O Jornal de Toronto united the city’s Brazilian diaspora. As the paper struggles, the community risks losing its cultural meeting point

One day, you decide your life needs a change. You’re successful, but looking for new challenges and you want to start fresh. “Let’s move to Canada,” your partner suggests, and you agree. That’s how it starts. You gather the documents, sell off your publishing house, get your visa, and prep the application. After a few months, it’s all done, and you’re off. Now what?

That’s what Alexandre Dias Ramos did. After living in Porto Alegre, Brazil, for eight years, he grew exhausted by the work and the city. He and his wife wanted to leave. Their first idea, though, wasn’t Toronto. It was Lisbon, Portugal. But then, after spending a month in Mississauga in 2012 with his now ex-wife’s family, Toronto became the front-runner.

After landing in Toronto, in 2013, Ramos got to work. Though there was already a magazine project in the back of his mind, he began his work in Toronto as an art curator. Four years later, and now as a Canadian citizen, Ramos launched a community newspaper for the burgeoning Brazilian immigrant population choosing Toronto, as well as all Portuguese-speaking readers in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA). “Jornal de Toronto was born out of necessity,” he says, recognizing the need for a medium that speaks not just to Brazilians living in Toronto, but all Portuguese-speaking readers.

According to the 2021 census, there are around 21,755 self-reported ethnic Brazilians living in the GTA, 15,425 immigrants from Brazil and 5,795 who had immigrated to the GTA within a five-year period. The general consul of Brazil in Toronto, Wanja Campos da Nobrega, explains that the data from the Canadian census is partial and segmented, making it difficult to be certain of the number of Brazilian residents in Toronto. It’s possible to say, however, that there are at least 17,000 living in, or near, the GTA. This number represents the individuals who have transferred their voter registration from their address in Brazil to the Toronto consulate to be able to vote abroad. This migrant population is also relatively young, says Campos da Nobrega. Recently, “the profile of Brazilian migrants has increasingly been made up of young people and young couples with young children who, attracted by the very liberal Canadian migration policy, arrive in the country to start or restart their professional and family lives,” adds the consul general in an email, saying that high school and university students follow close behind as a large part of the Brazilian migrant population under their jurisdiction.

As Brazilians living in Toronto, these individuals are stranded between two worlds. They have difficulty connecting with the sizeable, and old, Portuguese community in Toronto—which numbers around 85,000, according to the 2021 census. Although they share a similar language, there are still many differences in the use of words and accents, which could potentially make articles written in Portuguese by someone from Portugal seem quite odd to a Brazilian audience. Portuguese immigrants have been here longer, with most of the diaspora occurring in the 1950s. The consulate general of Portugal in Toronto explains that many of these 1950s arrivals were recruited to work in rural and isolated locations in Canada, but soon established themselves in the larger cities. According to the consulate general, many of the first generation of Portuguese immigrants are concerned with maintaining their Portuguesismo, or “Portugueseness,” though, among the second generation, intermarriage with a non-Portuguese spouse occurs occasionally. On the other hand, the Brazilian community has members still looking to establish themselves. Brazilians are also distanced from the rest of the Latin American community. They may share a continent, but they don’t share the same language: Spanish. This means local publications and businesses in either of these communities aren’t easily accessible to Brazilians.

Ethnic media like Jornal de Toronto can be crucial for immigrant communities in Toronto. In a city where just under half the population has been born elsewhere, it can be hard to feel at home. Local papers in your language, with your needs in mind, can make all the difference. Ramos argues that big outlets such as the Toronto Star and The Globe and Mail are essential, but so are the little ones: “The ethnic media can talk to the small guy, the person with a small business that has importance in a community. That’s something a big paper won’t really do. The local papers know who’s who in the community.”

When Ramos arrived in Toronto, he decided to put his lengthy education—his bachelor’s degree in the visual arts, his master’s in the sociology of culture, and his doctorate in history, theory, and criticism of art—to good use. He had also spent the last 14 years directing Zouk Books, a Brazilian publishing house specializing in art and sociology. With these skills in mind, alongside his experience as an academic editor, professor, and researcher, he decided to make something new. Tying up loose ends in Brazil before coming to Canada, he sold Zouk Books, which is still on its feet, though under different ownership. “I couldn’t take it anymore. If I were to do anything, it would be a magazine or a newspaper. That idea was stuck in my head for a while.”

Botelho noticed that with the pandemic, many publications either closed down or shrank. There’s no longer, physically, a place for magazines

Starting in 1986, Brazilian airline Varig established a direct flight between São Paulo and Toronto that lasted until 1994. In the 1980s, Varig was averaging 14.21 million passengers per year, to 43 domestic cities and 42 international, including Montreal and Toronto. They were considered tourists, but according to one source, R. Paoletti, many return flights had fewer passengers. This was not unusual. In the case Singh v. Minister of Employment and Immigration, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that “the legal guarantees of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms apply to ‘everyone’ physically present in Canada, including foreign asylum seekers.” That meant that Brazilians coming to Canada, for example, had the right to a full oral hearing of their claims before being admitted into the country or deported. This process was, of course, long and oftentimes delayed, which meant many immigrants were waiting indefinitely without the ability to work until granted a permit or to access other benefits granted to Canadian citizens.

The immigration point system, which began in Canada in 1967, is weighted such that people with higher levels of education and work experience will have an easier time entering the country, according to the Government of Canada’s website. Ramos, who fits into this group of educated immigrants, saw an opportunity to create a periodical for them, along with other Portuguese speakers across the GTA. His initiative would later turn into Jornal de Toronto.

Much of Jornal de Toronto’s content is evergreen and aimed at bettering the community. Most stories have an educational intent, which, Ramos says, the community appreciates. He says two of their most-read articles are on seasonal depression and whether it’s possible to sue someone in Brazil while living in Canada. From the start, Jornal de Toronto set itself apart in many ways: it actually paid some of its writers, and unlike at other ethnic publications, Ramos is not running the Jornal de Toronto on his own. The paper has an editorial board of which the editor-in-chief is just another member.

One of the main goals of this publication is to serve its community of Brazilians living in Toronto and anyone else interested. About Jornal de Toronto’s purpose, Ramos says, “I want people to come out of reading an edition, or even just a story, as a slightly different person than the one that started reading it.” But even with a passionate team and a lot to say, Jornal de Toronto, much like many other local publications, is struggling. With the COVID-19 pandemic and the growing economic challenges of living in the city, the paper has stopped printing since 2020 and has grown smaller in size.

Ethnic media not only help to create a better sense of unity in a community—they can improve lives. From 2017 to January 2023, Camila Garcia, a Brazilian immigrant, cohosted Focus Portuguese alongside Sérgio Mourato, a Portuguese host. There, she interviewed Brazilian immigrants living in Toronto about their experiences in the city. One time, she says, she talked to an architect about her struggles as an immigrant to use her Brazilian architectural degree. After the discussion, the architect told Garcia that several people reached out to her with either work opportunities or to tell her the interview had inspired them to pursue architectural work in Canada. To Garcia, ethnic media is a “meeting point for the community. You can see that there are possibilities.”

The show explored news stories in both Brazilian and Portuguese local communities, which she says are quite different. Garcia says Toronto’s Portuguese community’s biggest concern might be along the lines of, “My grandson doesn’t speak Portuguese anymore,” whereas the Brazilian community is worried about getting established and making money. In her work as coanchor of Focus Portuguese, Garcia presented news relevant to the community in her language. “One of my goals was to instruct members of the community on how things work here.”

Garcia was also a writer and member of the editorial board for Jornal de Toronto. There, she wrote about politics, both in Canada and Brazil, based on what was relevant to a Brazilian-Torontonian audience. The paper, she says, reflects on a lot of the issues of being Brazilian and living abroad. “Out of the Brazilian publications in Toronto,” she says, “Jornal de Toronto is certainly the most interesting one.”

Jornal de Toronto’s longtime columnist, José Francisco Schuster, talking about Ramos’s initial idea for a Brazilian publication, said he was glad it didn’t stay in Ramos’s head for too long. He says it’s “added a quality filter” that did not exist in community media. “It’s the first community media I know that focuses on quality,” he says. “Even with all its limitations, Jornal de Toronto is still able to maintain a really good standard.”

Schuster came to Toronto in 2000, looking for a better, more economically stable life. He chose Toronto because the flight from São Paulo landed directly in the city. Schuster is not merely writing as a hobby—he is a journalist. In Brazil, he had notched over 20 years in newspapers and radio stations. In Toronto, he looked to continue but was quickly faced with the harsh reality that publications here didn’t want him, at least not in a paid position.

Schuster says that even after taking a year-long college course for internationally trained journalists, which promised to make their job hunt easier, it was almost impossible to support himself as a journalist in the city. “The problem isn’t really the language. It goes deeper than that: they’re looking for Canadian experience.” To get Canadian experience, you need Canadian experience. “It’s like that egg and chicken story. It’s an infinite cycle,” Schuster says. With this conundrum in mind, Schuster turned to ethnic publications—where he wouldn’t be able to support himself financially but he would do what he loves.

Schuster was able to maintain a handful of jobs here and there in journalism, mostly volunteer-based, and one paid journalism job as host of a Brazilian radio show on CHIN Radio called Noites da CHIN—Brasil. The show lasted almost two years until it was cut in November 2019 for lack of advertising. He would go on to host a successful interview podcast for Jornal de Toronto called Fala Toronto. Schuster says it was easy to measure the podcast’s reach, and the segments were downloaded in over 10 countries. “It was done on a small scale, from a small publication, and it still had a great impact.”

Jornal de Toronto knows its audience, says Schuster. “From the very beginning, we were worried about creating something well done for a qualified audience. We made it a perfect match for the current immigrant,” Schuster says. “I’m proud to show on my LinkedIn that Brazilians in Canada have a good newspaper, right? That’s not just for talk of culinary recipes, or horoscopes.”

“There are more Brazilian local media than Brazilian local businesses. The calculation doesn’t add up. The government needs to intervene”

Ramos, with his 14–year experience directing his publishing house Zouk Books, and the house’s three bookstores and its coffee shop, all in Porto Alegre, was set on creating a physical and cultural space for his community here in Toronto. All his life, as an art curator and educator, he opened spaces focused on highlighting great works of art and culture. At 17, when living in São Paulo, he opened a small, makeshift gallery to teach and exhibit art pieces. Since then, he’s had cultural spaces in São Paulo, Porto Alegre, and, finally, in Toronto, with Jornal de Toronto.

On March 4, 2020, Ramos got the keys to the building that would host News&Arts, Jornal de Toronto’s second physical cultural space. On March 17, 2020, the Ontario government announced a state of emergency and News&Arts never got its launch. Ramos was then forced to adapt. The space, a long, rectangular room with an L-shaped main area, a podcast studio, and a small kitchen, was meant to be a place for anyone who enjoyed the arts to gather. It was partly born out of necessity for Jornal de Toronto’s team to meet in person, but would also serve as an area for workshops, talks, exhibitions, and roundtable discussions.

During the strictest periods of lockdown in Toronto, Ramos used the space sparingly for team meetings and podcast episode recordings. The podcast studio had two rooms, divided by a glass window, which lent itself perfectly to the restrictions of the COVID-19 pandemic. The host and guests could see each other as they talked in person while still being socially distanced. For the periods when lockdown restrictions were looser, some events did take place, but the space never reached its full potential. “We were all happy to be there doing it,” says Ramos, “but we all knew it wasn’t going to be sustainable.”

What once was a promising project, full of potential, started dying out. In the pandemic early days, they also had to stop printing—in part, to not encourage people to go out and get physical newspapers. The last print issue came out on March 1, 2020. Since then, it has been fully digital, with fewer advertisements, fewer resources, and a completely volunteer-based workforce: they can’t afford to pay their writers anymore. “The following issue—April’s—was almost ready,” says Ramos. “But it never went to print.”

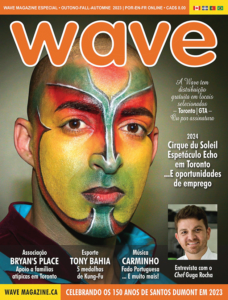

Other Brazilian media organizations were affected. “COVID-19 changed everything,” says Teresa Botelho, cofounder of Wave, a Brazilian magazine based in Toronto. The role of a print magazine has changed, she says, as it cannot compete with the speed of social media. Wave used to have a good reach in local Brazilian, Portuguese, and Latin American businesses around the city. But Botelho noticed that with the pandemic, many either closed down or shrank in size. There’s no longer, physically, a place for magazines.

Wave is one of the oldest Brazilian publications that’s still around. It was founded by Botelho and a business partner in 2003. For a while, it was called Sotaque Brasileiro, which then turned into Brazilian Wave, in a push for a broader audience, and now, just Wave. The magazine is still being printed, seasonally, and it is delivered for free to a small list of subscribers.

Ramos believes the pandemic changed the way audiences consume content. Ideally, he wouldn’t depend on social media. For him, it’s hard to gauge how much a post’s “Like” feature means something was actually read. Unfortunately, social media has made a major impact on how people get to Jornal de Toronto’s content. Considering his simple goal of educating his community and a lack of dependence on social media, Ramos didn’t seem too worried about the impact of Bill C-18 on its online presence. He says, “It’s more important to have readers than Likes.”

Still, the Meta block has reduced the number of people accessing Jornal de Toronto’s content on Facebook and Instagram. And with the lack of advertising, money, and reach on social media, Ramos thinks the community is missing out “immensely.” Ethnic publications can only do so much with the limited resources they have. It’s rare, for example, for them to print frequently—daily or weekly—like bigger newspapers or magazines. Jornal de Toronto’s print editions came out monthly, while Wave follows a seasonal schedule, printing four to five times a year. Some Portuguese papers, with more resources, are published weekly. But still, “there is a big gap here,” says Schuster, and they can’t compete with the mainstream media.

The pandemic has also affected Jornal de Toronto’s team psychologically. Toronto is an expensive city to begin with and the pandemic has affected motivation. “Everyone is a lot more discouraged,” says Ramos. The original goal was to “create a cool project—something that would help the Brazilian community here,” he says. It’s still cool, he says, “but not as good. To me, it’s not really fun anymore.”

It’s been a good run for Ramos, but now he can’t afford to print—no one can, really—and he can’t afford to pay his writers. It seems the community is losing its voice in the media. “There are more Brazilian local media than Brazilian local businesses,” says Schuster. “The calculation doesn’t add up.” Schuster says the government needs to intervene. Local community papers need to be, in some way, subsidized by the government. “They are important, but in today’s market, they don’t have the resources to support themselves.” Immigrants need to see themselves. If they are represented in a strong local media, they will have a better chance at getting into mainstream media, he says. “If the government invested in local community papers,” says Schuster, “there would be so much more interesting content.”

Jornal de Toronto manages to maintain itself as a quality publication, even online. During the pandemic, its virtual readership grew immensely. But success online doesn’t support it financially. Most of the people, if not all, at this point, behind the Brazilian community papers work as volunteers. “The volunteers work as much as they can. They do their best,” says Schuster. But, as he points out, there’s a lot that they can’t do without money.

Schuster himself still works for Jornal de Toronto on a volunteer basis. He writes a monthly column, for free. “It’s the only way I have not to shelve my diploma,” he says. “If I didn’t have that, I’d be depressed.”

About the author

Mariana Schuetze is a fourth-year undergraduate journalism student at Toronto Metropolitan University. She is the Editor-in-Chief of CanCulture Magazine and works at TMU’s radio station, Met Radio as the Collective Coordinator – so she spends most of her time looking over other people’s work and replying to emails. In her work, she loves to talk about arts, culture and their importance to society.