Is its focus on food the iconic magazine’s recipe for survival?

I’m on my way to meet a friend when I decide to stop at an Indigo to pick up the latest issue of Chatelaine. Gazing at the rows of other women’s service magazines, I can’t spot it. Strange, I think. How could the biggest bookstore chain in Canada not carry one of the country’s most iconic magazines?

Ten minutes of playing I Spy later, I find it shelved among the food magazines like Bon Appétit and the Allrecipes “Soups and Stews” issue. The placement isn’t surprising given that the only coverline is “Holiday Cookie Hall of Fame,” and the cover features a sea of…holiday cookies. For the past 10 years, the 96-year-old magazine, whose distinctive covers hardly ever featured anything but a woman for decades, has devoted just 13 of 82 covers to these women since 2012. Almost all the rest were a smorgasbord of pies, pastas, salads and more.

Marjorie Harris, a Chatelaine editorial staff member in the 1970s, imagines Doris Anderson’s take on today’s food focus, mimicking her signature gravelly voice: “Darling, this is such crap!”

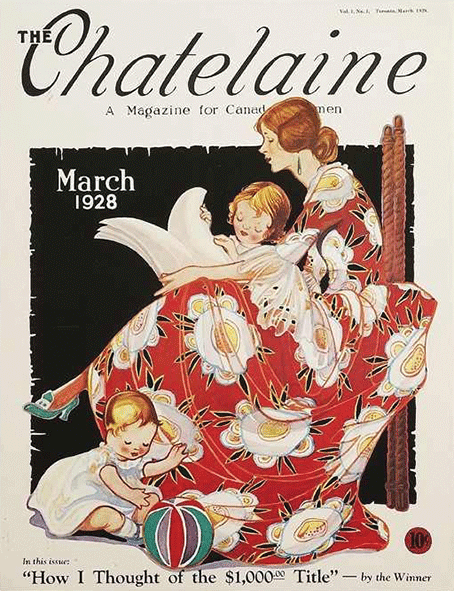

Doris Anderson wasn’t Chatelaine’s first editor. That was Anne Elizabeth Wilson, who wrote in her 1928 inaugural column that the magazine would cover “the multifarious and ever-growing questions which are uppermost in the minds of women in the Dominion today.”

In reality, when The Chatelaine began in the late 1920s, it primarily carried light features, a lot of mostly mediocre short fiction, plus lifestyle departments such as “The Promise of Beauty,” a makeup and beauty section, and “The Domestic Workshop,” “which seeks out and investigates for the housekeeper new equipment of Canadian manufacture.” But woven in were a few articles about social issues pertinent to women. Early editions included features on topics like the high mortality rate of mothers in rural Canada, whether women should earn wages outside of marriage and “Checking the Divorce Menace” about Canada’s new divorce act. Political articles were also sprinkled in, like “Are Women Wanted in Public Life? And the Important Question Is Are They Really Needed?” (The author’s answer was yes.) December 1929 carried “Now That Women Are Persons, What’s Ahead?” by Emily Murphy, one of the five women involved in the famous Persons Case decision, which found that women were eligible to sit in the Senate.

Wilson’s tenure was brief: Byrne Hope Sanders took over in September 1929 and, except for a break to do wartime volunteer work, would occupy the editor’s chair until 1951. During those years, Chatelaine (it dropped The in 1931) would continue to include a dash of social and political content juxtaposed with more typical articles. In January 1933, Agnes MacPhail, the first woman elected to the House of Commons, contributed “If I Were Prime Minister”; “The Domestic Servant Problem” ran in the same issue. In his book The Monthly Epic: A History of Canadian Magazines, Fraser Sutherland notes that “The Depression itself invaded the genteel pages” of magazines at the time. April 1933 contained the feature “I Am a Canadian Mother,” in which the anonymous writer described the privations of life on relief: “My children are starving and cold.” The same issue had a story that asked, “Can You Live Up to Your Spring Hat?”

During the war years, the conflict was regularly reflected in Chatelaine’s pages. Departments ran features like “Will War Affect Our Fashions?” and “Can You Keep Your Job After the War?” Chatelaine also began a department called “Home Front,” which featured war-themed articles about “facts and forecasts concerning the changing picture of wartime living” and “Meals on Shift,” which offered advice “for everyone coping with a topsy-turvy routine.” Readers were encouraged to knit “woolen comforts” for “the courageous women” in England’s services.

Postwar saw a sharp increase in articles about motherhood: “A Note to Brides: Don’t Delay Parenthood,” “It’s Fun Raising a Family.” There was also a renewed focus on marriage: “Four Crises in Marriage,” “Why Husbands and Wives Nag” and pieces like “He Loves Me…He Loves Me Not,” a list of beauty dos and don’ts “to treasure his ideal of you and cultivate a fresh new beauty through the years.”

After Sanders left in 1951, Lotta Dempsey was editor for just eight months, followed by John Clare, the magazine’s only male editor. Doris McCubbin joined the staff in 1951 in the advertising department. By 1957, she was top of the masthead and would stay there for 20 years.

Initially, her Chatelaine was much as before: mostly traditional women’s magazine content, heavy on fashion, beauty, food, and romantic fiction, with a few features that addressed social issues and politics. The same year she took over the magazine, she married David Anderson, a lawyer, facing pressure from her husband and Maclean-Hunter to give up her career once she was a wife and mother. Yet, as Anderson wrote in her autobiography Rebel Daughter, what she wanted “more than anything to be able to look after myself and make sure every other woman in the world could do the same.”

A few years into her tenure, Anderson began to introduce controversial topics: in August 1959 “Should Canada change its abortion law?” argued that illegal abortions were endangering lives, making Chatelaine one of the first major publications to cover the topic. “The Pill Nobody Talks About” addressed the release of the game-changing birth control pill.

It wasn’t just through features that Anderson created what academic Valerie Korinek calls a “‘closet’ feminist magazine.” There were also her hard-hitting editorials, which she initiated in 1959. As Korinek says, “One cannot underscore how atypical Anderson’s plain spoken, often sardonically blunt, comments were for a woman’s magazine.” In her editorials, Anderson often took a position on current social issues, such as the lack of women in the political and public spheres, like “The House of Commons—Exclusive Male Club?” (“As a Canadian woman I am ashamed to have to admit to women of other countries that we only have one woman member in our House of Commons to every fifty-two men”) and “Case of the CBC’s Missing Women” (“Isn’t it time we became accustomed to seeing our own sex in some other role than as infrequent adornments on our national broadcasting network?”).

Over the years, she would write about such major issues as the need for day care, unequal pay, and gender violence and discrimination (“In the movies, rape is just routine”). She once explained that “I find the editorial, the personalized editorial form, a very useful device for covering sharp, controversial issues very quickly, and I would hate to give it up. I cannot see that I’m going to give it up. I can’t see that I’m going to run out of topics, or that the country is going to have all its problems so beautifully solved that I am going to have nothing to say.” For Anderson, a typical broadside might look like her August 1967 editorial called “The Snail-like Battle for Progress,” in which she lamented the slow fight for women’s rights: “Apparently nothing happens in this democracy until everyone is in favor of it.”

Yet, despite her thorny commentary, Anderson’s magazine still published conventional lifestyle content like fashion, beauty, and food. “I think her intention was not to scare up a public that she respected and not to frighten them off,” says Harris. Anderson also generally put models on the cover, which staff complained about. “It sells copies,” Anderson would growl. As Susan Crean reports in The Monthly Epic, “End of the monthly debate.”

But tucked in among the stories like “Fabulous Fakes,” about how to buy the right plastic flowers, and “Hair: From Plain to Smashing in 15 Minutes,” there were always the features such as “How Our Divorce Law Degrades Us” and “Why Women Are Still Angry Over Abortion.” “She wanted to draw in a whole new generation of much more politically aware women,” says Harris.

“The Last Word Is Yours,” the lively back-of-the-book letters-to-the-editor section that Anderson had introduced in 1958, was proof that she was succeeding in reaching that audience. The section served as a kind of community forum for readers, whose letters discussed and sometimes challenged the views of the editors and writers, even other readers.

Anderson had a lot of leeway with the content because the men in charge of advertising often did not read any of it. As she wrote, “[T]hey had little interest in what Chatelaine was trying to do for its readers.” These stories that the Maclean-Hunter men were not reading were developed in Anderson’s weekly editorial meetings. Every week, the senior editors would pile into her office and seat themselves around her big desk. The meetings would start with a piece of gossip—had Pierre Trudeau had a facelift?—or a discussion of some current event, like the release of statistics about the rate of abortions. Then, while she called on her editors to report what they were working on, she would open a drawer in her desk and get out her nail polish and file. “Well, whad’ya got?” she would drawl, starting to paint her nails scarlet.

“I can’t remember any place I ever worked where it was intellectually as exciting as it was in those years,” says Harris. In 2007, the late Erna Paris wrote of “Doris’s unfailing expectation that the articles that appeared in her magazine would be well-researched and strong, but always fair.” Many of the progressive articles assigned to writers who eventually became the who’s who of journalism: June Callwood, Michele Landsberg, Barbara Frum….Still, according to Anderson, she had to coax writers into working for Chatelaine because many preferred bylines in Maclean’s, the Maclean-Hunter flagship.

After about an hour, Anderson would signal the end of each story meeting: “Outta here. Off you go.”

The magazine wasn’t perfect. Not only did almost every cover feature a slender, white model, stories about women of colour or diversity issues were scarce. There was also problematic content by today’s standards regarding diet and weight. A November 1972 article, “Beautiful Losers,” was about a “Fat Farm.”

There was also the Mrs. Chatelaine contest, which launched in 1960 (it became Ms. Chatelaine in 1973). Open to “all homemakers living in Canada,” it asked entrants for essay-style answers on everything from “their house-cleaning regimes” to “their philosophies of child-raising and homemaking.” According to Anderson, the contest was an effort “to balance the strong feminist line” she was taking with the magazine, arguing that “the contest kept us more closely in touch with our readers than anything else we ever did” However, Korinek notes that “[t]he contest epitomizes the material for which women’s magazines have been repeatedly criticized by writers and scholars, ranging from Betty Friedan to Susan Faludi.”

According to Korinek, the magazine demonstrated attempts at diversity for the time period, pointing to examples like the November 1968 issue that contained a six-article special section on “Canadian Indians 1968,” whose cover featured Haida filmmaker Barbara Wilson; and the January 1969 cover story on Adrienne Clarkson, then a popular TV host. As she says, “I think we’ll always look back and think, Oh, well, why weren’t we more aware of racial diversity? Why weren’t we more aware of class diversity? Why weren’t we more aware of religious diversity? Why weren’t we more aware of sexual minority communities? But we also have to put that in the context of the era.”

By the late ’60s, according to Fraser, one in three women in Canada read the magazine, making it the biggest and most profitable title in the company, surpassing Maclean’s. But despite Anderson’s success, she wasn’t immune to the salary inequity she often highlighted in her editorials. At that same time, she later wrote, she was making $23,000 compared to the $53,000 that Maclean’s editor Charles Templeton was earning. When she sought the editorship of Maclean’s in 1969, it went to Peter Gzowski, which left Anderson “infuriated by the abominable way [she] had been treated,” she writes in Rebel Daughter. Later, in 1977, she was passed over for the position of publisher of Chatelaine, which also went to a man—the first female publisher, Lee Simpson, wasn’t named until 1988. Soon after, Anderson resigned after conflict with Bruce Drane, the man who had got the publisher position, and feeling she “had stayed too long” at the magazine.

At the time of her death in 2007 Anderson was perhaps the highest-profile feminist in the country. After leaving Chatelaine, she served as president of the Canadian Advisory Council on the Status of Women between 1979 and 1981, then the president of the National Action Committee on the Status of Women from 1982 until 1984. “I had always been a revolutionary and a feminist, but something of a closet one, working under the decorous cover of Chatelaine. Now I had been forced to cross that invisible line between being a respected, and even powerful, woman of the establishment and being perceived as a true rebel,” Anderson recalled in her autobiography. She was published widely, and even wrote several novels. When she died at age 85, the myriad tributes included a whole issue of the journal Canadian Woman Studies. In Chatelaine itself, she was lauded as “the mother of us all.”

Would this mother describe the current magazine “such crap,” as Marjorie Harris suggests? I think she’d be kinder and more understanding.

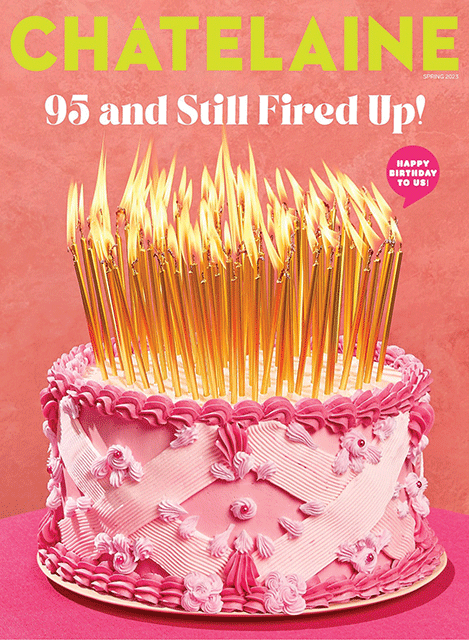

True, today Chatelaine’s frequency and print circulation are much diminished: four times a year and roughly 70,000, down from 12 times a year and an average of 530,000 a decade ago. But it’s survived while almost all other Canadian English-language women’s magazines have not: titles such as Homemakers, Elm Street, City Woman, and More have come and gone. Only its long-time competitor, Canadian Living, is still publishing. The overall climate for Canadian magazines has always been tough, and more recently it’s been characterized by sharply declining subscription and newsstand sales as readers turn to online content and plummeting ad revenues due to digital competition. The 80th anniversary issue was more than 50 percent ads; last year’s 95th one was 15 percent.

True, there hasn’t been a cover featuring a photo of a woman since April 2021, but tucked inside the 94-page Fall 2023 issue—a respectable size these days—along with a lot of food and lifestyle editorial, were pieces like “Islamophobia in Canada,” and a profile of Toronto mayor Olivia Chow. And last year, the magazine won gold for best service and lifestyle magazine at the National Magazine Awards.

Maureen Halushak, Chatelaine’s ninth editor since Anderson left, has held the job since 2019. One of the changes she’s overseen is the 2022 decision that upped the amount of food editorial. As she noted in her editor’s letter then, readers would “notice even more food content in this issue, and in every issue going forward.” In the Winter 2023–2024 book that translated to 42 editorial pages out of a total of 78. Halushak says the team made the decision because readers are passionate about food and because it’s an area of interest for advertisers. She notes that it’s also strong evergreen content that performs well both digitally and in print. “There’s Food and Drink, which is a little bit more elevated than Chatelaine. There’s Canadian Living, which definitely has excellent recipes, but is perhaps not as visually compelling. We really wanted to create a unique identity around food for Chatelaine that was really bold and bright and contemporary. And we didn’t see a lot of that in the current Canadian market.” The irony here is that Canadian Living, the magazine’s old rival (it touts itself as the “#1 lifestyle brand for women”), currently has nearly double Chatelaine’s circulation and frequency.

According to Eithne McCredie, a circulation consultant for numerous Canadian magazines and the publisher of the Literary Review of Canada, the move was a smart one because niche magazines are easier to sell than more general-interest titles. “Chatelaine is putting an emphasis on food, but not necessarily going all food,” pointing out that all-food titles like Ricardo and Taste of Living have folded.

Another change is that the magazine is purposely skewing older. Robert Fulford, writing in Toronto Life, once reported that after a $2 million redesign in 1999, the magazine gained more readers in the 24–35 age demographic. “Many young Canadian women never opened Chatelaine and were likely to describe it as ‘my mother’s magazine,’” he said. Today, one of the readers is my mom, and the 2024 media kit says, “Chatelaine celebrates, inspires, informs and empowers an often-overlooked demographic: women aged 35+.” These days, the average print reader is 45 and the average digital reader is 41. The content reflects this. In the Fall 2023 issue, for instance, the magazine published an eight-page spread called “We Need to Talk about Menopause,” which addressed the most common menopause fears and debunked hormone-replacement therapy myths. And the Spring 2024 issue contained an article by Rona Maynard, who was editor of the magazine between 1994 and 2004, about urinary incontinence. She says she never would have published in such a piece in her time or would have buried it deep in the editorial because she wouldn’t want the magazine to write about “60-year-olds peeing their pants.”

Erica Lenti, the deputy editor, features, says they try to mix topics in their online and print content because that’s what readers want. “Like our readers love to make easy weeknight recipes, but they also want to read about Islamophobia. They also want to read about menopause,” she says. “They want to know about what’s happening in the world and about health issues that are affecting them, and about the big topics that affect their everyday life.”

Those topics are often addressed by BIPOC writers. In September 2020, in the wake of the murder of George Floyd, Halushak announced in her editor’s letter that henceforth 40 percent of the magazine’s budget for freelance content would go to racialized writers. Lenti says this practice is still ongoing. Recent examples include website features like Supriya Dwivedi’s “Why Canadian Politics Is Still Unsafe for Female Politicians,” about the online hate frequently directed women MPs; and Saira Peesker’s “Meet the Moms Pushing for a New Approach to Canada’s Opioid Crisis.”

Last year, Ayesha Habib, a Chatelaine editorial fellow, suggested the magazine begin keeping track of the balance between negative stories that are trauma-based and more positive ones, which Lenti says they have been doing ever since. According to Lenti, the team considers a variety of things when creating the story mix: who is telling those stories, the timeliness across print issues and online, the identities and experiences of the sources and stories, and the tone of the stories, to name a few. “All those considerations are still on the table, like ensuring we’re not just telling traumatic stories about marginalized communities, making sure that there are still a good mix of happy and joyful stories,” she says.

A number of those pieces appear online only, including in two popular subscription newsletters, “The Dish” (“Our very best stories, recipes, style and shopping tips, horoscopes”), which is delivered several times a week, and “In the Kitchen” (more food, once a week). Halushak says these have an open rate of about 50 percent, higher than the industry average. According to the 2024 Chatelaine media kit, “The Dish” newsletter has over 85,000 subscribers. All this content is produced by a staff of seven and a half, including the people responsible for the art side. A decade and a half ago, for the 80th anniversary issue, photos of the 46-member team—including Halushak herself, then an associate editor—ran across the bottom of a spread.

According to Halushak now, the magazine is experimenting with other types of content like online taste tests and coverage of pantry food products. A recent example of the latter is the “Canada’s Best Hot Chocolate Mix: A Definitive Ranking” piece posted online in mid-January. They’re also planning to start offering special events this year. Halushak is upbeat about the future: “I really think that the media industry has always been super-challenging, so I remain optimistic. And my goal is just to eventually hand over a really vibrant brand. Editors of Chatelaine have been talking to Canadian women for the past 95 years. And I just want to keep that conversation going.”

Not all readers are happy with the conversation. On Chatelaine’s Instagram post about the Winter 2023–2024 issue, one user commented, “I…notice there’s quite a bit of advertising disguised as editorial in the new issue. Given that it’s down from 12 issues to 4 a year, I wonder if Chatelaine will live to see its 100th year. Sad.” Another reader was more positive, writing on a post marking the magazine’s 95th anniversary: “Yay Chatelaine! Continuing through the generations.” My mom’s take is, “It’s one of the little pleasures of life. They offer a little escape from the everyday while learning new things.”

Though the magazine’s food emphasis and reduced editorial content are quite different from what Anderson’s Chatelaine offered, the magazine today still honours her legacy, in 2021 renaming its annual “Women of the Year Awards” the “Doris Anderson Awards.” In 2023’s Winter issue, Lenti wrote, “[Anderson] oversaw a progressive Chatelaine that covered everything from abortion rights and male dominance in Parliament to divorce and the wage gap….Sixty-six years later, it’s in her transformative and tenacious spirit that we recognize the recipients of our third annual Doris Anderson Awards.”

The eight-page spread features 11 women, including Lana Payne, a labour reporter and union activist; Rechie Valdez, the first Filipino woman to hold a cabinet position in Canada; and Asha Lapps and Erica London of the Black Queens of Durham Region, a grassroots group “all about community building and empowerment.” Lenti says, “I personally can’t imagine a Chatelaine that doesn’t do what Doris set out to do back in 1957, which is tackle these really hard-hitting issues that are affecting women and people across Canada. It is, to me, what makes Chatelaine Chatelaine.”

When Sally Met Doris

Even more than 36 years later, journalist and activist Sally Armstrong remembers the exact moment she first spoke to Doris Anderson “as though it happened five minutes ago.” It was the late 1980s, and Armstrong had just taken over as editor at Homemakers, a women’s service magazine that was a Chatelaine competitor. She knew she wanted to begin covering women’s issues, specifically women in conflict zones, but was unsure how to introduce that into a traditional women’s magazine. “I really wanted her advice, because I had plans for the magazine that would take it in a different direction, and I had so much respect for Doris Anderson and the way back in the day, she took Chatelaine in such a different direction that I wanted to talk to her,” she says looking back. She felt that by covering stories about women around the world, she would be bringing a new perspective to readers.

Armstrong had met Anderson at previous events and attended speeches she gave, but she wanted to get Anderson’s advice. So when Armstrong saw her at a book launch at the home of Anna Porter, then publisher of Key Porter Books, she knew she had to talk to her.

Armstrong was nervous, even a little intimidated. She had read Chatelaine as a young woman, becoming a fan of the editor who transformed the magazine throughout the 1960s and ’70s. For her, Anderson had captured in a way few others could the change going on for women as North America underwent a second wave of feminism. “But Doris Anderson did it brilliantly when she was the editor of Chatelaine, and she made a difference in the lives of women.”

Armstrong saw Anderson by the downstairs stairwell, with a crowd of people gathering around her. She thought, Now is my chance, and started inching her way toward Anderson, eventually coming close enough to speak to her. “Hello, I’m Sally Armstrong. I’m the new editor at Homemakers magazine, and I wondered if you might have time to talk to me,” she said. In her signature gravelly drawl, Anderson turned to her and said, “Well, Saaally, I would like that very much. Why don’t we have lunch?”

What followed was a close friendship, with the two talking almost weekly and Anderson acting as a mentor for Armstrong. “She said things to me over 20 years that I cherished, I appreciated, I absorbed,” she says fondly. Shortly after Anderson’s death in 2007, she wrote, “As a feminist, I picked up her torch and tried to carry the fire farther out from her blazing centre.”

Over the many years that the two were friends, Anderson offered a lot of advice, but what Armstrong remembers the most was something Anderson said early on in their relationship, when she wanted to know how Anderson would deal with covering more serious topics in a women’s magazine. “She said to me, if you have the readers, you can do anything because what the publishers want is the advertising dollar. And the advertising dollar follows the readers. So if you have the numbers of readers, they will get the ads, and they will leave you alone. That’s what she said to me,” recalls Armstrong. “And she was right.”

About the author

Julia Tramontin is a fourth-year journalism undergraduate at Toronto Metropolitan University. She is passionate about women’s issues and mental health, firmly believing that storytelling can be transformative. Her writing has been featured in publications like Her Campus. When she’s not editing, she can be found reading or hanging out with her dogs.