What went wrong for Metroland Media

On the kitchen counter in the childhood home of career coach Lisa Petsinis, there was always the phone, the calendar and every Thursday morning, the latest local and free print newspaper, the Scarborough Mirror. The Mirror circulated for more than 60 years. Her mother, Linda, contributed an article in 2018 about her grandfather, a First World War hero with a street in the neighbourhood named after him.

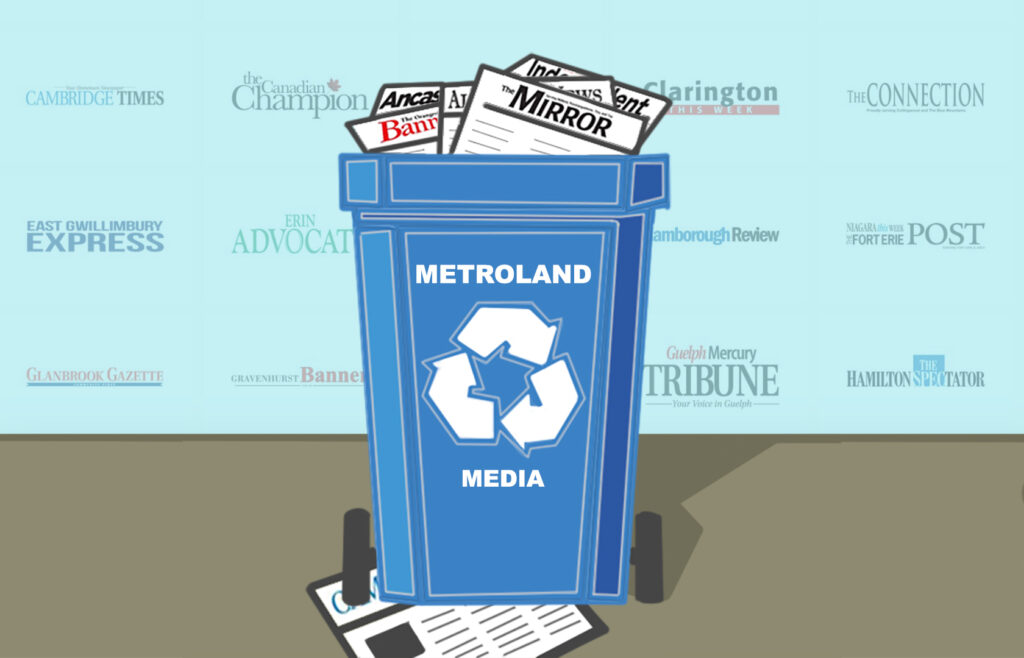

But the Mirror is now online-only, along with 70 other local print newspapers across Ontario, after regional newspaper publisher Metroland Media Group Ltd. announced its intention to pursue bankruptcy protection in September 2023.“Time with the community is going to be lost,” says Petsinis. “So then what? What’s going to fill the void?”

Metroland’s reasons for its bankruptcy proposal includes declining ad revenue from a decreased flier usage by readers and advertisers and condemnation of digital tech giants who take “the majority” of that advertising revenue. Meanwhile, working journalists struggle to serve their local communities amid the turmoil caused by recent decisions made in pursuit of that ad revenue.

(Un)making of Metroland

Metroland was established in 1981 when Torstar’s Metrospan Community Newspapers and Inland Publishing Company merged. Initially, Metroland published fewer than 25 weekly newspapers. Through acquisitions, it expanded to more than 100 newspapers during the 1980s and 1990s.

Metroland made money from ad revenue through its services of print newspapers and flier distribution. “For years, it worked pretty well,” says April Lindgren, a professor of journalism at Toronto Metropolitan University. Lindgren is the principal researcher for the Local News Research Project (LNRP), which tracks trends in local news media over time. “Advertising subsidized the cost of news gathering.”

Producing local news is quite important, according to Lindgren, because it gives the people in communities enough information to participate in their local democracy, hold power accountable, allow them to get to know other community members and, most importantly, have access to reliable information.

But things started to change, especially with the development of the internet coupled with the 2008 recession. “I saw two problems,” says Lindgren. “First, was local news organizations closing.”

Between 2008 and October 1, 2023, 511 local news operations closed in 342 places according to LNRP’s latest report. Seventy-seven percent of those closed news organizations were community newspapers. Only 212 local outlets launched in 150 places, suggesting a net loss of journalistic reporting over time.

In September 2023, 605 workers at Metroland’s local community newspapers—about 60 percent of the company’s workforce—and 68 out of 200 journalists were laid off as the company moved its print newspapers to an online-only format. “When we see major developments like [the Metroland layoffs] the problem is that they laid off people who produce those newspapers.”

Stretching Local Journalism Dollars

Mike Adler is one of the journalists affected by the lay-off announcement in September. His bylines are a mainstay in the Mirror, where he’s been working for the last 27 years as a staff reporter at Metroland. He noticed a change in the look and read of the newspapers as a centralization of authority happened at the company. He says that eventually, only one person was in charge of the content and the appearance for the entire group of newspapers, which represented a diversity of communities. Adler watched content go from human-driven to more data-driven as the newsroom slowly shrank. “I was in a struggle between writing stories about Skittles or what was going on at the local hospital. There were things that I had to accept, but didn’t like very much.” says Adler, adding that many of his colleagues quit.

“That is not about producing journalism in the public interest, it’s producing journalism in the interest of the business,” says Lindgren, referring to this change in content.

Joanna Lavoie left Metroland in spring 2022 after working as a staff reporter at Metroland’s Toronto communities division for 17 years. She says some of the content was AI-generated and click-driven. “It was kind of soul sucking…we were busting our butts to write really interesting local news, but I guess that’s what pays our bills.”

Until it doesn’t. So, what happens when the local news organization closes?

“People say, ‘Well, who cares? There was hardly anything to read,’” says Lindgren. “‘What there was, was not that great and questionable. I’m not sure I trusted it.’ And so, we end up with nothing. I think people don’t really understand the consequences of nothing.”

But to produce something costs money. “Advertising revenues have been shrinking significantly,” Lindgren continues. “The dilemma for news organizations is, where [should] the money come from?”

A Heated Summer: Billing Big Tech and the Merger

For Jordan Bitove, the answer is big tech. Bitove is a businessman who has said he has no journalism experience. He partnered with Paul Rivett to acquire the Torstar corporation, Metroland’s parent company, in 2020. In November 2022, Bitove and Rivett split, leaving Bitove as the owner of Torstar. He lobbied for Bill C-18, the Online News Act, which was first introduced in April 2022 and would force big tech companies, namely Meta and Google, to share the revenue they get from linking to Canadian news media content with Canadian news media companies.

In June 2023, the bill became law. In response to the bill, Google released a statement saying they would block linking to Canadian news which they called “unworkable” and the “wrong approach” to supporting Canadian journalism.

In the same month, Bitove’s Nordstar and Canadian news media company Postmedia Network Inc. entered non-binding merger talks. They wanted to pool their resources so they could compete with big tech companies and ensure the “viability” of the Canadian newspaper industry.

The merger would’ve seen Postmedia and Metroland combined, and the Toronto Star managed by a new company. But Postmedia is in debt and also struggling with a decline in advertising revenue. The company announced it would lay off 11 percent of its editorial staff on January 24.

Merger talks ended in July 2023. Nordstar cited “financial uncertainty” for the merger not going through, but Postmedia CEO Andrew MacLeod said that was “inaccurate” and blamed the “unstable landscape” caused by big tech’s objections to Bill C-18.

Meta soon responded to the legislation by blocking Canadians’ access to news on its platforms: Facebook and Instagram.

Here Come the Layoffs

On the morning of Friday, September 15, 2023, a former Metroland staff reporter who wishes to remain anonymous says they were working on a long-form feature about African asylum seekers for their regional paper when they received an email calling for an urgent meeting.

The reporter, next to his colleagues, listened to Neil Oliver, Torstar’s chief executive officer read off a paper to announce layoffs, effective immediately. “I think Metroland was like the step-sister that came along with the Star,” says Lavoie. “It became more of a problem than an asset.”

Unifor Local 87-M, the local union which represents 104 of the workers, said it was not given an opportunity for dialogue before the announcement, despite being in “weekly meetings” with Metroland. Workers are still under contract until December 31, 2023. According to documents filed by accounting firm Grant Thorton LLP, Metroland actually owes $16 million to its employees and $41.6 million to Torstar, its parent company and largest creditor.

Adler fears this is not just the end of his journalism career—it’s foreboding for future journalists in general. “We need a new [business] model,” says Adler. “I don’t know where that model is going to come from, [but] it’s not going to come from the generation of newspaper executives that is currently in charge.”

About the author

Daysha Loppie is a fourth year undergraduate student in the journalism program at Toronto Metropolitan University. Her work has been published by the Toronto Star, West End Phoenix, ByBlacks and The Local. She’s interested in long-form feature writing and primarily covers Black communities, social justice, business, arts and culture.