What’s so funny about a woman drawing cartoons?

David. Michael. Theo. Patrick. Greg. These are the names of the cartoonists I usually see as I flip through the Toronto Star, The Globe and Mail, Montreal’s The Gazette, and the Winnipeg Free Press.

There’s more than one version of an illustrated former Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, often the punchline of pointed policy humour. In one cartoon, he’s dressed as a jolly Santa Claus, cheerfully handing out gifts while homeowners quip, “Is that my wallet?”

In another, a Cheeto-coloured U.S. President Donald Trump and a sharply cheekboned tech billionaire Elon Musk stand side by side. The punchline isn’t in their features, but their shadows. Behind them, ominous silhouettes hint at power dynamics. Trump, shrunken like a puppet, dangles from strings pulled by Musk. The joke is intimidating and alarming, the caricatures grotesque and bold.

One day, in the Globe, I noticed a simple cartoon with no contorted body parts. It depicts a relatable moment with everyday folk discussing alcohol sold in convenience stores. It’s grounded, subtle, and more refreshing than typical political caricatures. I glance at the credit beneath the drawing: Gabrielle Drolet. A woman? Yes, this cartoon was drawn by a woman. For a moment, I’m struck. Is this a fluke? A rare outlier in a male-dominated field? Maybe so.

Women in Canadian editorial cartooning have long been scarce. Sue Dewar, who cartoons for the Toronto Sun and serves as the secretary for the Association of Canadian Cartoonists, can only think of about five women who regularly contribute editorial cartoons to Canadian news organizations. Dewar says she was the only one with a full-time newspaper job—also at the Sun—until she retired in 2017.

Most don’t receive any recognition. Since 1949, when the National Newspaper Awards were established, no woman has won for editorial cartooning. In 2021, Canada Post named five men—Brian Gable, Serge Chapleau, Terry Mosher, Duncan Macpherson, and Bruce MacKinnon—as Canada’s greatest editorial cartoonists, commemorating them with stamps for “thought-provoking” and “seminal” cartoons shaping Canadian identity. No woman made the cut.

The industry’s gatekeeping is reflected in Dewar’s early career. When she first started, over 40 years ago, she took her portfolio to the Star, where editors told her she was too “left wing.” The reception at her next destination, the Globe, was worse. There, she overheard editors behind a partition jokingly saying, “We don’t want any women in here.” Eventually, Sun cartoonist Andy Donato suggested Dewar use a masculine-sounding alias. It worked. An editor approved her cartoon.

Women like Dewar no longer have to work under pseudonyms, but cartooning is still defined by barriers that make it difficult to thrive. Job insecurity, harassment, and scarcity of fellow women continue to hinder their creative freedom and professional growth. As an industry, it’s time we sharpen our pencils and ask ourselves: what’s so funny about a woman drawing cartoons?

Doodles and Dreams

Like many young artists, Drolet started as a doodler and a dreamer. As a five-year-old, she loved drawing animals and birds. When her mom asked what she wanted for Christmas, her wish list included Backyard Birds by Robert Bateman, a Toronto painter well known for his colourful wildlife scenes. She sat at the kitchen table, studying the birds’ shapes and lines, trying to recreate them.

Many years later, after much practice, which included drawing daily as part of her covid-19 lockdown routine, Drolet had a cartoon published in the New Yorker’s Shouts and Murmurs section. Titled “Your Twenties as Video-Game Achievements,” the piece had a Super Mario Bros 8-bit style, featuring an avatar wearing a graduation cap with a caption that read: “Level up! You completed your B.A.!! Now you can work as a barista, a P.R. person, or an underpaid freelancer.”

Drolet continued contributing to the New Yorker on a freelance basis. She drew about everyday themes, like life during the pandemic, and eventually illustrated her way into CBC and The Coast, a Halifax newspaper. Then, in 2023, when veteran cartoonist Brian Gable retired after 35 years at the Globe, she secured a spot in the paper’s weekly rotation. David Parkins, an editorial cartoonist, handled cartoons from Monday to Friday, while Drolet, Graham Roumieu, and Michael de Adder took turns drawing the Saturday spot. Globe opinion editor Natasha Hassan says she took a chance on Drolet on a freelance basis, mainly because Drolet was an illustrator more than a seasoned editorial cartoonist. “I was trying to find something that might shake it up.”

At age 27, Drolet is one of the few women who have contributed editorial cartoons to the Globe. Recently, turning her wit to the U.S. election, she drew a humorous take on the Biden administration’s fizzling campaign. Her cartoon featured a roundtable discussion between former U.S. President Joe Biden, then–Vice President Kamala Harris, and other politicians looking at a chart outlining campaign strategies aimed at pandering. Among the suggestions were attending a Kansas City Chiefs game or Taylor Swift’s Eras Tour. After the one-year trial, however, the Globe retained de Adder as Parkins’s backup cartoonist. “He’s a natural,” Hassan says of de Adder. “It wasn’t so much ‘no’ to Gabrielle; it was more ‘yes’ to Michael. He was a real catch.”

Today, Drolet occasionally writes and creates illustrations for the Globe’s opinion section. In a December 2024 essay, she shared her love for crossword puzzles and creating personal holiday traditions. She depicted a Christmas tree inside a crossword puzzle, with a rendering of herself standing next to it, holding a pen. Drolet also contributes essays and artwork to publications such as The Narwhal and Chatelaine. “I’m lucky not to rely on publishing cartoons for my entire income,” she says, making a living from her print shop and freelance work as a journalist. “I’m able to make cartoons I care about and love.”

For a while, Drolet kept her rejections to herself but, over time, she changed her mind. Now she posts rejected cartoons on social media, letting them live beyond the inboxes of editors. “You have to put yourself out there,” she says. “It’s a really important way to engage with audiences and editors.” One of the rejections was a twist on Dr. Seuss’s Oh, the Places You’ll Go!, and captured the experience of pandemic-era graduates who would be stepping out into an uncertain job market. The New Yorker had passed on it but after she posted it on her Twitter account, it racked up almost 600 likes. In March 2025, the National Newspaper Awards announced Drolet had been nominated for her editorial cartooning in the Globe.

Law and Caricature

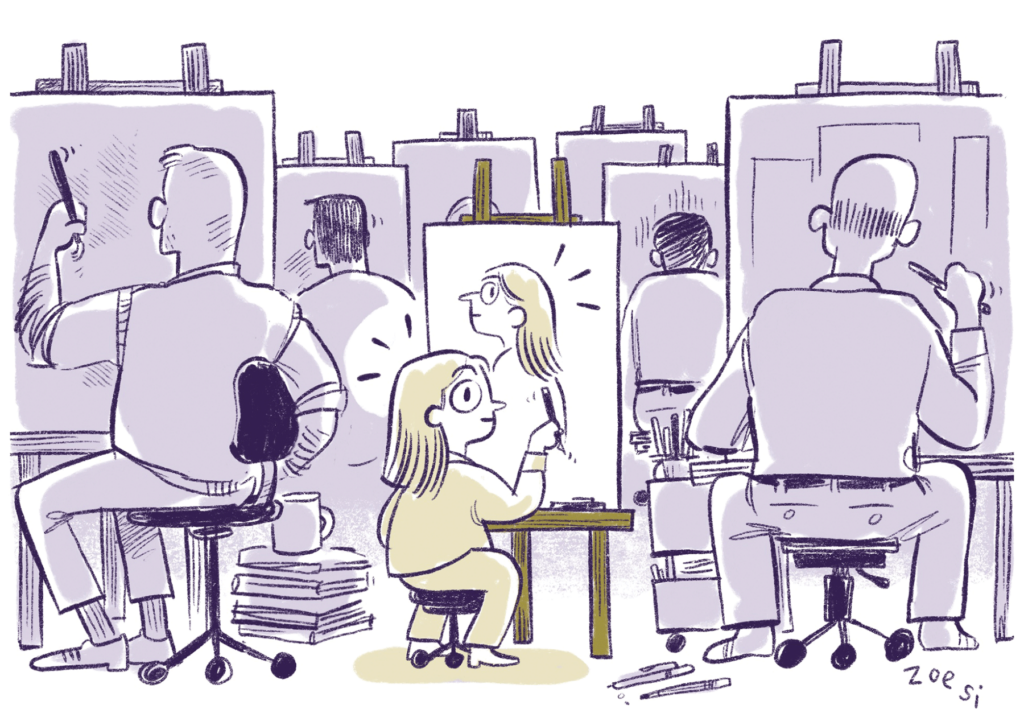

Zoe Si, an ex-lawyer, believes in taking risks with cartoons. She used to spend her days practicing family and divorce law in the public sector, serving people experiencing barriers to accessing the legal system. It was a constant stream of paperwork, drafting, reviewing, and editing often harrowing legal documents. When the emotional weight drained her, she drew comics about her daily grind. She began posting the works on Instagram, and her following grew. She fed her feed with cartoons that capture relatable struggles, like her ode to the nipple bra, which critiqued fashion trends that create unrealistic expectations for women. Si’s Instagram platform now has 101,000 followers.

“We don’t just need to draw politicians. Honestly, who cares? What matters is who they impact”

Zoe Si

When Si sold her first cartoon to the New Yorker in 2019, she took it as an opportunity to leave her legal career. “I don’t think I have the emotional constitution for that kind of work,” she says. The stress had become overwhelming, and, ultimately, it wasn’t sustainable. In 2020, HarperCollins offered her a three-book illustration deal. “It was enough to justify quitting my job for a year.”

Si submitted cartoons to the Globe, but struggled to get them placed. Her cartoons weren’t welcomed, she thought, because they weren’t traditional caricatures, and didn’t poke politicians directly. She was determined to draw the human experience, not to fixate needlessly on politicians’ foibles. “I will absolutely not be drawing Trudeau for your amusement,” she says. If Canadian publications had room for her vision, she’d pitch them but, instead, she’s found success pitching editorial cartoons to American publications including the New Yorker, a more established place for cartoonists. “We don’t just need to be drawing politicians. Honestly, who cares?” she says. “What matters more is who they impact.”

But Si’s Instagram posts that showcase her cartoons do resonate in the motherland. On March 1, 2024, she posted two women bundled up in winter outerwear, one gazing down at her toes hidden beneath bulky boots. The caption read, “You wouldn’t know it, but I’m manifesting spring with a seasonal pedicure.” Her Canadian followers quickly approved in the comment section, sharing winter woes while fantasizing about warmer days.

Alone in Abuse

Both Drolet and Si have cultivated supportive audiences through social media, a necessary route for women in media without staff positions. Sometimes this openness is preyed upon by those facilitating gendered harassment. On the morning of May 31, 2024, while walking to the Canadian Association of Journalists conference from her hotel, Drolet’s phone lit up with notifications. Days after the Globe published her cartoon—a drawing of graduates at convocation, their caps forming the colours of the Palestinian flag—she was flooded with “the most horrific and hateful emails” from critics opposed to pro-Palestinian student protests. The outrage was amplified when HonestReporting Canada, a self-described watchdog against “anti-Israel” bias in news media, wrote about her cartoon, prompting the organization’s followers to attack her online. “I got called a ‘bitch’ a lot,” she says. She says her editors would probably have been helpful, but as a freelancer, she chose not to ask. Instead, she relied on industry peers at the event for support.

The International Center for Journalists (ICFJ) has found that nearly three in four women journalists experience online violence—but only one in four report it to their employers. Nearly half of participants report being harassed with unwanted private messages. Most women cartoonists are freelance, meaning they, like Drolet, lack the protection that comes with being on staff at news organizations. CBC has corporate policies to protect employees’ personal security and encourage civil discourse. The Globe has community guidelines that prohibit personal attacks against journalists and racism, sexism, and other forms of discrimination. To be freelance, however, is often to be alone, and that means navigating harassment without the support of colleagues. “There was no one,” Drolet says. “If I had a staff position, I could have gone to someone and said, ‘Hey, this is happening, and it’s frightening and bizarre. I don’t know how to respond to it.’ Instead, it was just me, staring at my phone, thinking, What am I supposed to do about this?”

The ICFJ report, published in 2022, also found that participants reaching out for help often receive no response from their bosses. When they do, it’s often dismissive advice, like “grow a thicker skin” or “toughen up.” Two percent of respondents said they were asked what they had done to provoke the attack. “People would rather assume that a woman is stupid, rather than making a joke,” Drolet says. “I’ve posted things that are clearly meant to be funny, and people respond with, ‘Well, you don’t understand what’s happening here.’”

Gender communication scholar Cheris Kramarae’s muted group theory, which outlines the behavioural norms women are often required to fit in to be heard by men, aligns with this. Her theory reflects the real-world argument that men, particularly those who lean into crude or derogatory humour, are widely accepted because society expects it from them. The sharp jab, the cutting punchline, the ability to speak without consequence—these have long been associated with masculinity. Women, by contrast, face entirely different expectations.

So long as traditional gender dynamics persist, openings for new voices, especially women’s voices, remain few. Some male cartoonists, such as de Adder and the New Zealand Herald’s Rod Emmerson, stress that women’s perspectives are needed in editorial cartooning. In fact, there’s a strong, supportive culture among cartoonists, according to Dewar, Drolet, and Si. Dewar reminisces about “Ring Night,” a tradition where cartoonists gathered for a dinner party and awarded each other “skull rings” to represent the editors they survived. “Women,” Emmerson says, “bring a completely different viewpoint to the profession.”

When cartoonists lack diverse representation, it inevitably shapes the stories and characters that make it to the page. A 2014 statistical analysis of New Yorker cartoons found that, out of 1,810 characters featured, approximately 71 percent were male and 95 percent were white. Women cartoonists, it also said, are significantly more likely to draw women characters. On average, women cartoonists drew about 47 percent women characters, compared to 27 percent by male cartoonists. Although the New Yorker is not a newspaper, the study shows that women’s involvement produces more diverse content.

Research from the Journal of Comparative Research in Anthropology and Sociology says that women have concerns shaped from gendered experiences. And without women’s point of view, these perspectives and interests are less effectively represented. “Women understand women better than men do,” says Irina Zamfirache, the author of the study. “We should not draw the conclusion that this is a men’s world and women do not have a place of their own.”

Women’s Perspective

Dawn Mockler, a lifelong New Brunswicker, balances her physiotherapist career with cartooning. Many are featured on CartoonStock, an online database for licensing cartoons, products, and original art. She says cartoon imagery drawn by men tends to include guns, blood, and violence, and often fails to cover issues such as women’s safety and reproductive rights. “It’s not part of their lives,” Mockler says. “It’s cool if you have somebody with that different viewpoint.” Emmerson agrees, and acknowledges that reproductive rights, motherhood, and rearing children are topics with political overtones that call for women’s perspectives. “It’s a difficult subject for me,” he says.

One of Mockler’s cartoons, published in the U.K.-based bimonthly The New Cartoonist in 2022, plays on gender dynamics in the workplace. It shows a woman sitting among men at a meeting, when one of the men proudly says, “Well, we wanted to make our first female employee feel comfortable, so we put some menstrual products by the water cooler.” The men in the cartoon think the gesture reveals grand thoughtfulness. It is however making the woman mortified, evident by her flushed cheeks. Mockler says, “How can someone take that seriously coming from a man?”

Without a woman’s perspective, cartoons about women can miss the mark. In 2019, de Adder apologized for the way he drew Jody Wilson-Raybould, who was justice minister at the time, and Justin Trudeau in a boxing ring. Trudeau is advised to “keep beating her up, solicitor-client privilege has tied her hands.” Some felt the drawing of Wilson-Raybould tied and gagged was insensitive towards not only violence against women, but Indigenous women, in particular. Drolet says that while some men cover women’s concerns with sensitivity and nuance, “Having more cartoonists from a wider array of backgrounds means having a more diverse pool of cartoons, with a more diverse set of viewpoints.”

Drawing the Short Straw

In a precarious business, the future of women producing editorial cartoons is uncertain. “We’re in a media landscape,” Drolet says, “where not many publications have a cartoon legacy.” De Adder says editorial cartooning in Canada has been in decline since the 1980s. While many professions have become more diverse over the decades, newspapers have largely stopped hiring new editorial cartoonists altogether. Since de Adder was hired by the Halifax Daily News, and cartoonist Graeme MacKay was hired by The Hamilton Spectator, there have been no new full-time, permanent hires—male or female—by newspapers with the resources to support them. Older cartoonists like de Adder are the last ones standing. On rare occasions when a publication does provide contribution opportunities, de Adder says they tend to choose someone with a proven track record rather than taking a chance on unknown talent. “Once people get their job,” Emmerson says, “they put up steel barriers.”

As the editor in charge of the Globe’s editorial cartoons, Hassan thinks about whether cheeky satire has a place in journalism outlets at all during a time when misinformation and disinformation run rampant. As part of her work, she works closely with the cartoonist to satirize fairly. “Can you even play around with the facts?” she wonders, signalling the possibility of further limitations on the form due to the current political climate. Regardless, politics dominate the editorial page. “I don’t see editorial cartoons moving into the ‘the way we live’ sort of vibe—at least not for now.”

This means women cartoonists such as Drolet and Si, whose work veers outside political commentary, will likely weave careers via paths that do not include mainstream papers. Si is focused on her graphic memoir, while Drolet is on her way to publishing her book debut, Look Ma, No Hands: A Chronic Pain Memoir. They’re still finding ways to showcase their work, even if it’s not in the editorial cartoon section alongside the Davids, Michaels, Theos, Patricks and Gregs. “You do the work, put it out there, and hope it lands somewhere,” says Si. “I feel like I snuck into a back door.”

side bar:

Editorial Pencil

Content—including cartoons—is influenced by newspaper ownership and where the funding comes from.“I can’t do what I want to do anymore,” Sue Dewar says. Because the Ottawa Sun is owned by Postmedia, which is owned by Chatham Asset Management LLC, an American hedge fund—“friends with Trump,” she says—cartoons she’s submitted in recent years that lampooned right-leaning figures such as Danielle Smith, Pierre Poilievre, and Donald Trump were rejected by her editor. She recalls another time when she drew a cartoon about General Motors, only to have her editor reject it, explaining that the company was their only advertiser.

Today, cartoons are often about staying “on brand,” as Dewar puts it, but that wasn’t always the case. Back in 1873, John W. Bengough, one of Canada’s first celebrated cartoonists, wielded that power with his satirical magazine Grip, and wasn’t afraid to go after the country’s leaders. According to the Canadian Encyclopedia, his sharp commentary, particularly during the Pacific Scandal, exposed the corrupt dealings between private interests and the Conservative Party, which funneled money to cover election costs and influence a national rail contract.

From that moment on, no prime minister was immune to the hand of political cartoonists. Sir Wilfrid Laurier faced the pen of Henri Julien in the early twentieth century, and Pierre Trudeau couldn’t escape from Jean-Pierre Girerd’s humour in the 1970s and ’80s. Politicians knew they had to answer to the people—but also to the sharp critiques of the country’s cartoonists. “Political cartoonists are the canary in the coal mine,” Rod Emmerson says. “When they’re all chirping in unison about Trump, you know something’s wrong.”

Opportunities have always been limited, but they became even more scarce when newspapers like the Sun were sold to Postmedia. At a cartoon convention, Dewar spoke with Pulitzer Prize–winning cartoonists from McClatchy papers (also owned by Chatham Asset Management), who had been let go after the change in ownership. Postmedia’s acquisition of SaltWire Network Inc., the Atlantic Canada newspaper chain, led to the fall firings of about 60 employees, including de Adder.

The trend of political cartoonists losing their jobs isn’t restricted to Canada. Emmerson says U.S. political cartoonists face similar challenges, notably under ownership that capitulate to Trump. For example, Ann Telnaes, an ex-Washington Post editorial cartoonist, announced her resignation from the publication on January 3, 2025. Nick Anderson, formerly an editorial cartoonist at the Houston Chronicle, was permanently laid off six months after Trump was elected in 2016. “There is a climate of fear in American newsrooms,” Anderson says. Many outlets, like CBS, seemingly settle lawsuits they could win just to avoid conflict with the president. Corporations that own media have other financial interests beyond media holdings that make them more reluctant to protect freedom of speech because other corporate interests are. – Alexia Baggetta

About the author

Alexia is in her final year of the Master of Journalism program. She interned with CBC Podcasts and graduated from the MIT program at Western University. Her work has been published in the Toronto Star, and currently works in a creative marketing role. When she’s not writing or working, she loves baking, crafting and spending time with her boxer.