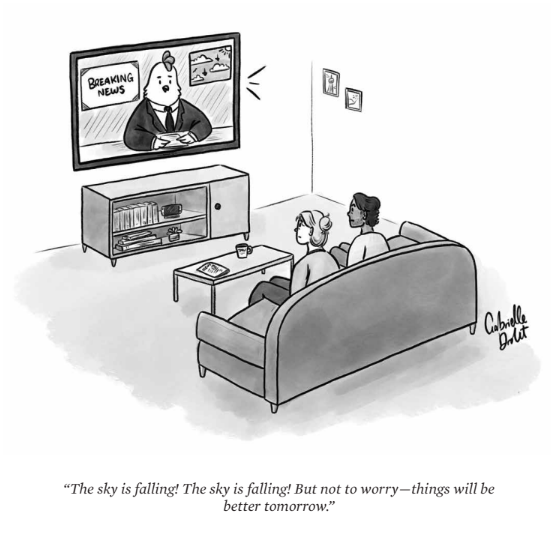

Audiences are sick of bad news. Can a rising tide of optimistic news outlets fight compassion fatigue?

Cartoon by Gabrielle Drolet

When former CNN and ABC war zone correspondent Muhammad Lila realized he had become the person on TV who told people how bad the world was, it made him curious. Why, he wondered, was the news always bad? Eventually, he decided it was time to make a change—for himself and for his audience. “I spent about 10 years of my life on the frontlines of the world’s biggest conflicts,” he says. “Averaged more than 100 flights a year—been shot at, held at gunpoint, survived explosions, flown on aircraft carriers, had threats directed against me.”

Then an event sparked a second epiphany. On March 15, 2019, a 28-year-old Australian man opened fire in two Christchurch, New Zealand, mosques, leaving 51 dead and 40 injured. Recalling the gunman, Lila wondered, “What would happen if, as he was thinking of walking out of his home and he had the rifle and he had his ammunition and the body armour, if you could tap him on the shoulder and say, ‘Hey, sir, I just want you to know that there’s a mosque down the street and they’ve been feeding homeless people for the last month. Or they’ve been contributing to the community in a way that perhaps you didn’t know.’ What would happen if you could intervene in that way and show him something good that that community had done? It may not get him to stop hating that community, but it might just be enough for him to say, ‘I’m not going to walk in a mosque and shoot people today because I saw a side of them that I wasn’t exposed to before.’” One year later, Lila founded Goodable, a news platform dedicated to reporting and sharing positive news. He recognized the potential of showcasing the good things that happen in the world—he thought it might change perspectives, maybe even save lives, by possibly preventing similar mass shootings. “I realized that I wanted to spend the rest of my life showing people how good the world can be.”

Based on his working experience, Lila sees a relationship between the amount of bad news audiences are exposed to and widespread anxiety, depression, and chronic stress. For him, the current trend toward overwhelmingly negative news bears some responsibility for that. “For the longest time [journalists] thought, Let’s show people how bad we can be as human beings. Let’s show the war, the famine, corruption, the politicians,” he says.

Data published last year by the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism appear to validate Lila’s views. Reuters’s Digital News Report found that the proportion of news consumers who avoid the news has increased noticeably since 2017, with approximately one-third of respondents indicating that news has a negative effect on their mood. In general, interest in television and print news has significantly decreased across the Americas, Europe, Asia-Pacific, and Africa, from 63 percent in 2017 to 51 percent in 2022. Meanwhile, online news consumption on smartphones or via Facebook, TikTok, Twitter has not made up the gap. In other words, consumers may be experiencing compassion fatigue or apathy regarding the human tragedy reported in the media. And when readers turn away from the news, media outlets suffer financially.

Relieving compassion fatigue could be one remedy for a struggling news industry. But how media outlets reconnect with and convince audiences that paying attention to news is worthwhile is not yet clear. With its focus on offering audiences greater empowerment, improved mental health, agency, empathy, humanity, and connection to one another, Goodable—and other forms of “good news” journalism that have arisen in the past decade—could provide an answer. “If journalism, at its best, is like holding up a mirror to society and saying, ‘This is who we are,’ why are we only showing the hideous aspects of human nature?” asks Lila. “Why aren’t we showing the positive, compassionate, healthy, happy, amazing side of human nature?”

A Brief History of Bad News

Compassion fatigue, defined by Collins English Dictionary as “the inability to react sympathetically to a crisis, disaster, etc., because of overexposure to previous crises, disasters,” emerged as a media concept in the 1990s. Susan Moeller, a former journalist who now teaches media and international affairs at the University of Maryland, wrote in her 1998 book Compassion Fatigue: How the Media Sell Disease, Famine, War and Death, “It seems as if the media careen from one trauma to another, in a breathless tour of poverty, disease and death.” By Moeller’s account, compassion fatigue is a vicious cycle. “When war and famine are constant, they become boring.” Or worse: research by Keith Payne and Daryl Cameron at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill found that the more victims people see being hurt or killed, the more they shut down their emotions.

The media play a massive role in all of this. The Pew Research Center’s 1995 study “International News Coverage Fits Public’s Ameri-Centric Mood,” found that “[F]oreign events and disasters usually must be more dramatic and violent to compete successfully against national news.” American media theorist Neil Postman, in his 1985 book Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business, claimed that television had the power to turn news into entertainment. Being part of the entertainment industry, he argued, the media must captivate their audience no matter what, as they largely pay their way by peddling advertising, as opposed to selling news. So, they must appeal to the largest audience, with attractive demographics for advertisers, and the best way to do that is by covering shocking affairs that make the world more fascinating. Or so it once seemed.

Solutions Journalism and Good News as an Answer

Individuals today may experience compassion fatigue simply by consuming news. In a 2018 essay for The Guardian, poet Elisa Gabbert noted that any political, social, and/or economic difference a single person can make may seem tiny—and enough to make us question the utility of news for consumers.

University of Victoria’s Sean Holman believes there is a way out of this pit. The associate professor looks at news as servicing two desires among members of the public: control and certainty. At a time when democratic systems around the world are breaking down, the media offer information that can be used in decisions that shape public and private institutions. “With information,” he says, “we can feel more certain about the world around us, better understanding the past and present and better anticipating the future.”

But the information must make it to the audience first. To do that, says Holman, the focus should be on sharing our experiences with one another. “We want to cherish the people that we care about. We want to cherish the people who are part of our community. That is a fundamental human desire, and that is a desire that’s been with us since humanity first walked this earth. So, what we’re really talking about here is how do we create compassion communities?”

One way to go about this, Holman suggests, is to bring large-scale problems down to an individual level. He offers homelessness as an example. “If we treat these problems as a summation of a whole bunch of individual problems, maybe the world’s big problems will seem less like mountains than a collection of molehills. You have to give audiences avenues of empowerment.”

“I realized I wanted to spend the rest of my life showing people how good the world can be” – Muhammad Lila

In the late 1990s, a different type of journalism emerged that began to consider the efforts being made to solve social problems. Solutions journalism, as it is now known, reengages audiences in the process. It explains how and why responses are working, or not working, and attempts to present people with a more authentic and complete view of issues, allowing them greater agency over their lives.

One of the best examples of this approach to reporting is the nonprofit Solutions Journalism Network, founded in 2013 by journalists David Bornstein, Courtney E. Martin, and Tina Rosenberg. The SJN website includes a Solutions Story Tracker, a searchable database of stories that exemplify “rigorous reporting on responses to social problems….an inspiring and useful collection of the thousands of ways people are working to solve problems around the world.” Journalists are also directed to resources on how they can advance their reporting and increase audience engagement through solutions journalism. In addition, SJN has partnered with Google to help spread solutions-based stories even further. Now, if a user asks Google Home or Google Assistant, “Tell me something good,” Google shares a summary of a positive news story, curated by the SJN team. According to Google, this reorientation includes news such as how Georgia State University “coupled empathy with data” to narrow academic gaps between white and Black students; how East Detroit beekeepers saved their dying bee population, thus contributing monies to their local community; and how Iceland used curfews and extracurricular activities to help limit teen drinking.

Solutions journalism aims to make a tangible difference. Mikhael Simmonds, who until last year managed new relationships at SJN, points to a solutions story published in The Plain Dealer, a Cleveland-based newspaper. The 2015 article “How Rochester Responded to Its Lead Poisoning Problem: Toxic Neglect” evaluated approaches to reducing lead poisoning in children and pointed to the model in Rochester, New York, to suggest best practices for other cities to follow. “Solutions journalism becomes like pollinators of good ideas,” says Simmonds. “So, if a problem is happening in one community, they could say, ‘Hey, we could learn from somewhere else in another city, another time, another place.’”

Putting People First

Another way journalism may be changing its focus for the better is by including the perspectives of communities that have long been shut out of representations of the injustices they face. Solidarity journalism, with its commitment to social justice being translated into action, is one way to focus on individual stories. Anita Varma, an assistant professor in the School of Journalism and Media at the University of Texas at Austin, says, “With solidarity journalism, that action is actually the action of reporting. So, reporting on issues where people’s basic dignity is at stake.” Varma cites a 2022 article in The Washington Post, “Inflation Is Making Homelessness Worse,” as an example. “I thought they did a phenomenal job reporting on how expensive the cost of living has become in the United States with inflation,” she says. “We see that happening worldwide, but so much of that coverage has only quoted an economist, the Fed chair [Jerome Powell], the president, maybe a senator. What the Post does differently is they spoke to people who made $100,000 last year and this year cannot pay their rent.”

The impact of such stories, Varma says, is that “there’s a conceptual notion that if people are aware of ways to stand together, I would feel less exhausted.” She admits that though its impact has not been proven empirically, she is convinced solidarity journalism “absolutely has a chance to bring people back into more civic engagement.”

IndigiNews is a news outlet that aims to produce digital journalism driven by the needs of Indigenous communities, while contributing to the long-term sustainability of independent, Indigenous-focused media. Odette Auger was the managing editor of IndigiNews at the time of reporting (now she’s the managing editor of the Watershed Sentinel). Regarding IndigiNews’s methods of reporting, she says that “by centring people in our stories, it provides an easier access point for readers to delve into issues that need to be discussed.”

Since its inception, IndigiNews has challenged the very concept of what news is as a means of reengaging the Indigenous community. According to Auger, “We’ve been raised here in Canada to filter certain realities out, and it’s done through always centring a predominantly white, male perspective.” For example, Auger says writing about Indigenous communities that do not have access to clean, healthy water is not a negative news story, but rather a truth-telling story. “If communities have to live through that, then the rest of the country has to accept that that’s part of our shared reality as Canadians. They need to listen to those stories.”

In more general terms, IndigiNews stakes out its own methodological turf. “Our team is made up of both storytellers who don’t have a background in traditional journalism and those who do,” its website states. “We intentionally didn’t import newsroom culture into our storytelling lodge, and by doing so we have created something special. As paradoxical as it sounds, we’ve created something new that is also inherently old, since it is rooted in our traditions.”

Moreover, the effect of focusing on people need not always require empirical proof. Muhammad Lila, for example, recalls an instance of Goodable’s ability to connect with its audience. An anonymous woman contacted him through social media and said, “I want you to know that you’re doing so much more than you think you are.” She told him she lived in a neighbourhood where she felt unsafe. Worse, she couldn’t afford to feed her family. One day, she’d had enough and decided to jump off a bridge. “While I was on my way to that bridge—I don’t know how, but somehow I saw Goodable on my phone—a video of an act of kindness.” Lila says that for that woman, it had confirmed that there was good in the world. “I was crying happy tears for the first time in years,” the woman wrote.

Her story illustrates for Lila the potential of Goodable and its approach to focusing on people and good news. “We are impacting people in ways that are treating their anxiety, depression, insomnia, stress, even suicidal ideations,” he says, “because we’re showing people that life is inherently good.”

The Allure of Bad News

Good news journalism sounds great. Yet, it raises the question of whether it minimizes issues or harbours biases that may influence action one way or another, thereby undermining journalism’s key tenets: truth, accuracy, and objectivity.

Another problem is whether good-news stories can compete with people’s attraction to misfortune and tragedy. Research has found that human beings, particularly consumers of major media, show a negativity bias. That is, we like negativity in our stories. If that’s the case, then major media are simply responding to consumer demand.

“Bad news sticks to the brain like Velcro. Good news slides right off like Teflon” – Dr. Rick Hanson

In an interview with Good Good Good, an independent media organization founded in 2017 to create content and resources about the good in the world, psychologist and New York Times best-selling author Dr. Rick Hanson said that “Bad news sticks to the brain like Velcro….And good news slides right off the brain like Teflon.” That is, negativity bias is programmed into us.

Almost naturally, global news cycles focus on negative news stories. In fact, a 2019 study by Stuart Soroka, Patrick Fournier and Lilach Nir, “Cross-national Evidence of a Negativity Bias in Psychophysiological Reactions to News,” published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, addressed this point. The researchers assessed the global demand for negative information in news cycles across 17 countries and found that the average person had stronger physiological reactions to negative news stories than positive ones.

This is reflected in the angles journalists take in their stories. In “Why Is All COVID-19 News Bad News?” Bruce Sacerdote, an economics professor at Dartmouth College, and his colleagues Ranjan Sehgal and Molly Cook analyzed the tone of English-language articles on COVID-19 written since January 1, 2020. Albeit an American example, the findings are telling. The researchers found that 91 percent of stories by major U.S. media outlets were negative, compared to 54 percent of those from non-U.S. sources.

Moreover, the researchers found that “[t]he negativity of the U.S. major media is notable even in areas with positive scientific developments including school reopenings and vaccine trials.” They also wrote that “[s]tories of increasing COVID-19 cases outnumber stories of decreasing cases by a factor of 5.5 even during periods when new cases are declining.” In fact, Sacerdote and his coauthors reported, “Among U.S. major media outlets, stories discussing President Donald Trump and hydroxychloroquine are more numerous than all stories combined that cover companies and individual researchers working on COVID-19 vaccines.”

A Question of Balance

In addition to possibly being less attention-grabbing, the various forms of good news may not actually accomplish what they set out to do. In a 2017 article, “Solutions Journalism: The Effects of Including Solution Information in News Stories about Social Problems,” published in Journalism Practice, Karen McIntyre, an associate professor of multimedia journalism at Virginia Commonwealth University, suggested that “solutions-based journalism might mitigate some harmful effects of negative, conflict-based news, but not necessarily inspire action.” Other critiques include the fact that some issues are not easily solved, or that stories may reflect bias or advocacy or are simply “feel good” stories. As well, in a 2014 article in the Columbia Journalism Review Lene Bech Sillesen charged that these good-news outlets, as well as news organizations that have created specific sections highlighting upbeat news, are often designed to generate advertiser or sponsor revenue and so shouldn’t be called news.

For his part, National Post editor-in-chief Rob Roberts defends traditional reporting, writing in an email, “I don’t think there is public apathy toward tragedy, at least not when it comes to extraordinary events.” In fact, he writes, “social media and other factors have only heightened public interest and concern. Look at the impact of Black Lives Matter and #MeToo. People have been electrified by some of the awful events that inspired those movements.”

Journalist and cameraman Joe Sheffer, who has worked at NBC, Vice, and CNN with Lila, also endorses conventional reporting. “News challenges big issues, injustices—things that are wrong,” he says, “and tries to inform people so that they are corrected. So, by default, it is negative.” Otherwise, Sheffer continues, “You often end up in the realm of propaganda or you end up in the realm of soft news and fluffy stories. Although I would like to see [a shift in the tone of stories toward more positive news], I don’t think that’s a realistic game.”

Then again, just because it’s a good-news story doesn’t mean it’s of a lower quality. Good Good Good says editorial staff are careful to hold themselves to the same high standards as traditional newsrooms. The “About” page on its website reads, “We’re committed to the truth in our writing, making public corrections when we get something wrong, and always clearly communicating when we partner with brands.”

At The Globe and Mail, deputy national editor Rachel Giese thinks a happy medium can be reached if the right measures are taken. “It’s important for journalists to be mindful of the kind of negative news bias that we bring into our newsroom.” Giese offers COVID-19 as an example of what she means by a happy medium: “People need to know what’s happening with COVID, they need to know about ICUs filling up. But I work with my reporters to figure out how we balance these stories with solution stories.”

Such an approach may appeal to the widest audience. In their negativity bias study, Soroka and his coauthors found that “all around the world, the average human is more physiologically activated by negative than by positive news stories. Even so, a great deal of variation exists across individuals. The latter finding is of real significance for newsmakers: Especially in a diversified media environment, news producers should not underestimate the audience for positive news content.” They argued, “[T]here may be reason to reconsider the conventional journalistic wisdom that ‘if it bleeds, it leads.’”

In the end, if solutions journalism comes across as “feel good” stories, says SJN’s Mikhael Simmonds, “What’s wrong with that? What’s wrong with a well-reported story about what’s happening that teaches others how to respond?”

Spreading the Good News

There’s evidence that solutions-based journalism is gaining ground. Solving for Chicago, for example, is a “collaborative of 20 print, digital, and broadcast newsrooms working cooperatively to cover pressing issues facing the public.” The collaborative’s latest project works to better understand the ongoing impacts from COVID, particularly on “essential” workers, and how the pandemic has exacerbated existing inequities and opened potential new solutions.

The pandemic made it clear that certain sectors of Chicago, lacking safety nets, bore the brunt of fatalities, homelessness, and abusive workplaces. Jacqueline Serrato, editor-in-chief of Chicago’s South Side Weekly, an alternative newspaper that’s a member of Solving for Chicago, told localmedia.org in an interview, “It is on us to expose the conditions that existed before COVID and that are set to remain even if COVID was eradicated. Working together as newsrooms to seek accountability, transparency, and solutions to the system’s shortcomings seems like the only logical and responsible next step.”

Solving for Chicago is not alone in its efforts. Similar solutions-based newsroom collectives have emerged elsewhere in the U.S., including the Dallas Media Collaborative and Granite State News Collaborative. The approach is also gaining traction in Canada, where The Narwhal and the Winnipeg Free Press are teaming up, as The Narwhal says, “to help fill a void for in-depth and investigative environmental journalism in Manitoba.” The partnership “marks a new era in the coexistence of and cooperation between digital and legacy news outlets,” Narwhal editor-in-chief Emma Gilchrist has said.

There is no doubt that the various forms of good-news media will continue to evolve, building on journalism that is focused on progress, possibility, and solutions. In a world that feels increasingly uncertain, Muhammad Lila, for one, sees good-news journalism as a way forward, offering the keys to remaining resilient during difficult times. “Our souls, our minds, need hope,” he says. “You can’t just scare people all the time. We need inspiration. Human nature dictates that we need to feel safe where we are.”

In other words, we’re going to need the good with the bad.