Lessons from the Ottawa trucker protests

Mike LaPointe darts back in from the cold, flexing his fingers to warm them up as he sits down to write. One hour inside, then back out to report some more. He pens just 100 words, then goes back to covering the story occupying the heart of Ottawa—the trucker protests.

DO identify yourself as media to those you speak to.

This is a basic tenet of responsible journalism, since sources have a right to know who they’re speaking to. A press pass is a useful way of providing identification both to sources and to local law enforcement.

DON’T openly wear press credentials.

While it’s critical to have identification on your person, it might not always be wise to display it openly. According to LaPointe, an “anti-mainstream media tenor” was pervasive at the Ottawa protests. Many journalists who were easily identifiable as such (whether that be through openly displayed credentials or obvious camera equipment) faced harassment from the crowd. This might not be the case at every protest, but it’s smarter to take out credentials to show to specific individuals instead of risking your personal safety by displaying them openly.

A large number of protestors gather and form a circle around Isaac Phan Nay as he is doing an interview with one of them. As the group closes in, Nay begins to feel unsafe, cuts the conversation short and walks away. As news editor at Carleton University’s independent news publication, The Charlatan, Nay is here to cover the protests. But despite the always-looming spectre of impending deadlines, he will walk away from an interview when he starts to feel uneasy. “Don’t be afraid to get out of there,” he says, if you feel your safety is compromised.

DO bring a buddy.

Nay worked alongside co-workers from The Charlatan. “We stayed in almost constant communication with each other,” says Nay. “This protest was especially distrustful of the media, so having a buddy with you is helpful. They can pull you out of situations, there’s another pair of eyes on you, especially when you’re focused on whatever it is you’re reporting on.” His team also had a strategy for various outcomes, including if they got separated; they had decided on a location where they would meet up at the end of the day.

DON’T go off on your own.

While having a plan for if you get separated is key, it’s best to avoid it in the first place. According to Spencer Colby, Nay’s coworker and photo editor at The Charlatan, such a practice ensures a journalist’s personal safety. “If you’re out there doing work with a reporter, stick together, within like a stone’s throw distance so you can easily help each other and bail each other out in case of any unsafe scenarios,” he says.

Justin Ling knows he has to use a bit of charm when talking with the police. The Montreal-based freelance reporter journeyed across the river to cover the Ottawa protests, and knows you often catch more flies with honey than with vinegar.

DO interact politely and respectfully with local law enforcement.

“When you’re dealing with officers who are just trying to keep the perimeter intact, a bit of friendliness goes a long way,” says Ling. While journalists should rarely take anything at face value when writing their stories, a cordial relationship with local law enforcement helps with staying safe when on the ground.

DON’T expect them to answer questions.

“There’s not much use in going up to a police line and talking to a guy in full riot gear to ask him a bunch of questions,” says Ling. “He’s there in a very tense situation. He does not want you talking to him, and you’re not gonna get anything terribly useful anyway.”. Police can sometimes have outreach or crowd management officers who can be more helpful, but Ling describes these as a “rarity.”

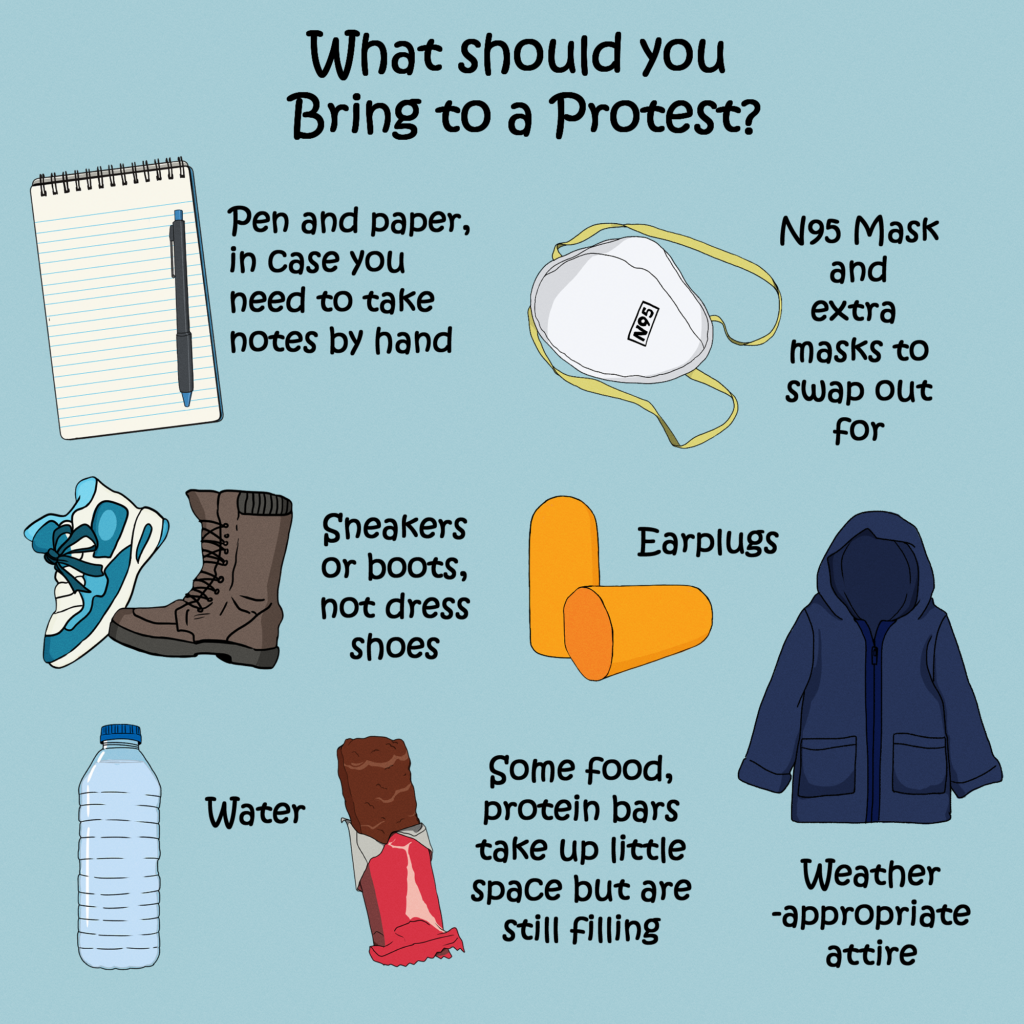

DO prepare.

While they gave differing advice on certain topics, Ling, Colby, Nay, and LaPointe all agreed on how important it was for journalists to prepare before going to a protest.

“It’s almost important to over prepare,” says LaPointe, before continuing on: “You have to know your surroundings, you have to know what you’re getting into, you always have to have a safe place to go if things get out of hand. It helps to go in groups … and you have to go in with an open mind.”

It’s one of the last things LaPointe says in our interview that sums up why preparation is key, not just for journalists but for their readers: “These are very important stories. This is a very important time in history. And it’s a bit of a privilege to be able to tell that story to the readers and to the rest of the world.”

About the author

Alexander Sowa

Alex Sowa is Copy Editor at the Review of Journalism.