Pandemic measures in South Africa are impacting press freedoms and revealing a threatening relationship between the police and the press

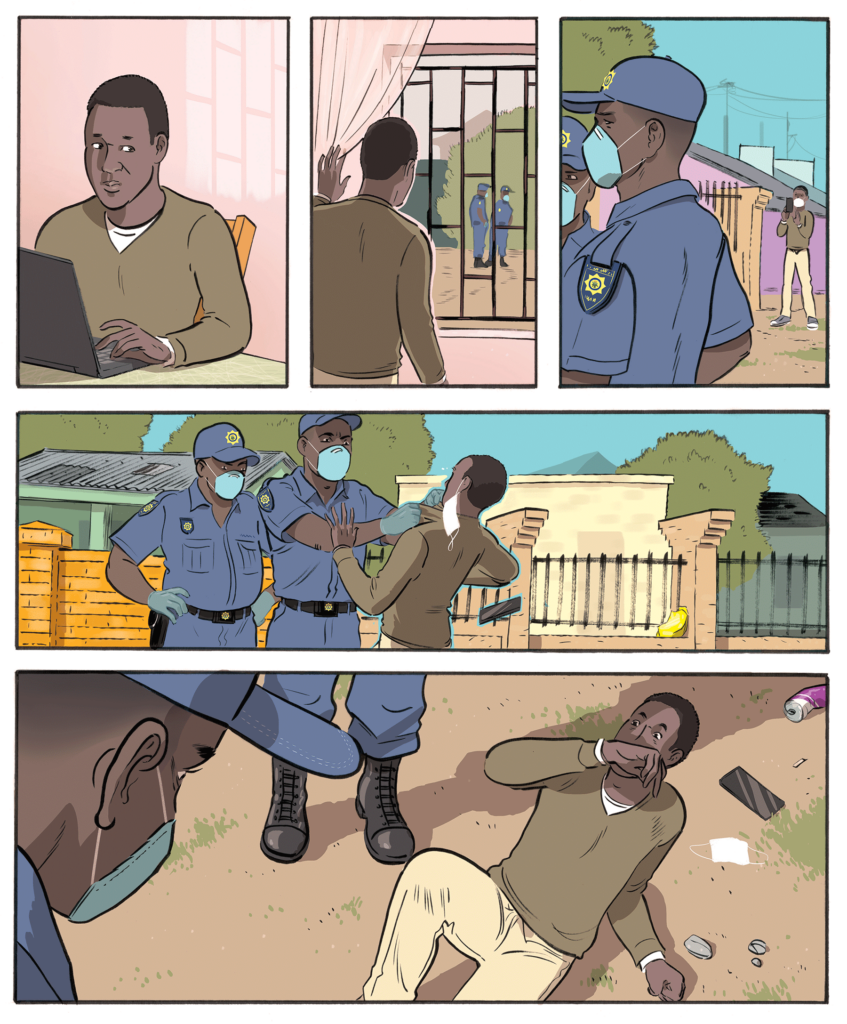

Paul Nthoba was in his neighbourhood in Meqheleng, on the western coast of South Africa on May 15, 2020, when he was attacked. The owner and editor of the now-defunct weekly paper, Mohokare News, had observed police officers out on a patrol during a state-imposed COVID lockdown. Nthoba, whose readers were asking for evidence of police presence in neighbourhoods, stepped out to capture the patrol on camera. “I was going to go introduce myself and talk to them,” he tells me, thinking back on that moment. “But the way they were standing, I saw that as a perfect [photo], because they were unaware that I was coming and I thought it could be a good shot. Let me take a picture and then I’ll go [talk to them].”

Nthoba had just taken a photograph when the officers turned on him. “[They asked me], ‘Why are you taking our photo?’” He explained that he was a journalist. Instead of respecting his right to do his job, a senior officer told the others to “go and pick him up.” Then, Nthoba says, the officers began to assault him. He recalls asking over and over again what he had done wrong, but got no answers. Finally, the officers let him go. He went straight to the police station and laid a charge of assault. There, a senior officer told him it was wrong for him to take a photograph. In the meantime, the officers who had attacked him returned to the station. When they saw Nthoba there, they assaulted him again. Then they arrested him for violating COVID-19 lockdown regulations, though Nthoba says he followed all of the protocols at the station. Not long after, on June 29, 2020, journalist Mweli Masilela was shot in the cheek by police, who were firing bullets at protestors, while covering a story at KaNyamazane Township near Mbombela.

In March, Azarrah Karrim had a similar experience. An investigative journalist with News24, a South African online news publication, Karrim was out in the field reporting on COVID-19. She was aware of the use of force and other problematic tactics employed by the police. So when news of the lockdown and an imposed curfew was released, she took to the streets to see how police would deal with members of the public. Even with her experience and knowledge, she didn’t expect the police to start shooting at her. “We had a hard lockdown and I went out and, you know, journalists are considered essential workers,” says Karrim. “So, I had my press card and my permit, and then I went to Yeoville. It’s quite a decrepit neighbourhood, it’s quite dangerous. And I went out there to see if people are following the lockdown rules. Like, Yeoville is normally bustling. But I went there and it was dead quiet. So, it was quite a sight.”

While she was there, Karrim says the police chased her and shot at her. She kept shouting out that she was a journalist, an essential worker. “It’s something I’m still trying to get over today because I was screaming at them to stop shooting at me,” she says. “I was just standing there, there was no one there, and then the [police] just hunted me down with shotguns with rubber bullets. Shooting at me as I was running away.”

There has been an increase in the reported incidents of police force against journalists in South Africa in recent times. The country is ranked 32nd on the 2021 World Press Freedom Index. It isn’t seen as a place with an endangered press, especially given its location in southern Africa, surrounded by countries that rate very high on the risk meter for journalists. Despite its brutal history and the long-standing impact of apartheid, the country’s new constitution defends press freedoms and the public’s right to know. Journalists don’t end up dead in South Africa and there appears to be a thriving press in the country.

A little digging into areas of press freedom concerns shows that there are limitations on those freedoms, prime among them the often unchecked power of law enforcement officers. Legally and constitutionally, South Africa has press freedoms. Yet, in the two-year period since the onset of COVID-related restrictions, it appears that police brutality, limited media ownership, access to information challenges, and several other issues combine to reflect a less-than-rosy picture of press freedoms in South Africa. It’s a discussion that should be on the table regardless of the country’s ratings.

It’s difficult to look at press freedom issues in South Africa without considering the country’s apartheid history. During this era, which lasted close to half a century, between 1948 and 1994, the white-minority-led National Party ruled over the country and institutionalized and legalized racial segregation, which it enforced through a series of violent practices. To control information shared with its citizens, the state employed strong censorship measures. Though there were publications and news outlets that openly criticized the apartheid system and its government, they were still hampered by various amounts of government censorship. In particular, a set of harsh laws prevented journalists from reporting on activists and anti-apartheid rallies—anything that was considered a “banned person or organization.” An example of this was when the government banned Nelson Mandela and the African National Congress, and made it illegal to “quote or publish photos” of them. Journalists who reported during those times recall how challenging this made their work. Vic Alhadeff, former chief subeditor for the Cape Times, recalled, in a journal article, the challenge was “to inform readers as what was happening and to speak out against apartheid—without breaking the law.”

Furthermore, the South African government wanted to control the way that people, especially English speakers, viewed the apartheid regime. Newspapers that published in Afrikaans were generally proapartheid, while newspapers that published in English were normally antiapartheid. In an attempt to control the narrative and further control journalists, the government tried buying its own media outlets—one overseas and one in South Africa, called The Citizen—that were proapartheid. However, the information ministry’s attempts to control the narrative were exposed during the 1977 Muldergate scandal, after journalists at the Rand Daily Mail uncovered the government’s role in pushing out propaganda through its own vehicle in an effort to dilute the stain of its apartheid reputation globally.

Despite the apartheid regime’s censorship laws, the South African government still respected the right of white South African journalists to report, or “the rule of law for whites.” In a 2018 journal article titled “Journalism During South Africa’s Apartheid Regime,” it says that under this law, the system “respected what was said in parliament and what was said in court; i.e., speech in both forums was regarded as privileged and could therefore be freely reported.” This allowed antiapartheid newspapers to report on the system—on activists, rallies, protests, and politicians—so long as it was in court and so long as the journalists were white. Nonwhite journalists, like many other racialized people in the country at the time, faced “tight media control and restrictions on civil liberties, such as public protests; and a despotic system for so-called non-whites, who were effectively regarded as units of labour, utilised—and exploited—by whites; whose family’s lives were routinely destroyed; who were classified as second-, third- or fourth-class people.”

What this meant was that during this period, the police had extraordinary powers. Assisted by the military, they used violent tactics to keep the country’s nonwhite population under control. Protests were met with brutal opposition. People were whipped and beaten with sjamboks, a heavy leather whip commonly used by the South African police during apartheid. Others were shot, tortured, and killed, and in two heightened periods of control, in 1985 and 1988, the government declared states of emergency. The first gave President Pieter Willem Botha unlimited power to rule by decree, enforce curfew, and restrict and censor news about the political unrest. This was the first time his government targeted only the political groups and activists fighting against the apartheid regime. The second time the emergency applied to the entire nation in order to silence the growing unrest.

Though apartheid ended in 1994, reports of police brutality remain common in South Africa. In fact, the South African Police Service (SAPS) is considered one of the most violent policing systems in the democratic world. It is also unusually antagonistic toward its citizens. Part of this is because the system itself did not change, leaving the institution as a remnant of the apartheid infrastructure. The early postapartheid-period efforts to improve the SAPS with training, community building, and better recruitment processes have little effect today. Corruption and politics reinforced the SAPS as a tool for those in power. According to the Independent Police Investigative Directorate, “[m]ore than 42,000 criminal complaints were made against the police between 2012 and 2019, including rape, killings, and torture.”

The South African Police Service (SAPS) is considered one of the most violent policing systems in the democratic world

When COVID-19 reached South Africa in 2020, the South African government issued a nationwide level-five lockdown. Citizens weren’t allowed to leave their homes except for grocery shopping or to access essential services. This included essential municipal services, which included those provided by newspapers, broadcasting, and telecommunication infrastructure—that is, journalism and reporting.

The experiences journalists faced while covering COVID raised policing concerns to a new level. Karrim, Nthoba, and Masilela had each reported or written about their experiences, making it difficult to ignore the pattern of abuse. Because of the volume of COVID infections and their severity, the South African government declared “a state of disaster in line with the disaster management act.” The National State of Disaster, which expired on March 15, 2022, is a set of regulations to stop the spread of COVID-19 throughout the country.

The act has been criticized for giving government authorities (such as the police) unrestricted power over South African citizens. In particular, the government criminalized the act of putting out misinformation about COVID-19 or the government’s response to the pandemic. This includes fining or imprisoning (or both) anyone who is caught writing and sharing misinformation. The new regulations “have the potential to dim that light, opening up the possibility of abuse and limitations on vital information and facts,” wrote Angela Quintal, the Africa program coordinator at the New York-based Committee to Protect Journalists, referencing real gains in press freedom that had been made over the years.

If you ask South African journalists what their top press freedom concern is, many are likely to respond with: the police. Their professional experiences reflect the problem. Personally, too, such interactions have an impact. Karrim, for instance, says she experiences “a sense of panic” every time she leaves her house. “We’re journalists. We can’t be told what we can and can’t report, and we can’t be shot at,” she says. “Our police in South Africa have a history of violence. Since apartheid, there’s been senseless killings of citizens…and it seems like they don’t know their own rules and regulations on what they can do and can’t do to citizens.”

On the day that she was shot at, two other journalists were also assaulted or prevented from doing their work. The South African National Editors’ Forum issued a press release noting that Athi Mtongana, a reporter with Newzroom Afrika, had been “shoved and assaulted” by an official from the Cape Town Law Enforcement Department while covering a story of refugees being moved from a location in the city. In February, a police officer had also employed force in preventing Jan Gerber, a parliamentary reporter, from recording an incident when an opposition member was blocked from entering the parliament ahead of the budget speech.

Nthoba, who was assaulted for taking a photograph, is still trying to seek justice through the courts. He recently shut down his publication because he could no longer afford to run it. The financial challenge of doing journalism remains a global problem, with South African newsrooms having downsized, journalists being let go, or entire departments being shut down. Despite the financial reality, one area of concern for Nthoba is the failure to deliver news and coverage to all audiences. “We don’t have publications that are owned by the people from all sectors of society. Because we are a multiracial society. And we have different needs for news,” he says. “We have a majority of unemployed people who want to be fed news on opportunities, and what they can do….As much as we have a diverse media in our country, but it is not able to cover many issues that need to be covered.”

The challenge of the extent of coverage and meeting audience needs is connected to media ownership, says Quintal. “Because what you have is media owners who see owning either broadcast media or newspapers might give them enough class for their other businesses to succeed.” She’s referring, in particular, to the case of the Independent Media, owned by Iqbal Survé, who “leads a media that will, in fact, cozy up to government, so that, in fact, his own business interests will benefit.” There are others, too, she says, who “want newspaper titles, for example, to make money; they would rely on government funding, government advertising. And so, they would put editors under pressure to toe the line because if they don’t, then they’re not going to get government advertising.”

Since the South African government is a big advertiser, many publications know that “if you want government advertising, lo and behold, you’ve got to ensure that you don’t show the government in a poor light.” There are several cases, Quintal says, where journalists have been fired for pushing too hard for editorial independence. One example is when Phathiswa Magopeni, the former South African Broadcasting Corporation editor-in-chief, was fired for refusing to give into political pressure; she was asked to interview President Cyril Ramaphosa’s wife in order to improve his image during his presidential campaign. Such realities naturally also impact public confidence and trust in the media. “We do have a lot of protests in our country, and violent protests,” says Nthoba. ”You’ll find that journalists are sometimes becoming the victims of people’s anger.” According to the Global Disinformation Index, 41 percent of South Africans are suspicious and mistrustful of media outlets.

As in many places, including Canada, because of the devastating effects of the financial reality on local newsrooms and media concentration in major urban areas, there are significant zones of news poverty. “We don’t have visible media in the rural areas,” says Nthoba. “But at least now we have [access] to the internet and online social media.” Still, data can be expensive and inaccessible in some parts of the country. According to a 2021 study conducted by Cable.co.uk, South Africa ranks 136th in the world for its mobile data pricing. In South Africa, it costs an average of $3.33, which is R 38.93, for 1 GB of data. Minimum wage in South Africa, in 2021, was R 21.69 an hour and the average cost of bread was R 14.30. For the average citizen in South Africa, this means that accessing data is prohibitive. Moreover, communities that live outside the borders of the metropolitan areas cannot access the internet easily. This limits the news that is available to them, especially as many news outlets move toward a digital platform.

Yet another concern is access to information for journalists to pursue some of the more complex and layered stories. In 2011, the African National Congress, the country’s leading party, established a Media Appeals Tribunal. The tribunal concluded that freedom of the press is not an absolute right. Instead, it must be weighed against an individual’s right to privacy and human dignity. A journalist could not report on everything, the tribunal rules, and the public did not need to know everything that politicians did. An uproar followed, with many calling the Tribunal’s decision unconstitutional. The 1996 constitution states that “Every person has the right of access to all information held by the state or any of its organs in any sphere of government in so far as that information is required for the exercise or protection of any of their rights.”

A journalist could not report on everything, the tribunal rules, and the public did not need to know everything that politicians did

“There exists a sort of standoffish relationship between the media and most government departments,” explains Kyle Cowan, an investigative journalist with News24. “I think some of the communications policies are very Cold War era. Protect the state at all costs kind of thing. And we saw that a lot during COVID-19.” Cowan and his News24 colleagues pushed for more data from the government and found access difficult, finding many deficiencies in the data gathering process. “Even today, we have one government institution that’s reporting the higher number of COVID-19 deaths than the actual National Department of Health is reporting.”

Sometimes months pass without any communication or response from government offices, says Karrim, and a big concern for her is dealing with control over what can and should be reported. Not long ago, she was on a walk with the minister of police in an informal settlement in Johannesburg to observe how COVID-19 regulations were being followed. A few community members gathered and began chanting to get the minister’s attention. While Karrim was recording the scene, the minister’s media spokesperson came up to her and covered the camera with her hand. “You can’t record that,” she told Karrim. “‘We don’t condone this,’ she said. ‘You’re with us. You’re on our side.’ And that happened to me once.”

Government interference is not new to South African journalists. Because of how frequently they cover political and police corruption, they often find themselves being pressured and threatened by various parties and politicians for “sweetheart” or flattering coverage. In an article published in The Sowetan, Songezo Zibi, the former senior associate editor at the Financial Mail, said: “There are political forces that are out to destroy journalism and will do everything possible to undermine its credibility, even where there is no reason to do so. It is important for journalists to recognise these people and political formations for what they are: antidemocratic forces that seek to create permanent confusion so that ordinary people, the true owners of democratic systems, can no longer make informed political choices that sustain our system of self-government.”

In 2018, the South African National Editors’ Forum lodged a complaint in the Equality Court against the Economic Freedom Fighters for making a series of threats against South African journalists. Women journalists who reported on the EFF were called derogatory names and supporters of the political party sent online threats demanding the journalists be sexually assaulted and killed. This brought to the fore the growth in online attacks—verbal assaults, death threats—toward journalists, especially journalists who are racialized women. “The online harassment, the cyberbullying that journalists do come under, particularly female journalists,” says Quintal. “It’s particularly bad in South Africa….There is certainly concern that social media is being weaponized against journalists.”

The level of online abuse toward journalists, especially women journalists, takes an emotional toll on them. “One of my [co-workers is] constantly questioning whether she’s in danger,” says Karrim. “And that’s something I’m sort of grappling with now. So, to be a journalist not only are you dealing with access to information, but also dealing with that backlash. And constantly being like, ‘Is this worth it? Should I die for this?’”

While the digital era comes with its slew of problems, there is no denying that it has given journalists access to audiences previously out of their reach. The internet also allows journalists certain freedoms when it comes to reporting on stories in newsletters, online magazines, online newspapers, podcasts, videos, et cetera. In particular, WhatsApp has been especially useful in providing news to people in politically turbulent countries. In South Africa, many journalists and observers agree that the environment is not as turbulent. “If viewers or journalists are arrested and then accused of false news or prosecuted, you know, there’s a chance that the Constitutional Court may, in fact, rule that it’s unconstitutional,” says Quintal. “The same cannot be said about other countries in the region, who then look to South Africa and use South Africa as an example as to, ‘Well, if South Africa can do it, why can’t we?’” This is true, agrees Karrim. “I think that, theoretically, press freedom is held to a very high esteem in our constitution. I think our press code provides safeguards for us and our sources.” Cowan also feels that relatively speaking, “media freedom” is not much of a South Africa issue.

South Africa is, after all, a free country in a largely unfree neighbourhood. With its relatively high rank on the World Press Freedom Index, many neighbouring countries look to South Africa as an example. However, press rankings alone do not present the full picture. Since they focus on extreme acts of violence and repression, they don’t capture the significance of the loss of the public record or the inability to get at and/or tell complex stories about powerful places and people. These challenges elevate concerns of press freedom issues in the South African context, providing more resonance for the concerns shared by Karrim, Nthoba, and others.

“In South Africa, press freedom means writing without fear. We are an equal society, in all spheres of life, in every sector of our life,” says Nthoba. “[But] we do not have enough media voices, alternative media voices, especially from people who were excluded in the past, to operate in that space and to own that space.”