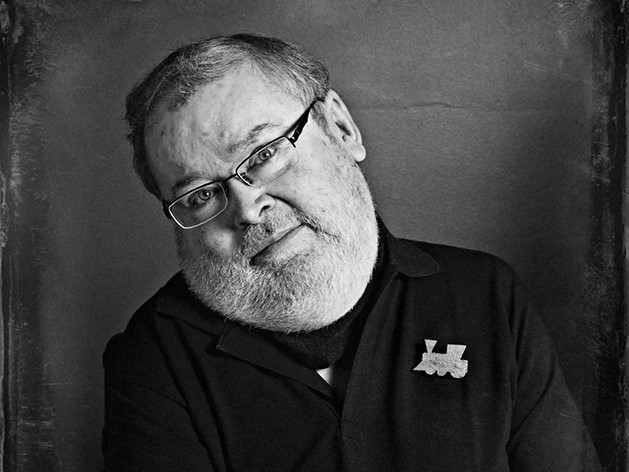

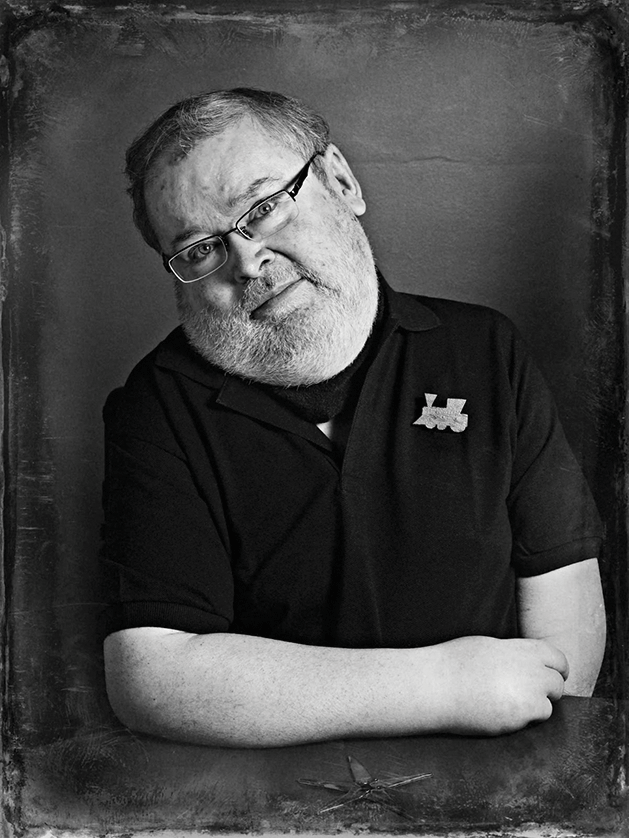

Stephen Trumper’s 25 years of brilliance, empathy, and endless patience at the J-school

Stephen Trumper was immensely talented, whip-smart, and exceedingly kind. He scaled the heights of the journalism industry, gaining more respect from peers than any accolade could ever recognize. He was a giant of magazine editing and a strong disability advocate. Yet he is most fondly remembered for small deeds, like always finding time for his students and giving candid advice over coffee.

I met Steve in 2015 during my first year of the master of journalism program at Toronto Metropolitan University, where he taught for three decades at the School of Journalism. I was writing about accessibility on campus and had asked to meet with him to chat widely about the subject. Though I didn’t realize it at the time, I was lost in my story and in desperate need of an experienced editor to anchor me.

Steve was a dream interviewee—attentive, illuminating, and forgiving of questions that revealed my inexperience with disability. He was not, however, about to become my de facto editor. Amused, he tiptoed around what I really needed—direction—as though he knew some good would come from finding it for myself. As an instructor, Steve liked to guide and protect with an invisible hand. When you felt you were on your own, his hand was right there behind you, holding you up. You often didn’t even know it existed.

A year after I met him, I learned that my earnestness had made an impression on Steve. He saw in me the ability to be editor-in-chief of the Review of Journalism. With his encouragement, I applied and got the role. This set the tone for what would become a recurring theme after graduation: my asking Steve to be a reference, his accepting unequivocally, and then his remaining positive when the job never materialized—until one finally did.

Sometimes, his hand wasn’t so invisible. And sometimes, it was downright dirty. Oh, yes, on occasion you felt as though he was using it to set you up. Steve’s face would betray that he knew more than you, and he wasn’t about to fill you in on his secret. Early in our tenure as a masthead, for example, Steve proposed that we conduct an audience research survey to gauge what working journalists thought of the Review’s work. This was after we had spent an entire class “pissing” (his words) on the work of our predecessors, believing our year would easily be the best in the magazine’s history.

“The people who write for it are children.” “You have watchpuppies.” The feedback we received from prominent journalists in our survey formed the backbone of my editor’s note that year, which Steve edited—gleefully.

Steve’s skillfulness as an editor was well known. As the year progressed, his abilities as a teacher revealed themselves to be as strong. Friends of mine from the Review have commented on how perceptive he was. One noted that he understood the social dynamics of our cohort more than we realized at the time. This was as much a natural gift as it was the result of giving endlessly of his time. Another former Review editor recently told me, “Steve actively taught, in the usual sense, as much as he commiserated, which in retrospect may have been the secret sauce to his method.”

Steve’s interest in you was always genuine. Your life, career aspirations, relationships, and struggles—these were as often the topic of casual, after-hours conversation as the work itself. He developed such a deep understanding of his students that he knew if the moment required a teacher or a steady, indiscernible hand.

We would visit his office to ask, “Steve, when exactly does the magazine ship? How many days do we have, really?” He was unflappable: “Just let me worry about that,” he would say. He chastised us for dragging our feet—from filing drafts to fact-checking to writing display copy, we were consistently steps behind schedule—and now he didn’t seem to care about deadlines at all. We were puzzled.

There was no reason to be. Though Steve’s hand could craftily get results, it was mostly there to protect. As we stressed about putting together a magazine for the first time, Steve knew from experience that the added weight of shipping dates wouldn’t help.

When the final day of production arrived, there was still work to be done. A few of us, including Steve and our art director, Dave Donald, worked long into the night finishing and proofing pages. At a certain point, it was time for Steve to get home. From the comfort of his bed, he continued signing off on pages until three or four in the morning. During one long, emailess stretch, we thought he had fallen asleep. Maybe he had for a moment. But there was no way he was going to give up on us now!

Through knowing Steve only a handful of years, I have come to believe he was born to be a teacher and fell into journalism through a stroke of luck for the industry. Even his editing style carried the hallmarks of a teacher: empathy, brilliance, endless patience.

Whether you were his writer or his student, the story was yours to write. He still found a way to shape and empower it.