There’s undeniable value in publishing personal experiences about race—but could it harm my career?

Back in December, I shared a personal experience of a microaggression in an episode of We Met U When . . . , a documentary podcast series that explores the power of news stories and the experiences of the people in them. I recorded this experience unexpectedly while wrapping up a phone interview with a professor about a Black scholar she mentored. She brought up my Korean background and proceeded to lecture me about my use of “able to.” The professor said one of her Korean students had also been making that “mistake.”

My team and I decided to publish this tape because it serves the public interest: it’s a clear example of microaggression, which research shows has been misunderstood by the general public, and even within the scientific community. By sharing it, we hope to show the harm it causes.

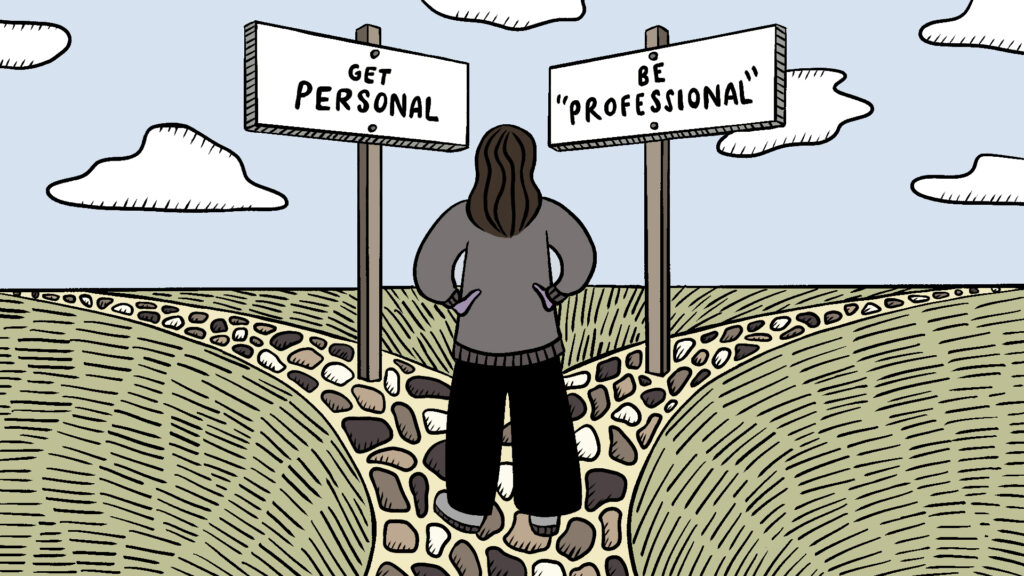

Producing this project felt worthwhile, though I worry about how listeners may perceive it—especially potential employers and coworkers in the journalism industry. As an early-career journalist, I’m concerned about how using my personal experience to address a race-related issue will affect my credibility.

Although awareness of systemic racism increased in Canada during the pandemic, I’m choosing to speak out at a time when some high-profile Canadians are trying to downplay its effects. Just last month, Conservative Party leader Pierre Poilievre said in a viral interview that he wants to put aside “this obsession with race,” blaming what he called “wokeism” for its resurgence.

While my concerns as a Korean Canadian journalist may not exactly mirror those of Black, Indigenous, or other racialized groups in Canada, they do reflect the broader challenges racialized professionals face. Since sharing my experience, I’ve been thinking about what kind of mark it will leave on my professional reputation.

Navigating White-Dominated Newsrooms

In 2024, 75 percent of journalists and 83.4 percent of supervisors in newsrooms across Canada were white, according to the diversity survey results released by the Canadian Association of Journalists last month. An increasing number of racialized journalists who’ve worked in predominantly white newsrooms have shared publicly that they’ve felt unsupported when raising issues of race or covering their own communities. Sunny Dhillon, who left The Globe and Mail in 2018, likened being a journalist of colour to “walking a tightrope” in an interview with CBC’s As It Happens. Angela Sterritt said in a 2023 interview with The Tyee that “your sense of belonging in the newsroom” is “chipped away at all the time” when you’re a person of colour reporting on your own community.

Revelations like these caught the attention of Hadiya Roderique, an assistant professor of journalism at the University of Toronto Scarborough. They prompted her research on a new project that will explore how journalistic objectivity may be weaponized against racialized journalists as they navigate newsroom politics.

Roderique’s research is informed by the people she works with as a lawyer and writer. Her viral 2017 essay Black on Bay Street in The Globe and Mail explored the challenges she faced as a Black professional. She recalls a superficial kind of acceptance in the field of law: “It felt like they wanted Black white people, people who conformed to everything on Bay Street but just happened to have brown skin.” Her research reinforces my concerns about how racialized journalists are perceived when addressing issues of race, especially in predominantly white newsrooms.

The Value, The Challenges

Despite my concerns, it remains valuable for racialized journalists to share their personal experiences with race. Their perspectives can help address the underrepresentation and misunderstanding of race-related issues. For instance, journalist and author Eternity Martis wasn’t seeing Black student representation in the media when many were experiencing racism on predominantly white campuses. Discussing her own experience as a woman of colour on a Canadian university campus in her 2020 memoir, They Said This Would Be Fun, allowed her to represent what she wasn’t seeing.

Talking about personal perspectives on one’s race can also feel timely. Nicholas Hune-Brown, journalist and now executive editor at The Local, included his mixed-race identity in his 2013 piece, “Mixie-Me: A Mixed-Race Generation Is Transforming the City,” for this reason—despite thinking twice about writing the piece. He gave in when he realized he could explore the idea of post-raciality in the midst of a Black presidency across the border.

Additionally, sharing personal stories about race can come with navigating the vulnerability of publicizing information that is typically private. Martis was aware of this challenge as she wrote about her experiences. “I sacrificed a bit of my own privacy because the story I needed to tell felt so much bigger and stronger,” she says.

It also comes with submitting to the possibility that the evolving conversation around race may make earlier reflections feel outdated. Hune-Brown has seen the discourse around race evolve and feels that there have been more nuanced conversations since he wrote his piece, admitting, “I would frame it a bit differently if I were doing it today.”

The Case for Caution

If racialized journalists want to discuss personal experiences with race in their stories, Martis and Hune-Brown believe they should do so with caution. For Martis, setting boundaries was key to her writing process. While writing, she often asked herself: “If someone Googled me and my book came up, would I feel comfortable, and would I be able to stand by what I wrote?” This meant trimming the fat from her stories and keeping some details for herself. “I had to make decisions about boundaries,” she says, “in order to share that story and feel comfortable with it.”

For Hune-Brown, caution also means being wary of being pigeonholed. He is conscious of this as an editor and would encourage young writers—particularly racialized ones—to be cautious about being boxed into writing exclusively about race. “Young writers,” he says, “are right to be a bit wary about selling only their personal experiences of race.” He advises them to develop strong pitching skills on a variety of topics so they’re not limited to a narrow, identity-based niche.

Writing much of this piece in the first person is my way of acknowledging my place, and examining the implications of journalists getting personal about race. I’m not separate from this issue as I report on it.

By sharing my own experience and learning from other racialized journalists who have shared theirs, I’ve come to see both the value and the challenges of telling personal stories about race. These stories can shed light on experiences that are often overlooked, or misunderstood. But telling them also comes with burdens that racialized journalists carry throughout their careers.

I hope the industry evolves to better support racialized journalists so they can tell these stories without fear of backlash or pigeonholing in their careers. Until then, I’ll continue to share with care—and caution.

About the author

Chloe is in her final year of the Master of Journalism program and works on the Review’s senior editorial team. She is interested in audio-based journalism and stories that prioritize underrepresented voices. She’s interned at The Big Story Podcast and CBC’s Day 6.