Photojournalism has an exploitation problem. Three journalists are finding ways to solve it

Daniella Zalcman was in Australia at AIDS2014, a conference organized by the International AIDS Society, in July 2014, when she read a report on the alarming rates of HIV infection by UNAIDS, the United Nations program aiming to end AIDS as a public health threat by 2030. After reading the report, she applied for and received a grant from the Pulitzer Center to photograph the issue in First Nations communities in Canada. Zalcman, a New Orleans-based documentary photographer whose work primarily appears in National Geographic and The Wall Street Journal, headed to Indigenous communities where the spread of HIV was most prevalent due to the use of injection drugs and opioids. She spent time with the people she photographed, learning about their lives and struggles, trying to find a way to document them. But when she got home and reviewed what she had captured, Zalcman felt uneasy. “I realized the work wasn’t very good. It didn’t feel particularly ethical to publish it. We all know what those photos look like; we’ve all seen versions of those images. They don’t really add to any conversation. They don’t really help us learn anything more about the people I was spending time with.”

Something else was troubling Zalcman. She knew this story wasn’t just about addiction and healthcare. After arriving in Canada, and while researching this project, she slowly discovered what Indigenous communities had endured for generations. She realized she had been working on a public health story without context. That led to more research and a deeper interest in the effect of residential schools. “I had never learned about them in my own history classes,” she says. “And we invented those boarding schools in the United States. So, I realized that I had to completely scrap the story that I thought I was working on and pivot to looking at the history of the boarding schools.” She returned to Canada a year later, and on a different mission.

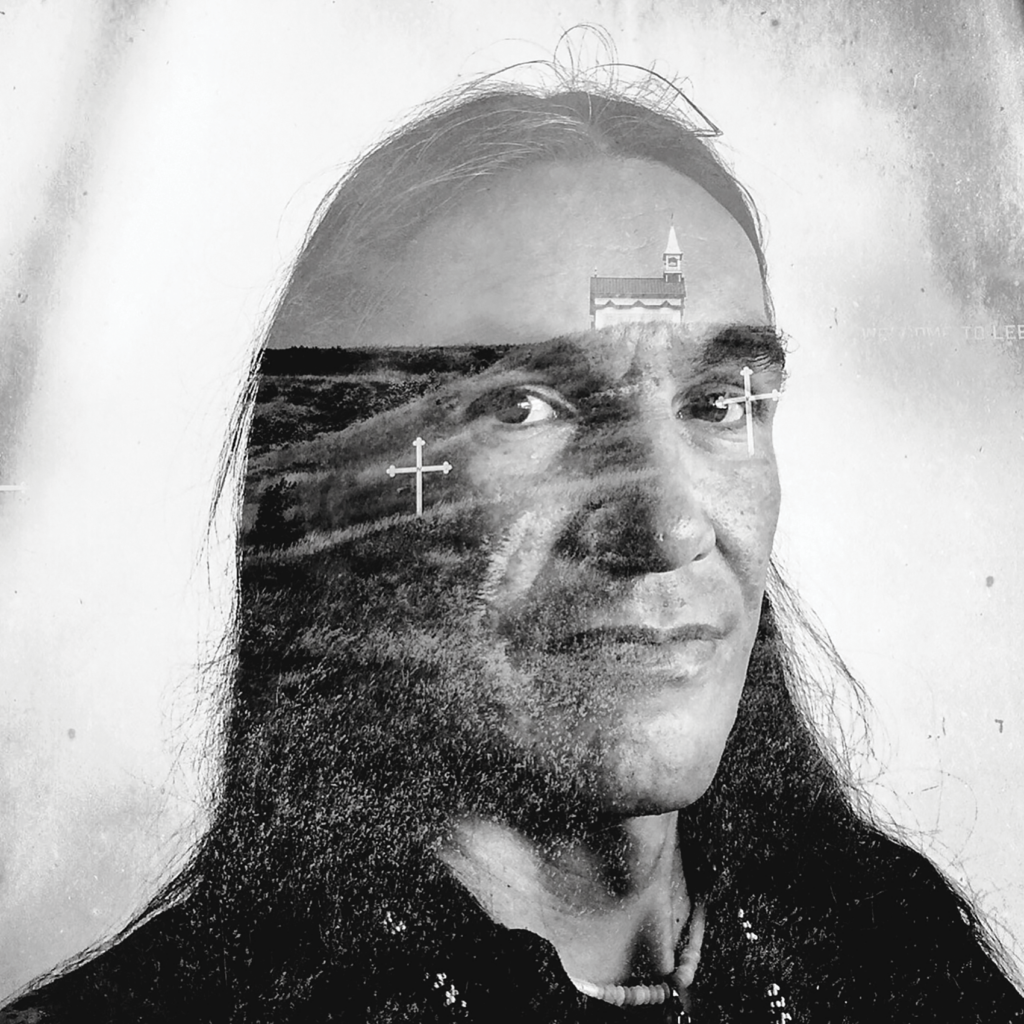

Her portrait of Elwood Friday is the result of a shift in the focus of Zalcman’s project, and part of a 10-year-long endeavour that resulted in her photography book, Signs of Your Identity. Abandoning parachute journalism, the practice that briefly drops a reporter into an area in which they have little knowledge or experience to report on a story, for a deeper examination of people’s lived experience, Zalcman captured Friday superimposed against the background of St. Philip’s Residential School, in Saskatchewan, which he endured for two years. “I’ve never told anyone what went on there,” Friday tells Zalcman. “It’s shameful. I am ashamed. I’ll never tell anyone, and I’ve done everything to try to forget.”

To capture Friday and others, Zalcman shot double-exposure portraits of the boarding school survivors. The portraits of the individuals she interviewed were then overlaid with images of the sites and captioned with memories of their residential school experiences.

Zalcman’s work is now centred on the legacies of Western colonialism, and her process involves investigating not only what or who she is photographing but also how the audience will understand it. “When it comes to violence and depictions of violence, we need to have more nuanced conversations about what our objectives are for our work, and think about the fact that our audiences are now all consuming more images a day than humans ever have in the course of our history.”

The ethics surrounding war reporting and photography are regularly debated. Subjects are depicted in vulnerable positions and often have no say on being photographed. According to a study published in The International Journal of Press/Politics, children are considered ideal subjects because they are the perfect example of the senselessness of war. A study published in the International Journal of Communication assessed the effectiveness of gruesome photos and to what extent they influence audience action. “The Distant Sufferer: Measuring Spectatorship of Photojournalism” noted images of child victims are rewarded in photojournalism communities and attract public attention, even though such images violate children’s right to privacy. The Terror of War, one of the most famous examples of photojournalistic images, depicts a naked girl running away from napalm explosions in the Vietnam War. In 1973, the photographer, Nick Ut, won the Pulitzer Prize and the World Press Photo of the Year for the image.

Forty years later, in 2013, Dutch academics Marta Zarzycka and Martijn Kleppe studied 322 photographs of war, disaster, or conflict that had previously won the World Press Photo Contest, which recognizes the best photojournalism and documentary photography. Their research showed that 120 of the photographs exhibited common tropes, such as corpses, battlefields, and survivors among ruins. In addition, women were more frequently represented as passive mourners, being rescued.

The belief is that photographs can affect major decisions, both assailing the public’s conscience and challenging power brokers to action. Yet, researchers Teresa Weikmann and Tom Powell, who authored the 2019 “Distant Sufferer” study, question that assertion. For example, The Terror of War has been credited with ending the Vietnam War. In fact, the study found that while the image may have led to public outcry, there is no evidence that it had any effect on political decision-making.

Even in the most horrific of cases, audiences tend to have fleeting interest. Take, for example, the 2015 photograph of Alan Kurdi, a two-year-old Syrian boy lying dead on the shore of the Mediterranean Sea. The picture went viral and caused an international outcry. However, an article by the Poynter Institute for Media Studies concluded that “it was a photo that shook the world—or at least the media—for a few days. But not much more than that.” A report by the European Journalism Observatory found that European newspapers had reverted to regular reporting within a week.

Some editors now question these graphic approaches and their capacity to perpetuate stereotypes. In 2018, National Geographic’s newly minted editor-in-chief, Susan Goldberg, apologized for the publication’s racist past: “Until the 1970s National Geographic all but ignored people of color who lived in the United States….Meanwhile it pictured ‘natives’ elsewhere as exotics, famously and frequently unclothed, happy hunters, noble savages—every type of cliché.” The editor promised to do better.

Meanwhile, photojournalists like Zalcman, Andrew Jackson, and Sebastián Hidalgo, among others, have defined independent approaches to their work, keeping colonialism and its intergenerational and intercultural impacts in mind. They ask: What is the purpose of the images? Who is the audience? What do they depict? And how can they do this work with care and sensitivity for the people and the stories they document?

“I’ve seen photographs by award-winning white photographers who have photographed children who have been raped and these children are posed in ways where they’re semi-dressed. And these images win awards. Now, if you were to take that photograph of a young child who had been assaulted in the Global North, you will be arrested, and you’ll be sent to jail,” says photojournalist Andrew Jackson.

For many years, the Pulitzer Prize winners for feature photography have been celebrated for capturing highly sensitive images, from the devastation caused by COVID-19 in India, to the violence Rohingya refugees faced in fleeing Myanmar, to the famine in Yemen. “Why is it that you’re able to show dead Black people and dead brown people in graphic ways and images and in newspapers in the Global North?” asks Jackson, a Montreal-based photographer, writer, and educator who sits on the advisory panel of the Photography Ethics Centre. “But white people aren’t photographed and shown in the same way in the Global North. And we have to ask ourselves, why does that happen? And perhaps in one sense this maintains a status quo of civilized and uncivilized.”

Jackson acknowledges that it’s hard to make a conscious decision to work differently. Early in his career, he, too, felt the need to capture images similar to what he saw in the media. While taking photos inside a South African trauma unit in 2006, he was brought by a doctor to the mortuary to see the body of a man who had just died. “You’ve come to see our people live, you need to see how they die,” the doctor said.

The mortuary had a tin roof. It was 40 degrees outside and maybe 30 degrees inside. Jackson took a photograph of the dead man, focusing on his limp hand. As he prepared to shoot, he considered several things: “The aesthetics of this image, the composition, the light, all those different questions, taking my light meter readings, and so forth.”

Loading a new roll of film, Jackson noticed a bow tied on the man’s shoes. It was a small detail, but it felt significant. He found himself thinking about the man and who he was. When he returned home, there was interest in the photograph of the man’s lifeless hand. “Somebody wanted to buy the photograph. Nobody asked me who this person was, or what happened to them, what had gone on in their lives for them to end up in this moment in time. They just said, ‘Wow, that’s a nice photograph.’ And I started to question, well, what is the point of this type of photography?”

He realized that context and depth can get lost once an image is taken. “As photojournalists you travel around the world, photographing chaos, death, and destruction. It doesn’t matter whether this is a dead child in Haiti or a dead child somewhere in Africa or Southeast Asia or whatever. It’s just the composition. That is a dangerous thing, if we just see people in crisis as compositions.”

It is the sort of approach that we see in Stepping Over the Dead on a Migrant Boat, a 2016 photo-essay published in The New York Times. The story is about migrants from sub-Saharan countries, such as Eritrea, Ethiopia, Somalia, and Nigeria, attempting to reach Europe. Two of these images, along with the accompanying text, depict dozens of migrants dead due to asphyxiation. The images show survivors stepping over dead bodies and men and women, visibly in a state of panic. The photo-essay ends with a quote from photojournalist Aris Messinis: “I’ve seen a lot of death, but not this thing. This is shocking, and this is what makes you feel you are not living in a civilized world.”

Some exhibitions have taken a more thoughtful approach to people in crisis, such as a 2018 Open Society Documentary Photography Project called Another Way Home, which explored the topic of migration through documentary photography. The difference in this exhibition is that there are no graphic images of migrants suffering. One example stands out: Thana Faroq’s The Passport. Faroq is a Yemeni photographer who documented her own journey from Yemen to the Netherlands. Faroq changed the name of this project to I Don’t Recognize Me in the Shadows, which was published as a book in 2020. The project also depicts refugees with handwritten letters in which they shared their experiences. This series of Jackson’s images, titled From a Small Island, highlights the familial effects and consequences of migration. From a Small Island is now available as a book that examines the legacies of Caribbean migration to Britain.

It’s important to think about photography as a way to share information, says Sebastián Hidalgo, a Chicago-based photographer who covers social and humanitarian issues, mostly at home. But for Hidalgo, the circumstances are important. “Information in any form is super-useful to some degree, but within the context of how you will use this information to further the need for change, or to further the need for social justice.”

The way to combat shock-value journalism is by having continuous conversations with editors and reporters—and most importantly, being as transparent as possible with the subject of the photo. “A lot of the things that I photographed are highly, highly sensitive,” Hidalgo says. “It’s important for us to establish rapport or establish a way of communicating that it feels comfortable for both parties.”

In a series of images published in The New York Times, Hidalgo captures the different aspects of his home base, Pilsen, a neighbourhood in Chicago, before it changes with gentrification.

A trauma-informed approach is critical. “A cold phone call might not be [effective],” notes Hidalgo. “Maybe the person feels comfortable texting. So that’s our form of communication. Once you get that, and you explain the process and how it works, you can begin to do the interview process. What I like to do is ask really surface-level questions in the first interview, so that they can kind of get familiar with the process. And then, later on, if you’re comfortable with me, then you can kind of direct them and they make a portrait.”

Hidalgo’s project Midwest is a collection of images that look into how “millions in the Midwest and Texas undertake laborious efforts to maintain a sense of belonging when systems fail in the United States.” The photographs are taken at highly sensitive moments.

“Once that rapport is established,” says Hidalgo, “and those basic questions have been answered, we can review, revise, draft another couple of questions, go back to the person that we’re interviewing, and get deeper into the hardest things.”

What makes the ethics of photojournalism a challenging conversation is that the practice is entirely situational. There are no universally accepted, mandatory guidelines. Even journalistic principles that newspapers and magazines follow differ, often leaving room for interpretation. The Independent Press Standards Organisation, which represents many U.K. publications, states, “It’s unacceptable to photograph individuals without their consent, in public or private places where there is a reasonable expectation of privacy. The concept of a ‘reasonable expectation’ of privacy is a problem confronted every working day by photographers.” Organizations and associations themselves recognize that the photographer makes the final decision on how to capture an image.

Then there is the role of the organization that publishes the images. Andrew Jackson isn’t convinced by National Geographic’s commitment to change. He highlights that not too long after the new editor-in-chief’s statement, it ran “a story about the American West, with an image of a cowboy, and an Indigenous American person, and they had the same old stereotypical tropes, about Manifest Destiny and cowboys. Nothing’s changed. People don’t mind pretending to create seats at the table when times are good. When the economy dips and tanks and things are bad, all those initiatives suddenly go out the window.”

The onus falls on individual photojournalists to shift the narrative through their work.

In a photography project commissioned by England’s Birmingham City University, Jackson sets out to capture the housing crisis in the U.K. The result was The Promise of the City, a commentary about social housing through a specific portrait of residents of a single tower block set to be demolished in Birmingham. Individuals living in these buildings were being forcibly relocated across the city. “It’s all about collaboration and permission,” he says, reflecting on his process. “There were lots of people that didn’t want to be photographed. So, I didn’t. But also, those who didn’t want to be photographed, I asked, ‘Can I photograph your space or the spaces you’re leaving behind?’”

Before going on location, Jackson prepares himself by doing research. For this project he dug into histories of postwar urban development, surveyed academic literature, and conducted his own original research. Daniella Zalcman’s process also involves research and legwork. In a lot of communities, particularly those that have been historically misrepresented and maligned by traditional media outlets, there tends to be a little bit of hesitancy when journalists attempt to reach out by email or phone. “I am always doing a ton of reading in advance,” she explains. “I want to know what other journalism has been done in that community. I want to know what exists in terms of academic writing.” It’s also about building relationships, transparently. “For me,” she continues, “it’s to show my face around town and get to know people. And that usually is the best strategy.”

Care is at the centre of Sebastián Hidalgo’s approach. “A friend once told me that ‘understanding people is not as important as loving them,’ which I take as a lesson to approach with love. Imagine if we attempt to love people instead of extracting information from them how trusting journalism can be.”

About the author

Iman is a fourth-year journalism student at Toronto Metropolitan University. She is a writer who has a deep interest in stories from the Global South. In her free time, she enjoys reading and watching movies. She loves to explore new stories and understand different perspectives.