Zia-ul-Haq, who sought to Islamicize Pakistan, a series of new clauses were introduced, with severe penalties, including death or life imprisonment for those who disrespect Islam. In practice, those laws are often misused to target religious minorities like Christians or Ahmadi Muslims. Sometimes mere allegations can cause religious extremists to take matters into their own hands and punish the accused themselves. When Zainab sought answers, she recalls that the lawyer did not respond to her questions but asked instead whether she was prepared for the violence she might face if he gave her the information she was looking for. She didn’t follow up.

At the time of the Baloch murder, Zainab had already resigned from 24 News HD following multiple experiences of harassment from her male colleagues—like the time one came and sat in her car and pinched her cheeks. Before Zainab could respond to the unwelcome touch, he did it again, leaving her frozen on the spot, seething. Such incidents pushed Zainab to resign, but a friend who still worked there shared disturbing ways in which the team responded to its coverage of Baloch’s murder.

The atmosphere in newsrooms across Pakistan was charged. Many men seemed to deal with Baloch’s death with insensitivity, while women reporters appeared to be devastated by the news. Baloch was symbolic of a precious and often inaccessible freedom; her murder cemented its intangibility. This newsroom polarization was captured by journalist and author Sanam Maher in her book A Woman Like Her: The Short Life of Qandeel Baloch. In it Maher narrates how rookie Adil Nizami was the first reporter to reach the scene. He scrambled for a shot of Baloch’s dead body, assuming that the decision whether to blur out her face would be his boss’s. Nizami was relentless in his quest for the picture. Maher writes in her book: “I need to see for myself, Adil thought as he quickly slid open one of the ambulance windows. His hand, holding his mobile phone, snaked inside. He stared at the puffy, blue-lipped face for a split second. He began filming.” In that moment, a police officer grabbed Adil’s arm and told him to have some respect for the dead, recounts Maher in her book. “But Adil had got his shot.”

The image Nizami took was later shared countless times, all over social media, and its digital imprint still remains.

While Nizami could get away with the audacious disrespect of the slain Baloch, Maher had to tread carefully at every step while reporting for her book. For the first time in her career, she hired a local reporter, a man, to be more secure as she moved around in Multan. The local journalist arranged a meeting with other journalists in the area at the back of a store. Maher was the only woman in the room and she asked her fellow reporters many questions about on-ground realities since the murder.

She recalls one male reporter expressing resentment at her presence as a woman from the city. For safety reasons, she didn’t live in a hotel. Despite wanting to for her work, she didn’t even stay overnight in Baloch’s village and drove back and forth from a friend’s home in the city for reporting.

When she heard about Baloch’s death, Maher, like Zainab, recalls feeling an unprecedented depth of sadness. Even before her death, women feared for Baloch’s safety. She was tackling codified practices and challenging the reputation of clerics, a brave effort in a land of patriarchal hypocrisies. On one occasion she exposed the cleric Abdul Qavi. On one hand, Qavi was a God-fearing cleric, on the other, he was an enthusiastic selfie taker who held a “friendly meeting” with Baloch under the guise of “guiding her” toward the righteous path. She uploaded the video and it became viral. Hundreds rushed to defend Qavi, and the online abuse directed at Baloch mushroomed. In the days leading to her murder, death threats spewed out at Baloch like everyday greetings. When she uploaded her video response on social media, she said, “You’re going to miss me when I’m gone….Will you be happy when I die? When I die, there will never be another Qandeel Baloch.”

Reporting on gender-based violence is tricky. Pakistan laws make it difficult for women to be treated fairly in court and in media

No social media celebrity had achieved the kind of popularity that Baloch did prior to her death in 2016. But her murder has inspired women’s groups into action and online spaces became increasingly organized. Around the same time, Mazhar created a WhatsApp group of women journalists. When the participant limit—over 250 people—was reached, she made another group, quickly realizing the need for a formal organization for women. While men in the newsroom take the time out to sit together and discuss politics and culture, women journalists rarely do. Even when there are scholarships available, those opportunities often go to men, while women are discouraged from attending training and workshops, says Mazhar. Evidence of a lack of access and presence at the table is everyone. Of the top three brass at the Pakistan Federal Union of Journalists, for instance, all are men.

In this climate, Zainab also found a breathing space online to report on stories that are brushed aside in traditional newsrooms by working, until recently, at the digital operation Sujag. With a sharp focus on labour and women’s rights, Zainab worked mostly alongside women in a house-turned-newsroom space. And in December 2020, she made the decision to go freelance and take on a digital marketing job to supplement her income.

Collaborations among journalists and other groups have also grown, and their interdisciplinary nature enhances the scope and scale of representative journalism. Lawyers, activists, and journalists come together as women to produce alternative narratives with a focus on lived experiences and a reliance of journalists as storytellers, says Shmyla Khan, a lawyer and the research and policy director at the Digital Rights Foundation. Khan also recently published an e-zine called Feminists Movement Go Online to make online space for women and non-binary people. The e-zine invites writers to employ a variety of forms, including video essays. In the zine’s October 2020 issue, for instance, Zainab produced a video essay to cover Aurat March, an annual country-wide demonstration on Women’s Day that has polarized both journalists and the general public since it became an annual event in 2018. Zainab’s video on the march focused on its success in Multan. Her coverage provided an alternative to the often misogynistic questions mainstream journalists ask each year.

DRF also supports women journalists in sourcing evidence. An online mapping of gender-based violence is a case in point. The online tracker collects reported incidents of gender-based violence reported in English-language newspapers. Khan says the findings show that incidents that are high profile, like the motorway gang rape, are widely reported but tend to focus on sensational details such as the Lahore cop’s comments in this case; an assessment or critique of overall coverage rarely takes place. Such reports provide essential quantitative data to support conversations like those conducted by the CEJ.

Sometimes the challenge in covering sexual assault, harassment, or misogyny comes from within the ranks. When she tried to critically cover Baloch’s murder case, Mazhar says she received a text from a seemingly progressive actor, who was incredulous that she would bother with the story. Some of her women friends also said it was wrong to fight for justice for Baloch because she didn’t deserve it. It was also a woman who questioned Mazhar when she tried to hold a protest against her killing.

These women may be regular citizens, but sometimes they also occupy key positions in journalism. Fiza Akbr Khan, a broadcast show host for Bol News, a Karachi-based media company, is a case in point. When women took to the streets to demand justice after the motorway gang rape, she hosted a known misogynist producer, Khalil-ur-Rehman, on her show. In the segment available on YouTube, Khan agrees with Rehman’s patriarchal understanding of how Pakistan’s honour rests in the body of a woman. Criticizing a popular yet contentious slogan from the march, “Mera jism, meri marzi” (My body, my choice), the two lambast women for exercising their right to free speech.

With each video, Khan’s show runs “Pakistan’s #1 Anchorperson” as a caption on the screen. As the host of an Urdu-language channel, Khan’s reach is far greater in a country where language barriers and internet literacy limit the reach of the online medium. With such voices that echo historic, state-endorsed, and patriarchal views on women and honour, even online spaces become contested ones.

Zainab recalls when a senior woman journalist from Multan once passed an unpleasant remark about her, to which a senior male journalist in the Multan newsroom responded that Zainab was a talented reporter and always got the job done. Such feedback, even though it is rare, gives Zainab the fuel to carry on.

“I cannot leave my passion, and I cannot disappoint myself,” she says. She also is driven to serve her audience: “I cannot disappoint those who take inspiration from me.”