How current coverage of severe mental illness fails communities and fuels stigmas

K. J. Aiello vividly recalls the day their friend came home from the hospital. Their friend had just finished her last round of cancer treatments, and friends and family stood waiting outside of her house with a large “Welcome Home” banner. Everyone on the lawn was there to celebrate their friend’s triumph over illness. It was a beautiful moment.

Then, Aiello remembers the stark contrast they experienced on their own journey home from the hospital at 20 years old. No, they hadn’t recovered from cancer. And they hadn’t survived a horrific accident. They had returned from a psychiatric hospital. There was no banner and no friends and family on the lawn. “We don’t tell anybody,” said their mother, who had accompanied them on the trip home. “You’re gonna stop with this behaviour.”

It wasn’t the first time that Aiello had received this message. Their mom had once labelled a young boy who grew up across the street a “troubled kid.” “We say ‘troubled kid,’ but he probably had a pretty shitty upbringing,” Aiello says. Their mom’s advice was, “Don’t go outside. You see him, you turn around, you walk the other way, you come right home. You cannot be around him. He’s dangerous.”

The “troubled boy” was later diagnosed with bipolar disorder, but at the time, Aiello thought, It must be terrible being him. “It really ingrained in me how people perceive folks with serious mental illness like bipolar and schizophrenia.”

This sort of judgment was difficult for Aiello to process, fresh out of the hospital, and years before they were also diagnosed with bipolar disorder. “I was so ashamed. So ashamed.” Their mortification stemmed from more than just how their mom had framed their mental illness throughout their life. Psychiatrists and nurses in the hospital had also told them their condition was horrible—that it defined who they were as a person.

The stigmas attached to mental illnesses are perpetuated not only by friends, family members, neighbours, and strangers—they exist in the news we consume every day. Reporting contributes to what we know and how we feel about mental illness, and stigmas are made worse for those experiencing serious mental illnesses like bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and substance use disorder. But these stigmas are less pronounced for those experiencing anxiety and depression. Journalism is beginning to recognize and address these shortcomings, but there’s still a long way to go.

In 2019, the last year for which the World Health Organization made global data available, 970 million people suffered from a mental disorder, most commonly depression and anxiety. According to the agency, 31 percent of adults say mental illness is the biggest health problem their country faces, 20 percent of the world’s children and adolescents have a mental health condition, and suicide is the second leading cause of death among people aged 15 to 29. Studies suggest that stigma is most acute for those living with severe mental illnesses, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and substance use disorders.

But journalists are partially to blame for perpetuating this stigma. The Mental Health Commission of Canada’s most recent national strategy on mental health, released in 2012, says that its priority is to “increase awareness” and “reduce stigma.” Stigma-reduction campaigns aim to “improve the coverage of mental illness in the news media, which represents a major influence on public knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes.” Yet, mental health researchers say that a primary factor in the perpetuation of negative stigmas and stereotypes around varying mental illnesses is mainstream media. And because direct exposure to those experiencing illnesses such as bipolar disorder and schizophrenia are rarer than anxiety and depression, “the media is often the primary source of information about these conditions,” say Lara Antebi and Robert Whitley of the Douglas Research Centre and McGill University.

A study conducted by the Douglas Mental Health University Institute at McGill University found that 40 percent of Canada’s top newspapers linked severe mental illness to criminality, danger, and violence between 2005 and 2010. This is a decades-long narrative: In 2023, the Canadian Press highlighted a troubling uptick in violent crime across Alberta and British Columbia, linking the occurrences to gaps in mental health services. CBC’s coverage of the 2013 police killing of Sammy Yatim described the teen as a “disturbed individual,” referring to him as possibly “high or mentally ill” before his death. Tianhui Zhan, a teenager who stabbed a man in Glasgow, was characterized by outlets like BBC as “insane.” This language crafts a common narrative—and thus perpetuates stereotypes—about people experiencing mental illness. But the reality is that people living with mental illness are no more likely to commit violent crimes than the general population. Those experiencing severe mental illnesses are more likely to be victims of violence—four times more than those living without mental illness. In Alberta, for example, only three percent of violent crimes were attributed to mental illness.

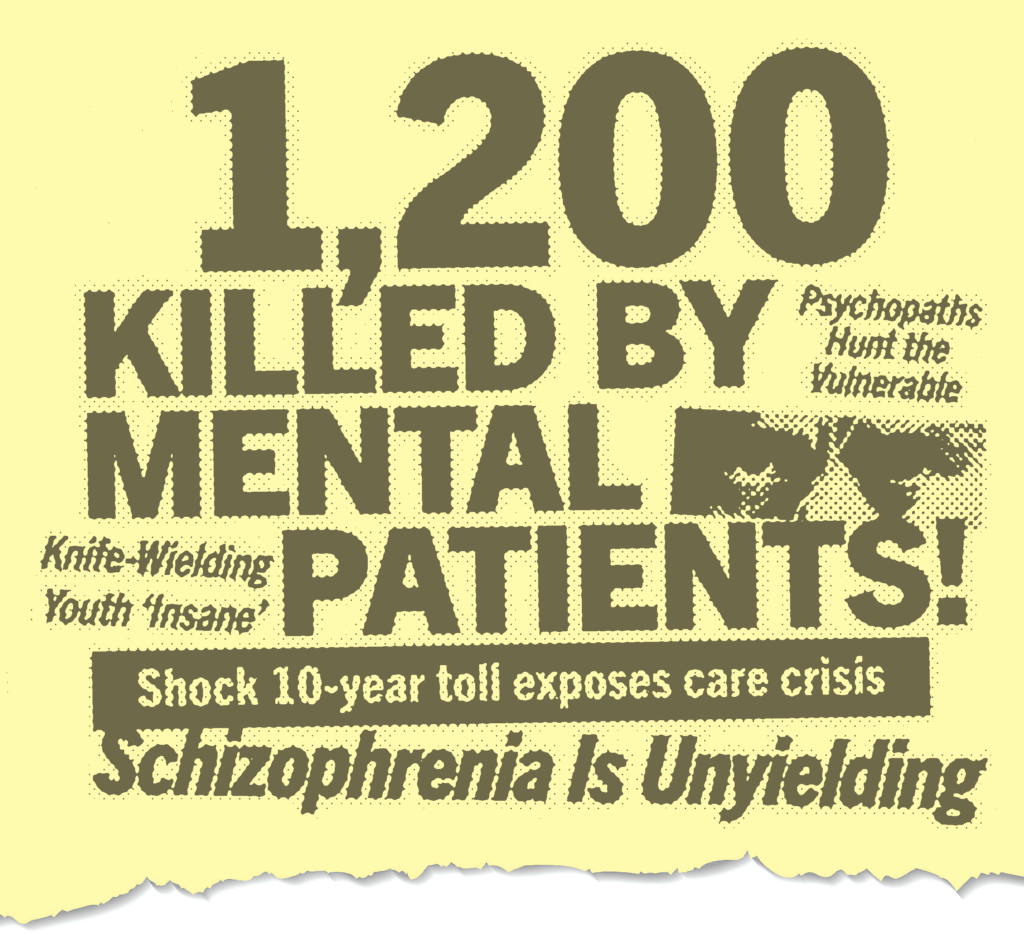

Over a three-month period and leading up to their 2022 study, Antebi and Whitley collected articles about severe mental illness. They found that 49 percent of these articles were positive in tone. That number rose to 87 percent for articles concerning more common mental illnesses like anxiety or depression. And 33 percent carried stigmatizing language, compared to the six percent contained in articles about more common mental illnesses. Examples of stigmatizing or stereotypical language used historically abound, with Toronto Star articles using such phrases as “psychopaths hunt the available [and] vulnerable” and “therapy with [psychopaths] is doomed to failure.” And the impact is grave. The stigmatizing language found in these articles “others” those living with mental illness. The person being represented or spoken about loses their identity. They are reduced to their mental illness.

The same study found that news reports on common mental illnesses were more than twice as likely to highlight rehabilitation. Experts were quoted in only six percent of articles about severe mental illness, while 27 percent featured quotes from individuals living with bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and substance use disorder. In contrast, 45 percent of articles concerning common mental illnesses included a quote from a person experiencing the mental illness mentioned in the story. Gavin Adamson, professor of journalism at Toronto Metropolitan University, says, “It’s just not representative of the kind of lives that people living with these conditions generally are experiencing.” Adamson has conducted extensive research into how severe mental illnesses are covered in Canadian news media. He says that focusing on the connection between mental illness, criminality, and violence is merely an easy way for journalists to cover the topic.

Some reporters say they don’t have the resources to cover these stories diligently. Aiello, a freelance journalist, says they’ve had difficulty convincing editors that these stories are worth spending time on because they don’t qualify as an “easy news story.” One reason for this is that it’s difficult to find experts to speak on the subject, as almost all requests must go through their workplaces’ media departments. In addition, reporting on severe mental illness is challenging because it requires additional time, energy, and resources. This sort of coverage also involves specialized training and speaking with—understandably—fearful sources. While negative stereotypes and stigmas are perpetuated by news media, prioritizing the voices of those who live with these conditions may be a positive step forward.

Seasoned reporters Nadine Yousif and Simon Lewsen agree that journalists need to be better trained to report on mental illness. Yousif, during her time at the Toronto Star, was one of the few reporters in Canada whose main beat was mental health. Lewsen has written comprehensive features about the subject for outlets such as The Walrus and The Local.

When she began reporting on mental health, Yousif says she received no institutional or professional training. She says she got input from colleagues but had to seek out resources on her own, like Mindset: Reporting on Mental Health. Resources for mental health coverage remain scarce. While guides made by the Mental Health Commission of Canada and the Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse and Addiction offer assistive information to journalists, Mindset remains the only journalist-to-journalist resource for mental health reporting in Canada.

Lewsen says he also had to figure out what reporting on mental health looked like as he went along. “I was definitely writing these stories before I had any training,” he says. Lewsen says he enjoys that journalism is not a “formalized profession,” where writers, producers, and other media workers need specific credentials, but believes training regarding sensitivity, and especially informed consent, are crucial.

One outlet told K. J. Aiello, “We’re already running a mental health piece this month. You can have more than one”

K. J. Aiello

Lewsen believes that the trickier aspects of stories concerning severe mental illness—including cases where individuals are found not criminally responsible by the judicial system due to a mental disorder—are how little they are understood and how they inspire less public sympathy. These are the stories that can make some editors skittish. According to a 2019 study published in the Journal of Mental Health, with contributions from Adamson, editors still tend to favour the mantra “if it bleeds, it leads.”

Adamson says he has noticed that when someone is dealing with anxiety or depression, the stereotype is: they’re weak. He also says that if someone is dealing with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, the stereotype is: they’re dangerous. To Lewsen, news reporting has made real gains in the first category, which is a great victory for society. “But,” he says, “I’m not sure if we’ve made as much progress towards getting away from the notion of people with psychotic disorders as dangerous.” And while Lewsen doesn’t feel journalists should stop reporting on violent incidents, he sees it as a question of proportionality.

Yousif says journalists sometimes have difficulty reaching certain people or factions of society because they don’t take the time to build connections. This is especially true when reporting on mental illness. “News organizations struggle to give reporters time and resources to build meaningful connections with those communities.” For Yousif, editors who understand what reporting on mental health looks like would benefit newsrooms.

Lewsen and Yousif also say they’ve worked with fabulous editors who have given them more time and resources to cover mental health stories, a trend that is on the rise in newsrooms. The goal is to keep moving forward.

Aiello has had many positive experiences with editors over the course of their journalistic career, despite knowing that some reporters still face challenges. Yet, Aiello recalls pitching a story concerning Canada’s failure to support those living with mental illnesses, which was shut down despite a well-meaning response. Aiello also reflects on an editor at one outlet who said, “Oh, we’re already running a mental health piece this month.” But, says Aiello,“You can have more than one.”

Yousif understands the frustration. “Newsrooms are sometimes a reflection of society, in the sense that society doesn’t understand mental illness as well as it should,” she says. “It’s a responsibility for us to learn these things because we are reflecting what’s going on in our community and giving voice to people who are rarely heard from.”

Yousif and Lewsen say trauma-informed reporting is the way forward. This means taking time to offer compassion to sources, being transparent about your role as a journalist, and explaining what your aim is with the story. In the newsroom, journalists can share tips and gain input from colleagues and editors who have reported on mental illness in the past. And, importantly, reporters should take time to consider the messages they’re sending out. “Am I amplifying harmful stereotypes about a vulnerable population by writing something a certain way?” asks Yousif, “or by omitting something?”

Aiello echoes these thoughts. “Trauma-informed reporting should be standard across the board. I don’t care how long you’ve been in journalism, you need to get training.” Part of that training needs to include learning about and understanding the history of what you’re covering, how it’s been covered in the past, and why certain approaches are problematic.

An essential step toward improving Canada’s coverage of serious mental illness is to include interviews with individuals of lived experience. “If the story is about psychosis, then you have to talk to people with psychosis,” says Yousif. “You can’t write a story about psychosis or somebody with psychosis without talking to folks who have that lived experience firsthand.”

Lewsen says journalists must modify some of the ironclad norms of journalism, such as being open to redacting information and obtaining informed consent. In current practice, sources have little control over their portrayal. That doesn’t work well for mental health reporting. When individuals with mental illnesses are interviewed, they tend to tell journalists a lot—sometimes more than they should. “In the old days, the journalistic norm was, ‘Well, if they said it, they said it. Nobody gets to retract anything they’ve said.’”

Fortunately, Lewsen says that mentality is changing. It may still apply when a journalist speaks to the prime minister or other media-savvy folks, but it shouldn’t apply to vulnerable individuals. Not every interviewee is the same kind of source, especially if the person is sharing intimate details about life and mental illness, and when a source shares a personal story, it ought to be viewed as a gift or offering. “You have a duty of care, and it’s okay to redact some things,” he says. “I’m not opposed to sending out a draft to a source if someone feels like they could be in some way harmed by your story.”

According to Lewsen, making use of long-form narratives is one way to offset stereotypes. “The best writers that I read on mental illness are long form writers,” he says. Such narratives allow for the writer to emphasize people rather than their illnesses. “You can represent the person behind the illness,” and delve into the interpersonal, neuropsychological, and social side of who they are. As Aiello notes, “Stats don’t change people’s minds; personal stories change people’s minds.”

Lewsen says journalists must continue covering instances where people living with mental illnesses commit crimes or acts of violence while making the decision to distance themselves from writing stories that reinforce perspectives focused on bad behaviour and criminality. When writing stories about crimes committed by people experiencing severe mental illness, “the correct language is tragedy rather than culpability. If someone dies in an earthquake, it’s tragic—nobody caused that earthquake. Same thing when someone has a psychotic break and does something violent. It’s tragic for the victim of that violence, and it’s tragic for the perpetrator who has to deal with the fact that they committed that violence they never intended.”

Mentorship is another path toward more comprehensive mental health coverage. Alternatively, journalists new to their beat can be paired with seasoned veterans or experts. “We can learn really fast,” says Aiello. “We’re resourceful. Quick learners.” A standard mentorship program for a mental health beat may encourage more thorough reporting, thorough reporters, and thorough stories.

Cliff Lonsdale, co-founder of the Canadian Journalism Forum on Violence and Trauma, an author of Mindset, and journalist of more than six decades, provides additional wisdom. “My starting point is, it’s not us and them. It’s all us. Recognizing the humanity in your subject, and that you share it, that is a really good starting point.”

Lonsdale builds on Lewsen’s insight that sharing work with vulnerable sources before publication is an accommodation that can be provided on a case-by-case basis. If a source ends up being uncomfortable with sharing crucial details, ask if there’s a way to rephrase them. “Nine times out of 10, you can work that out,” says Lonsdale. “If nothing else, it’s a way to fact-check your work, but it can make all the difference. It’s devastating to a person in that position if you get it wrong.”

Employing transparency while being honest about not having all of the answers, Lonsdale adds, can help to cultivate a connection between a journalist and their source—fostering thorough storytelling.

Throughout the process, journalists should explain to their sources why their stories matter and what might happen if they share them. “You can’t promise that it will happen, but that this is what I’m hoping to influence if I finally get people in my newsroom to understand this story properly,” Lonsdale says. And that could be enough to get the conversation started.

With files from Neesa McRae-McNicholls.

About the author

In his final year of the Master of Journalism program, Trent is always on the lookout for new challenges and his next adventure. After working for several years in advertising and publishing, he followed his passion and transitioned to journalism. Also acting as a Features Editor at The Otter, Trent uses the power of narrative to make large, complex issues like mental health more accessible, providing a human element that facilitates intimate connections. When he’s not working, he’s travelling, exploring the outdoors, reading anything he can get his hands on, and learning about a world which never ceases to fascinate and inspire him.