After years of being exposed to trauma, these journalists are advocating for better mental health support

On a dark autumn day in 2010, Dave Seglins sat through a court hearing in Belleville, Ontario, that would change his life. It was there that Colonel Russell Williams, a formerly esteemed commander of the Canadian Forces, pleaded guilty to two murders, two sexual assaults, and 82 break-ins and attempted break-ins. Williams had taken photographs documenting his sexual crimes, including the injuries he inflicted upon his victims. Seglins, a reporter of 25 years, watched in horror as these pictures were revealed in the courtroom. “I sat through the court proceedings and I got out the other side and developed PTSD,” he says. “It was terrifying for me because I didn’t know what was happening to me. I was having horrible thoughts. I couldn’t get the images out of my head.”

Seglins later learned that disturbing images like the ones he saw can cause vicarious secondary trauma in observers. Despite having just been a witness to this terrible case, he was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder. However, what was missing in this situation was enough support from CBC News, Seglins’s workplace. “I felt very alone,” he says. “My employer has actually never asked me, even to this day, about that horrible experience.”

Many journalists dedicate their careers to covering murder, sexual assault, war, and other tragedies and can experience symptoms of trauma due to repeated exposure or even after just witnessing one such event. In May 2022, the Canadian Journalism Forum released the Taking Care Report, which Seglins worked on with Carleton University assistant professor Matthew Pearson. Through their research, they found that journalists have higher rates of anxiety, depression, and trauma than the Canadian averages. They also found that many workers don’t know where to turn when they encounter these emotions: open discussions around mental health are still relatively recent in the industry, and very few Canadian newsrooms offer any training or education on how writers, photographers, and other news professionals can protect themselves while covering a difficult story.

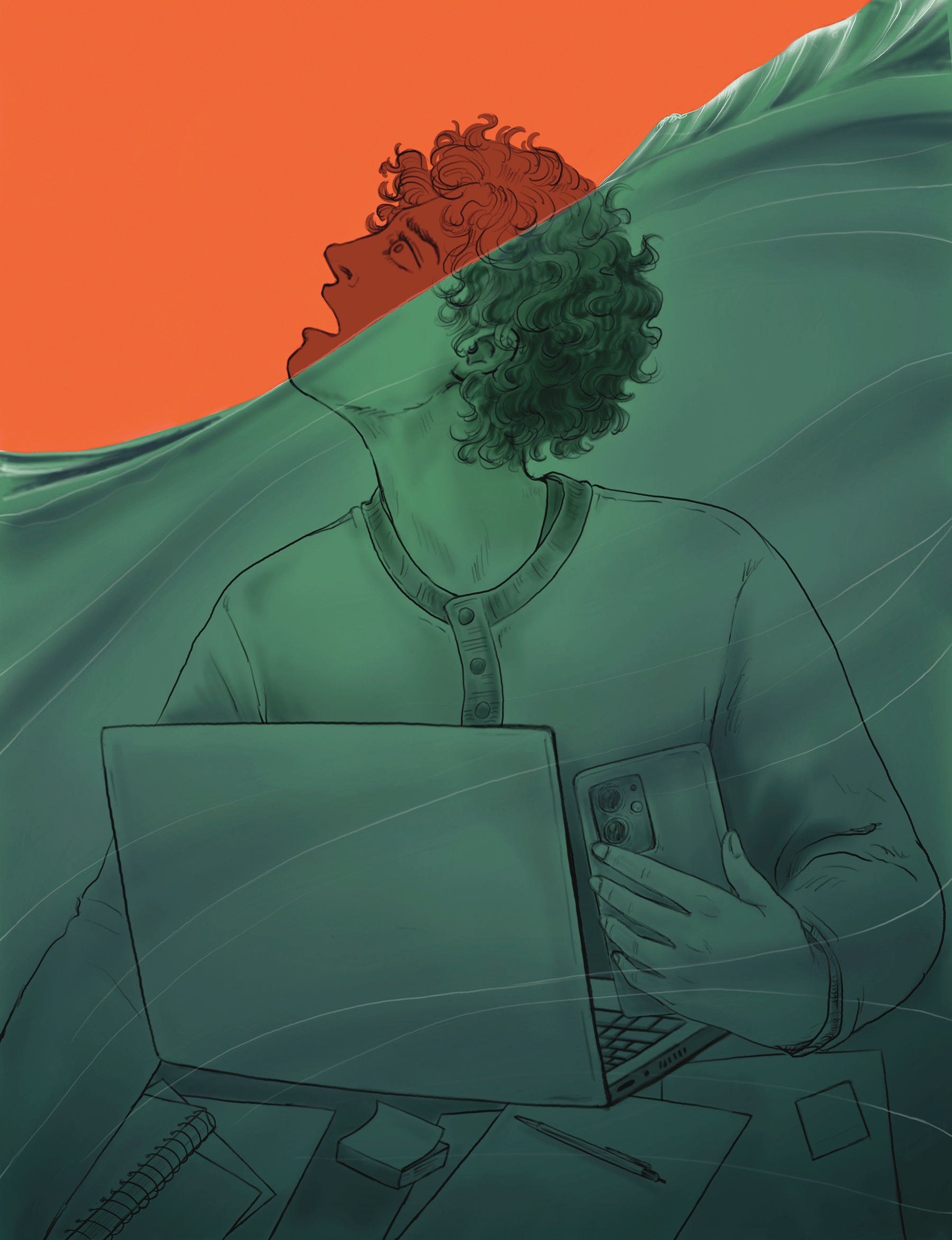

As a result, the Taking Care Report called on Canadian media organizations, including journalism schools, to better support and educate their staff and students—a task that is becoming more urgent as social media and new technologies make it easier to access traumatic images and stories at any time. If newsrooms do nothing, their journalists may face long-term symptoms of PTSD, leaving them with emotional and physical symptoms that can make it incredibly difficult to do their jobs.

Learning about trauma and how to support journalists facing trauma is an ongoing struggle. In 2020, Tamara Cherry, a Regina-based journalist who worked in Toronto for nearly 15 years, launched her company, Pickup Communications, where she provides support for trauma survivors and helps them share their stories. “If you asked me five years ago, I would say there’s nothing more I could possibly learn about trauma. I know everything there is to possibly know. I report on it all the time,” Cherry says. “But if you ask me today, I would say that the more I learn about trauma, the more I realize what I have left to learn.” She believes that, like her, newsrooms can always expand their knowledge of trauma and trauma survivors. She thinks this expansion also applies to journalism schools, which should be making trauma reporting part of the curriculum.

Cherry, who published her book, The Trauma Beat: A Case for Re-Thinking the Business of Bad News, in 2023, says that there are many different forms of trauma exposure that journalists must deal with on a daily basis, from observing other people’s grief to sitting in a courtroom where graphic images are shown as evidence. With surveillance footage and cell phone footage becoming more common, journalists can see the moment of someone’s death or an attack. Many sift through graphic imagery that has not yet been vetted or edited for the general public. Journalists are constantly being exposed to traumatic events in all kinds of different ways. The Taking Care Report also found that media workers who spent a lot of time reviewing disturbing images or details, such as video journalists, camera operators, podcasters, video editors and librarians, and researchers are most affected. Others are traumatized by the abuse they receive for their work.

A few months after reporting on a British expat in Pakistan who had been arrested under blasphemy charges and faced religious persecution, Saba Eitizaz received a letter with a photo from a woman. Upon opening the letter, Eitizaz found a photo of the man she had reported on back home with his grandchildren. Eitizaz laughed joyfully as she recalled this moment that reminded her of the meaningful impact her work has on people and their families. “Usually those cases never even make it to court. The religious mob creates such anger and fervour that the person who has been accused of such a thing gets killed even before getting to court,” she says. But through her coverage, this man was repatriated back to the U.K. Despite experiencing traumatic situations, Eitizaz chooses to do this for the justice she brings to many innocent people.

Eitizaz is the current cohost and producer of the Toronto Star’s podcast This Matters, and a multimedia journalist with almost 17 years’ experience as an international correspondent. She has dealt with religious persecution and online abuse and hate. However, her work on human rights violations in Pakistan put her in serious danger and ultimately led to her exile from the country.

Despite Eitizaz’s move to Canada, her exposure to trauma has not changed. “Especially since the pandemic, there has been so much hateful rhetoric against minorities, against journalists,” she says. Being a Muslim and a female journalist in Canada, Eitizaz has dealt with a constant stream of hateful comments and death threats.

Due to the prolonged periods of digital abuse and the trauma of covering horrifying stories, Eitizaz was diagnosed with complex PTSD. While PTSD tends to occur after a single incident, complex PTSD is typically the result of continued exposure to traumatic events over months or years. “There have been times when I physically haven’t been able to work,” she says. “I’ve had to take medical leave.” Having to deal with these symptoms, such as recurring distressing thoughts, is not an easy task. “You’re carrying your own burden and your own mental and emotional toll of the constant and relentless hate that you’re facing,” says Eitizaz. The Taking Care Report found that Arab, Asian, and Black media workers have the highest rates of harassment and violence within the workplace, as well as from the general public.

How do journalists move forward after all the trauma they’ve been exposed to? Cherry mentions an example a fellow journalist once shared with her: “His therapist referred to the brain as a parking lot and said you can only park those traumatic memories back in the boonies for so long before the boonies start to overflow and you have to start dealing with them.” However, therapy is not always accessible and journalists without benefits, especially those who do freelance work, are often unable to receive help from their employers. For those who do not have access to those benefits, Seglins suggests speaking with a family doctor, who can recommend accessible counselling, or looking into the Trauma Assistance Fund for Freelancers, available through the Canadian Journalism Forum on Violence and Trauma.

Despite the changes that need to made in newsrooms, it’s important that journalists remember how meaningful their jobs are

Both Seglins and Cherry suggest talking about the stories with family, friends, and colleagues, and recognizing that the experiences are more common than one might think. “When you’re telling a story, you’ve become a part of that story. So it should be okay for journalists to feel like they can talk about the hate, harassment, and abuse they receive,” explains Eitizaz. It is in these moments that we need to know that we can lean on our community and loved ones for support.

Is it possible to change attitudes that have been present in journalism for so long? Seglins believes it’s important to start at the very beginning. “It’s time that journalism schools very intentionally talk about the psychological risks of doing this job,” he says. Journalism schools are a great place to start in teaching the new generations of journalists how to better support themselves and each other. Luckily, this has started to become more prevalent in recent years.

But while the younger generation of journalists seems to be more open in the discussion of trauma and mental health, the path forward doesn’t stop there. Seglins says there is a need to direct this discussion toward older generations of journalists, who need to become better versed in mental health and trauma awareness. “There’s an entire generation of leaders who’ve never thought about this, and they tend to be the ones who are actually running the shops,” he says. “Newsrooms have the power to change the protocols around assignments and it starts with a very simple thing, which is asking people, ‘How do you feel about covering this story?’” Journalists’ feelings and personal experiences should always be considered in the newsroom prior to an assignment, giving them control and an option to say no, Seglins argues.

Eitizaz believes that newsrooms need to keep in mind that journalists are coming from all kinds of backgrounds. “We obviously need more representation and diversity at executive and management levels, as well for people to be able to understand that,” she says. There are many situations that may not affect one journalist but can deeply injure another, and newsrooms need to consider this. “Don’t expect journalists to continue to work through their trauma because that’s how it’s always been done,” says Eitizaz.

Luckily, journalists like Seglins are fighting for change. Until two years ago, the job of a well-being champion had never existed, and Seglins was the one to propose it and be the first to take that role at CBC News. He first came to the idea of this role a few years ago, after an argument with his bosses about his own experiences with trauma and PTSD. After Seglins’s request to be taken off an assignment dealing with a particularly gruesome story was rejected, he fought for the need to better support journalists’ mental health. He was ultimately given a chance to research and create a role that would help improve this in their newsroom. “I pitched to my bosses the creation of a new job, ‘journalist and well-being champion,’ to work full time on training, implementing new mental health protocols in the newsroom, and developing best practices across CBC when it comes to covering and mitigating the risks of trauma heavy assignments,” he says.

Despite the changes that need to be made in newsrooms, it’s always important for journalists to remember how meaningful their jobs are. Having spoken to many journalists in his career, the main takeaway for Seglins is always that they love what they do despite how hard it can get. “We are front-row witnesses to some of the world’s most amazing events. The most unique things in human experience and in telling stories, even of trauma survivors—we are empowering them and giving them voice,” he says. Being a journalist is an amazing job and we as journalists need to support each other in order to get through the negative things we face. “Know that we do this with purpose.”

About the author

Lauryn Kovacs is a fourth-year undergraduate journalism student at Toronto Metropolitan University. Her interests include singing, songwriting and making illustrations. When she is not writing she is napping whenever possible.